Shooting The Stars – The Golden Age of Hollywood Portraiture

Hollywood Portrait Photography came into existence at the beginning of the 20th Century, following the relocation of the film industry from the east coast to Hollywood. These fledgling studios needed to create interest in their motion pictures by promoting the actors who stared in them. From 1910 – 1970, there were six individuals that became the photographers of choice for “shooting the stars,” and each, in their own way (as seen above in George Edward Hurrell’s stunning portrait of Marlene Dietrich), helped define the look of the Golden Age of Motion Pictures and the Hollywood star: Albert Witzel, George Hurrell, Clarence Bull, Ruth Harriet Louise, Milton Greene and Cecil Beaton.

As the New York Times reported on September 6, 1936,

The cinema’s glamour machine that takes waitresses, debutantes, actresses, school-girls and their masculine parallels and by adroit veneering makes of them the dream children of the silver screen… Its product thunders from newspaper and magazine pages, from billboards and theatre lobbies. Its prime purpose is to make the customer go to the ticket window and lay down money. It must give the appearance of genius to very ordinary people. It must conceal physical defects and give the illusion of beauty and personality should none exist. It must restore youth where age has made its rounds. It must give warmth to neutral or rigid features. It is in short, the still department.

The vintage original photographs of these six photographers, originally intended for promotional purposes, are now recognized as important, even significant, works of photograph. These images have come to define the golden age of Hollywood portraiture. Their work appears in museums, in private collections, is the subject of exhibitions and multiple books have been written about them and who they shot. What follows is a description of these photographers and their work.

Albert Walter Witzel (1879-1929)

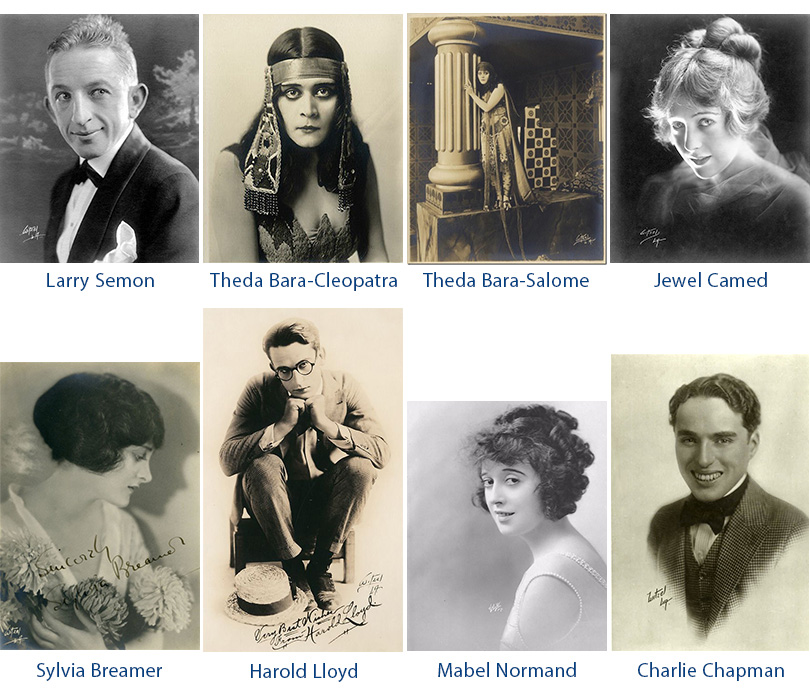

Witzel Studios was founded in Los Angeles in 1909 and within a few years had become one of the city’s foremost portrait studios. With the emergence of the film industry, Albert Witzel was soon in demand from Hollywood studios seeking to create interest in movies by circulating promotional shots of their stars. Distinguished by moody lighting and dramatic poses and settings, Witzel’s photos soon set the tone for Hollywood studio photography where he worked on assignment photographing many silent film luminaries including Theda Bara and Charlie Chaplin. Witzel’s business began to decline in the 1920s, by which time the various movie studios’ relentless publicity machines had resulted in them employing their own teams of photographers. Witzel Studios folded following Albert Witzel’s death in 1929.

George Edward Hurrell (1904-1992)

George Hurrell was the creator of the Hollywood glamour portrait, the maverick artist who captured movie stars of the most exalted era in Hollywood history with bold contrast and seductive poses. However, Hurrell originally studied as a painter with no particular interest in photography, using photography only as a medium for recording his paintings. After moving to Laguna Beach from Chicago in 1925 he met Edward Steichen who encouraged him to pursue photography after seeing some of his works. At about the same time, Hurrell was introduced to the actor Ramon Novarro and agreed to take a series of photographs of him. Novarro was impressed with the results and showed them to the actress Norma Shearer, who was attempting to mold her wholesome image into something more glamorous and sophisticated in an attempt to land the title role in the movie The Divorcee.

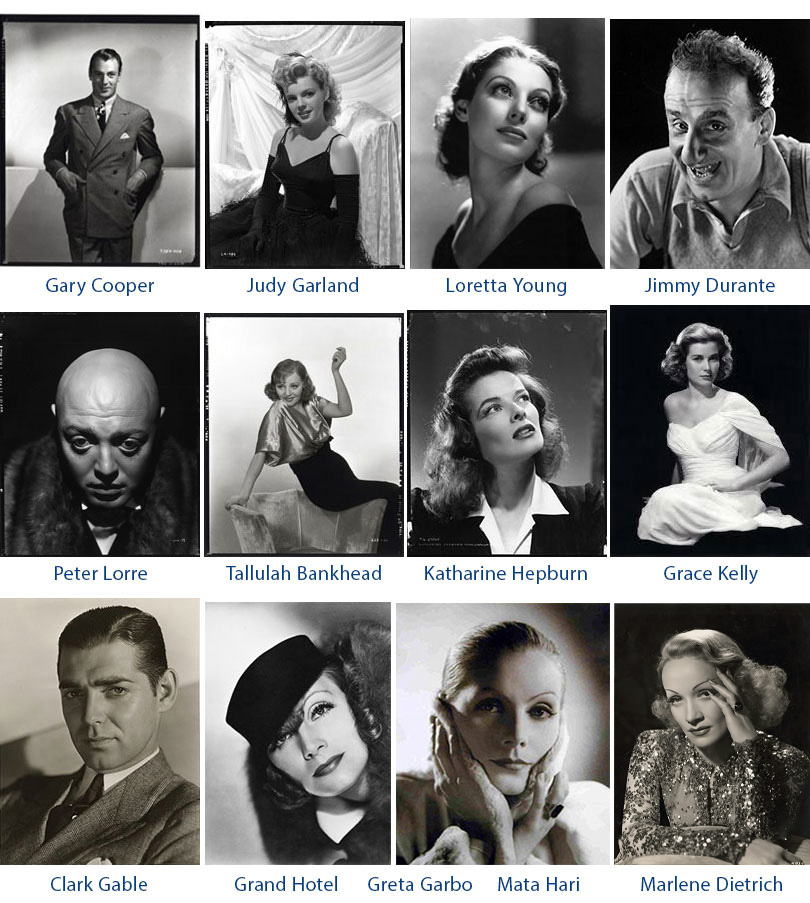

She asked Hurrell to photograph her in poses more provocative than her fans had seen before. After she showed these photographs to her husband, MGM production chief Irving Thalberg, Thalberg was so impressed that he signed Hurrell to a contract with MGM Studios. Hurrell photographed every star contracted to MGM and came to be known as the “Rembrandt of Hollywood.” His striking black-and-white images were used extensively in the marketing of Myrna Loy, Robert Montgomery, Jean Harlow, Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Rosalind Russell, Marion Davies, Jeanette MacDonald, Lupe Velez, Anna May Wong, Carole Lombard and Norma Shearer.

He also photographed Greta Garbo at a session for the movie Romance. The session didn’t go well and she turned to staff photographer, Ruth Harriet Louise, who would go on to help transform a ‘pretty, frizzy-haired’ nobody into the great Greta Garbo. In the early 1940s Hurrell moved to Warner Brothers Studios photographing, among others Bette Davis, Ann Sheridan, Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, Ida Lupino, Alexis Smith, Lauren Bacall, Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney. Later in the decade he moved to Columbia Pictures where his photographs were used to help the studio build the career of Rita Hayworth.

He left Hollywood to make training films for the First Motion Picture Unit of the United States Army Air Forces. When he returned in the mid-1950s his glamour photography had fallen from favor and a more earthy and gritty style had taken its place. He moved to New York and worked for the advertising industry where glamour was still valued. After 1970, his most prominent work was as a photographer for album covers. He shot the cover photos for Cass Elliot’s self-titled album (1972), Tom Waits’ Foreign Affairs(1977), Fleetwood Mac’s Mirage(1982), Queen’s The Works(1984), Midge Ure’s The Gift(1985) and Paul McCartney’s Press to Play(1986). Hurrell died on May 17, 1992, shortly after completing a TBS documentary about his life

Clarence Sinclair Bull (1896-1979)

Clarence Sinclair Bull was one of the great masters of the Hollywood portrait. He, along with George Hurrell, helped create the modern idea of Hollywood Glamour in photography. As head of the stills department at MGM he helped to pioneer the art and craft of the film studio gallery portraitist. These images, once regarded merely as anonymous publicity photographs, have now been re-evaluated for their crucial role in both the creation of cinema iconography and the history of twentieth-century portrait photography. Clarence Bull went to Hollywood in 1918 and became an assistant cameraman for Metro Pictures. During breaks from film production, he began taking photographs of the various stars of the time. Bull’s long association as a photographer with the studio that would become Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer began when producer Samuel Goldwyn hired him in 1919. Managing to survive the commotion of studio consolidation in the early and mid-1920s, Bull found himself at the helm of MGM’s stills department when the studio was formed in 1924, and stayed there until retiring in 1961.

The enormity of MGM’s output of films in the 1920s saw Bull’s domain grow. He was responsible for managing MGM’s staff of photographers and the large support crew of technicians needed to develop, re-touch, print and collate the hundreds of thousands of prints distributed annually by MGM’s publicity department. During the 1920s, even with his administrative duties, Bull continued to take portraits. He photographed many of MGM’s stars including Elizabeth Taylor, Clark Gable, Joan Crawford, Leslie Howard, Katherine Hepburn, Gary Cooper, Hedy Lamarr, Vivian Leigh, Spencer Tracy, Ava Gardner, Grace Kelly, Jean Harlow, John Gilbert and is extremely well known for his numerous photographs of Greta Garbo. Garbo responded to Bull’s quiet professional approach and spent one or two days after completing each film posing in his studio. He estimated that he had taken over 4,000 individual studies of her during their collaboration, which lasted until she retired in 1941. At each session Bull sought to capture the magic, beauty and inner mystery that Garbo projected in her screen roles.

Bull started experimenting with color photography in the late 1930s, making color exposure of Garbo first in 1936 and again in 1941. In the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s he worked extensively in color recording, among others, Elizabeth Taylor at the moment she was being considered for adult roles. Throughout the 1950s Bull acted as an ambassador for MGM by giving celebrity lectures and demonstrations throughout the United States to interested photographic and student groups. However, he continued to take important photographs for some of MGM’s prestige films, including studies of Claire Bloom for The Brothers Karamazov, Leslie Caron for Gigi and Grace Kelly for High Society. Clarence Bull died of a heart attack on June 8, 1979. He lived to see his work re-evaluated in a number of important exhibitions and in his own lifetime witnessed the assimilation of his photographs into the legend of Hollywood.

Ruth Harriet Louise (1903-1940)

Fascinated by photography and having become the assistant to Nickolas Muray, a New York city celebrity photographer, Louise decided in 1922, at just 19, to set up her own one-room studio in New Brunswick, New Jersey and advertise in the local business directory, “’Won’t you visit my studio, and let me perpetuate your personality.”

In July 1925, Louise left New Brunswick for Hollywood and opened a tiny studio on Vine Street and Hollywood Boulevard, close to the Famous Players-Lasky studio. Her first clients ranged from shooting aspiring actors’ publicity shots, to the producer, Samuel Goldwyn, who hired Louise to photograph his latest discovery, Vilma Bánky. Within weeks of arriving in Los Angeles, Louise had been introduced to Louis B Mayer, the head of MGM. Her youth, good looks and self-possession, as well as her work, impressed Mayer, who hired her on the spot and gave her her own studio. Louise shrewdly negotiated final approval of her photographs, full credit for all her work and the opportunity to photograph people outside the studio – terms that were not given to other studio photographers. Louise’s work was critical to MGM, helping to generate publicity and sell tickets for the studio’s most important films. Her photographs of Ramon Novarro, MGM’s answer to Rudolph Valentino, was vital in drumming up publicity for Ben-Hur, which desperately needed to recoup its spiraling budget of $3.9 million (making it the most expensive silent film ever made).

In September 1925, two months after she joined MGM, Louise photographed the new Swedish sensation, Greta Garbo. She immediately established a strong rapport with Garbo, and her images helped to shape the young star’s image into the ice-cool femme fatale she became and which Clarence Bull subsequently refined. The same year Louise started working with Garbo, she met Marion Davies, the mistress of the publisher William Randolph Hearst, and they became friends. She spent days with Davies at the star’s Santa Monica beach house and took informal shots of her diving into her magnificent pool, playing tennis or welcoming guests such as Charlie Chaplin and Gloria Swanson. In 1927 Louise married the writer and director Leigh Jason, with the director William Wyler as their best man. Her status was reinforced in 1928 when she was invited to photograph Herbert Hoover, the president elect, in Palo Alto, California. She made more Hollywood history in 1929 by shooting Nina Mae McKinney, dubbed the Black Garbo, for the first all-African-American film by a major studio.

But in September of that year Louise’s world collapsed. Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford’s famous rival, had decided she preferred the sexier glamour shots of George Hurrell to the cool elegance of Louise’s images. As mentioned above, Hurrell transformed Shearer into a slinky seductress with languorous poses, using heavy retouching and extreme close-ups that were a far cry from Louise’s more natural style. Her contract was not renewed. Louise left the studio in December 1929. Once the ‘talkies’ took hold, and the Great Depression hit, Hollywood became even more macho, reflecting the hard-boiled new male stars like Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney. Louise, with her unique talent, connections and easy bonhomie with her subjects, had acquired a special place in studio history, but would never again find the opportunities of her early career. During the 1930s she worked intermittently as a freelancer but her priority became her family.

In 1940 Louise became pregnant but there were complications with the premature birth and Louise and her son died. Had it not been for the sheer body of her work (over 100,000 images), and the iconic stars she photographed, Louise might have been completely forgotten.

Milton H. Greene (1922-1985)

Milton Greene became interested in photography as a teenager and began taking photos at the age of 14. Greene was awarded a scholarship to the Pratt Institute, but decided to pursue a career in photography instead. He apprenticed with photojournalist Elliot Elisofen and later worked as an assistant to Louise Dahl-Wolfe. Greene eventually began his own career and, at the age of twenty-three, became known as the “Color Photography’s Wonder Boy”.

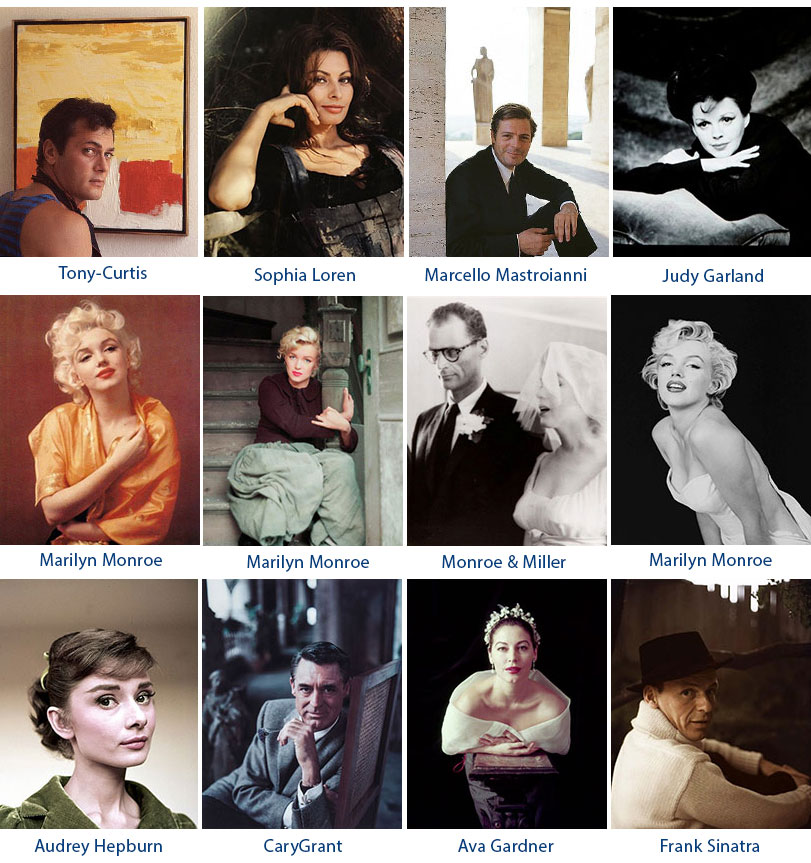

Greene initially established himself in high fashion photography in the 1940s and 1950s. His fashion shots appeared in Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue. Greene then turned to portraits of celebrities. He photographed many high-profile personalities in the 1950s and 1960s, including Elizabeth Taylor, Frank Sinatra, Audrey Hepburn, Grace Kelly, Ava Gardner, Sammy Davis, Jr., Catherine Deneuve, Marlene Dietrich, and Judy Garland. Greene’s work with Marilyn Monroe (whom he first shot for a layout for Look in 1953) changed the course of his career.

The two struck up a friendship and, when Monroe left Los Angeles to study acting with Lee Strasberg in New York City, she stayed with Greene, his wife Amy and young son Joshua in Connecticut. Together with Greene, Monroe formed Marilyn Monroe Productions, a production company in an effort to gain control of her career (from Hollywood powerhouses). Greene would go on to produce Bus Stop (1956) and The Prince and the Showgirl (1957). The two also collaborated on some 53 photo sessions, some of which became well known, including “The Black Sitting”. Greene’s photograph for one such sitting in 1954 featuring Monroe in a ballet tutu was chosen by Time Life as one of the three most popular images of the 20th century. Monroe and Greene’s friendship ended after the production of The Prince and the Showgirl in 1957 with Monroe firing Greene. Greene’s died in 1985.

Cecil Beaton (1904 –1980)

Beaton was one of the foremost photographers of the twentieth century, best known for his elegant and unusual shots of celebrities and royalty. His fascination with glamour and high society continued throughout his life and he was considered a style leader in his own right, known for his easy charm and wit as well as his flamboyance of dress and waspish comments on celebrity figures, a trait that prompted the writer Jean Cocteau to dub him “Malice in Wonderland”. He was also a prominent innovator in the relatively new field of fashion photography. In 1929, in his early twenties, he was hired by Condé Nast and chronicled the golden age of fashion with his 8×10 inch camera for the glossy pages of Vogue and Vanity Fair, lensing 20th-century icons from Marlene Dietrich to Pablo Picasso, Coco Chanel, Sergei Diaghilev, Lucian Freud, Albert Camus, Marilyn Monroe, and Grace Kelly, among endless others.

Working away from his familiar studio and its resources, and with sitters who habitually faced the lens, Beaton adopted new settings and props, and experimented with new formats. His portraits from this period, and through the 1930s, reveal an increasing reliance on close-ups of the face, often strongly modelled by contrasting light and shade, and also the increasing incorporation of floral motifs. These tropes give the images immediacy and freshness, and may even express the photographer’s attempts to respond more directly to the people in front of him. Yet, on closer inspection, they do not quite retain the natural quality that they first suggest. Beaton’s aesthetic remained highly artful if not so brazenly artificial, and made frequent nods towards Surrealism. The success Beaton achieved in the 1930s reached its height when he was summoned to Buckingham Palace in July 1939 to photograph Queen Elizabeth.

Working away from his familiar studio and its resources, and with sitters who habitually faced the lens, Beaton adopted new settings and props, and experimented with new formats. His portraits from this period, and through the 1930s, reveal an increasing reliance on close-ups of the face, often strongly modelled by contrasting light and shade, and also the increasing incorporation of floral motifs. These tropes give the images immediacy and freshness, and may even express the photographer’s attempts to respond more directly to the people in front of him. Yet, on closer inspection, they do not quite retain the natural quality that they first suggest. Beaton’s aesthetic remained highly artful if not so brazenly artificial, and made frequent nods towards Surrealism. The success Beaton achieved in the 1930s reached its height when he was summoned to Buckingham Palace in July 1939 to photograph Queen Elizabeth.

Throughout World War II, Beaton remained highly industrious, photographing for Vogueas well as Britain’s Ministry of Information, and designing for both stage and screen. His gradual development as a designer for stage and screen took off in a big way at the end of the war on both sides of the Atlantic. His contributions to the film versions of the musicals, Gigi (1958) and My Fair Lady (1964), by Lerner and Loewe, gained him Oscars and made him a household name. The films also gave him new muses in the shape of Leslie Caron and Audrey Hepburn. Beaton continued to work for Vogue throughout the fifties and the sixties, working on his last sitting for British Vogue in 1973. Cecil Beaton died at Reddish House, Broad Chalk, Wiltshire, on January 18, 1980.

Photographs Available At WalterFilm.com

(click to view image and description)

Content Resources

Albert Walter Witzel

Albert Witzel, Early Glamour Photography Pioneer

Witzel Studios, National Portrait Gallery

George Edward Hurrell

George Hurrell – The Master of Hollywood Glamour Photography

Clarence Sinclair Bull

Ruth Harriet Louise

Ruth Harriet Louise – Wikipedia

Star maker: the photographer Ruth Harriet Louise – Telegraph

Milton H. Greene

Cecil Beaton

- African American Movie Memorabilia

- African Americana

- Black History

- Celebrating Women’s HistoryI Film

- Celebrity Photographs

- Current Exhibit

- Famous Female Vocalists

- Famous Hollywood Portrait Photographers

- Featured

- Film & Movie Star Photographs

- Film Noir

- Film Scripts

- Hollywood History

- Jazz Singers & Musicians

- LGBTQ Cultural History

- LGBTQ Theater History

- Lobby Cards

- Movie Memorabilia

- Movie Posters

- New York Book Fair

- Pressbooks

- Scene Stills

- Star Power

- Vintage Original Horror Film Photographs

- Vintage Original Movie Scripts & Books

- Vintage Original Publicity Photographs

- Vintage Original Studio Photographs

- WalterFilm