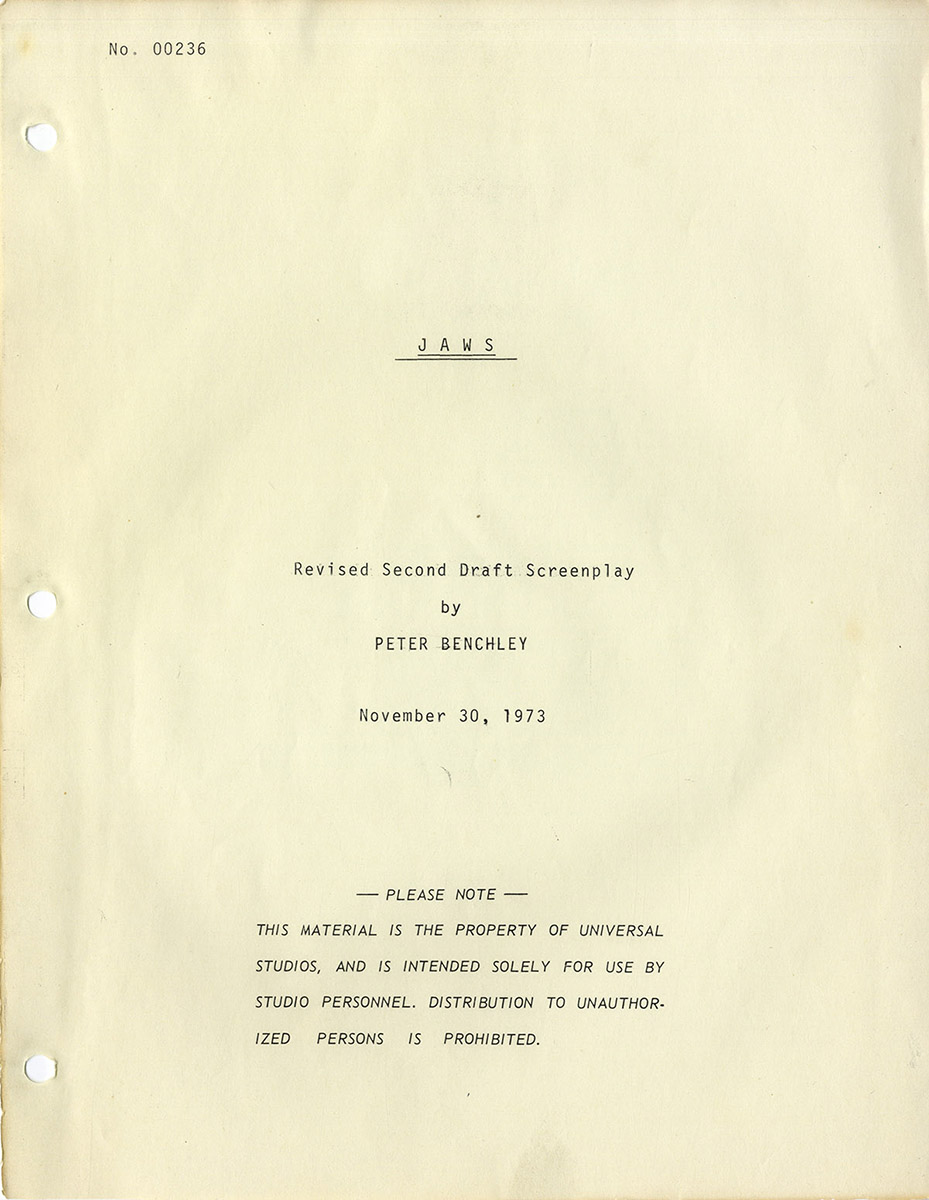

JAWS (Nov 30, 1973) Revised Second Draft screenplay by Peter Benchley

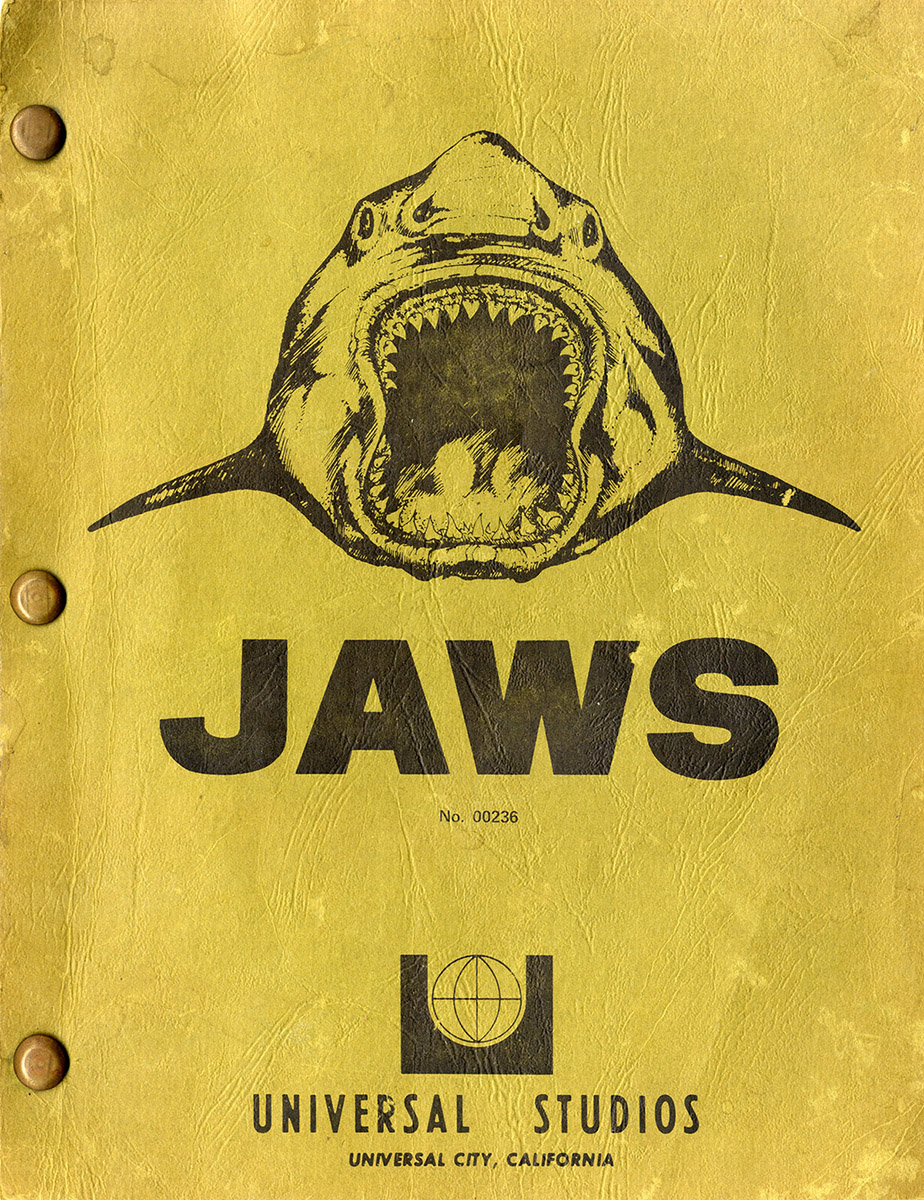

Peter Benchley (source) JAWS (Nov 30, 1973) Revised Second Draft Screenplay by Peter Banchley Universal City, CA: Universal Studios, 1973. Vintage original film script, , 11 x 8 ½” (28 x 21 cm.), pictorial wrappers, brad bound, mimeograph, [1], 121 pp., minor creasing and slight stains to wrappers, near fine in very good+ wrappers.

A very early draft of the script for JAWS, two years prior to its release in 1975, with an unusual artwork design on the front cover which was not present on subsequent scripts for this classic film.

JAWS was the second feature film directed by the 27-year-old Stephen Spielberg and became one of the highest grossing movies ever made, the prototype of the summer blockbuster, outgrossing even THE GODFATHER.

The movie went through a complicated pre-production process involving several directors prior to Spielberg, and numerous screenwriters, most of whom were uncredited. This is the Second Draft screenplay by Peter Benchley based on his novel, an eventual bestseller, which producers Zanuck and Brown had purchased the rights to some months prior to its publication. The film’s screenplay was ultimately co-credited to Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb, a comedy specialist best known for screenplays like Steve Martin’s THE JERK.

Although it was substantially revised before reaching the screen, Benchley’s Second Draft screenplay has the same fundamental structure as the completed film, most of the same incidents, and the same principal characters.

The screenplay and film are divided into two basic parts — Part 1: The Shark vs. the Community (the community’s growing awareness of the danger it faces), and Part 2: The Shark vs. Three Men on a Boat (the shark hunt). Part 1 is essentially a horror film (the scary shark attacks). Part 2 is essentially an action movie. Interestingly, some of the characters who are extremely important in Part 1 of the film — i.e., the Mayor of the town, and Sheriff Brody’s wife and his two sons — are completely absent from Part 2.

The character who was most altered between the Second Draft screenplay and Spielberg’s completed film was Hooper, the young shark expert. In Benchley’s screenplay, he is described as “handsome but disheveled,” a Jan-Michael Vincent type. In fact, Jan-Michael Vincent was the studio’s first choice for the part. Whereas the Hooper in Benchley’s screenplay was a daredevil type, someone who climbed mountains and chased lions before he became interested in sharks, the Hooper in Spielberg’s movie, as played by Richard Dreyfuss, is more of a science nerd, an ichthyologist fascinated by fish. Where the Hooper in Benchley’s screenplay is killed before the end of the story, the Hooper in Spielberg’s movie makes it out alive.

Quint, the macho sea captain who leads the shark hunt — played in the movie by Robert Shaw — was also somewhat altered. In the Second Draft screenplay, he is even more repellent than he is in the film. In the screenplay, he has a baby porpoise, caught illegally, which he plans to use for shark bait. One scene has him eating a raw fish, sucking out its eyeballs. In the movie, he is given a motivation for his shark hatred, a memorable monologue written largely by John Milius (uncredited) in which Quint describes being aboard the U.S.S. Indianapolis when it was sunk in 1945, and he had to float in the water for days, waiting to be rescued, while he watched the majority of his fellow crew members being eaten by sharks.

The movie’s everyman protagonist, Sheriff Brody — played in the film by Roy Scheider — was comparatively unchanged between this draft screenplay and the completed film. However, the scenes between Brody and his family were elaborated to give the character more warmth. The movie adds a scene, not in this draft, where one of Brody’s sons is menaced by the shark, making the danger more personal. Also, Spielberg had the idea of making Brody an aquaphobe, someone afraid of the water, making him even more human and identifiable.

Finally, where in both Benchley’s screenplay and the film, Brody is the one who ends up killing the shark, the way he kills it was changed. In the screenplay, Brody kills it with a harpoon through the creature’s eye; in the film, more ingeniously, he kills it by shooting and exploding a canister of compressed air lodged in the shark’s mouth.

Though Benchley’s screenplay has many of the same incidents that appear in the film, almost all of them were somewhat revised.

For example, both the screenplay and the film begin with a young woman, Christine, being killed by the shark while swimming naked in the ocean. However, the only characters in the screenplay’s version of this scene are Christine and her boyfriend who chases her into the water. The film begins with a nighttime beach party, during which Christine flirts with a young man she has never seen before who leaves the other partygoers to follow her drunkenly to the shore.

Also, in the film, Christine’s death scene is preceded by shots of the camera moving underwater — meant to represent the unseen shark’s point of view (this is, in fact, the film’s credit sequence) — while on the soundtrack we hear composer John Williams’ throbbing string motif which the audience comes to identify with the presence of the shark.

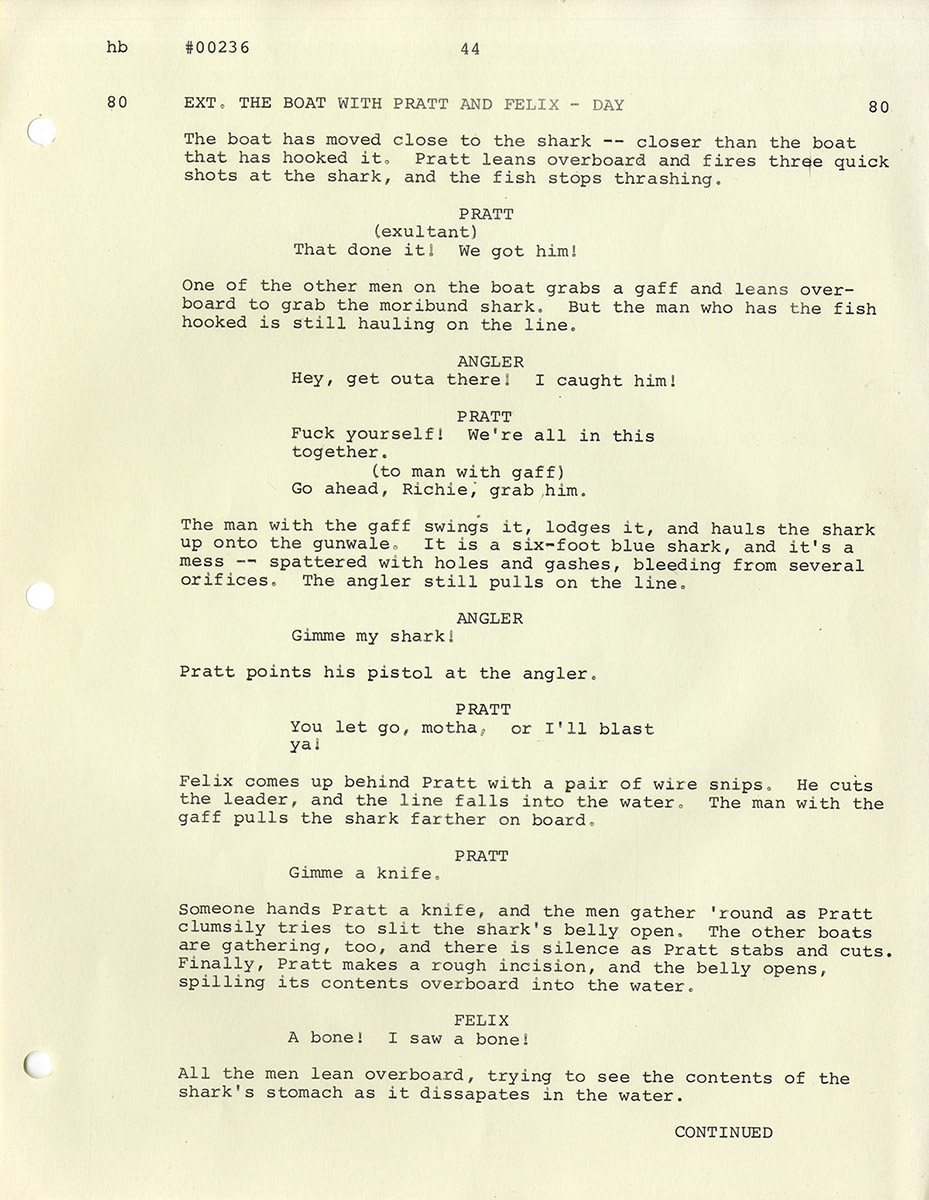

The film notably omits a lengthy sequence in Benchley’s screenplay in which a flotilla of boats manned by local citizens leave the town to hunt for the shark, and only succeed in getting in each others’ way.

Though the film was initially regarded as a pure thrill machine, it does have several interesting subtexts which are implicit in Benchley’s Second Draft screenplay.

The subtext of Part 1 — The Shark vs. the Community — is a critique of Capitalism as embodied in the town’s Mayor who wants to hush up and deny the presence of the shark in order not to disrupt the town’s tourist trade.

The subtext of Part 2 — The Shark vs. Three Men on a Boat — is the Generation Gap, pitting the old school toxic masculinity of Shaw’s Quint against the youthful proto-hippie persona of Dreyfuss’s Hooper. The movie elaborates on Benchley’s screenplay by adding scenes of male bonding — the three men drinking together, singing songs, comparing scars. At one point in the film, Shaw’s Quint crushes a beer can with his fist, while Dreyfuss’ Hooper responds by crushing a Styrofoam cup.

Like Nichols’ THE GRADUATE, Spielberg’s JAWS uses the Generation Gap to flatter its youthful audience — Quint is killed, devoured by the shark, while Hooper survives — and the audience responded by attending in droves, making JAWS one of the most popular movies of all time.

Out of stock

Related products

-

Brian De Palma (director, screenwriter) SISTERS (1970) Film script

$1,750.00 Add to cart -

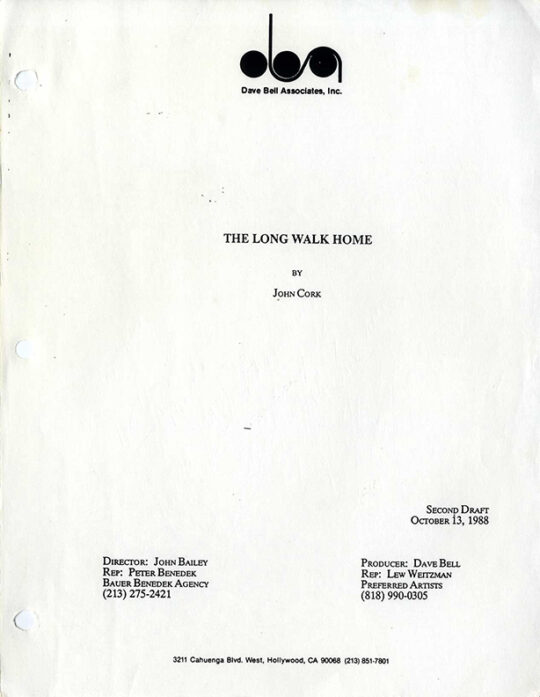

LONG WALK HOME, THE (Oct 13, 1988) Second draft film script by John Cork

$375.00 Add to cart -

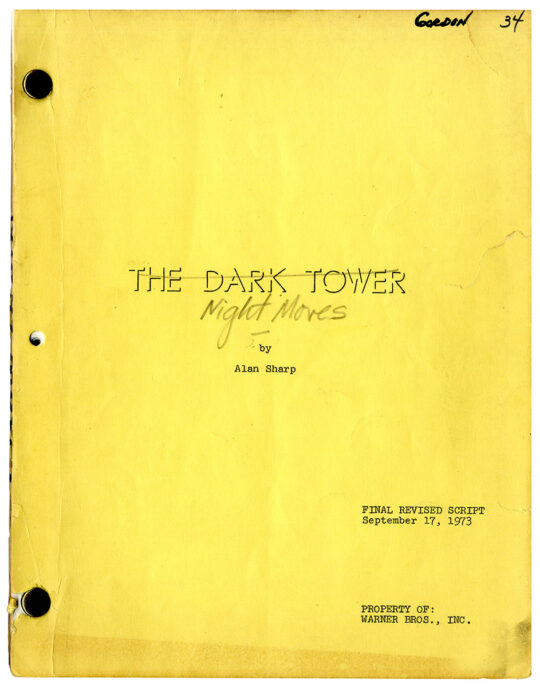

Arthur Penn (director) NIGHT MOVES [working title: THE DARK TOWER] (Sep 17, 1973) Final revised film script

$2,000.00 Add to cart -

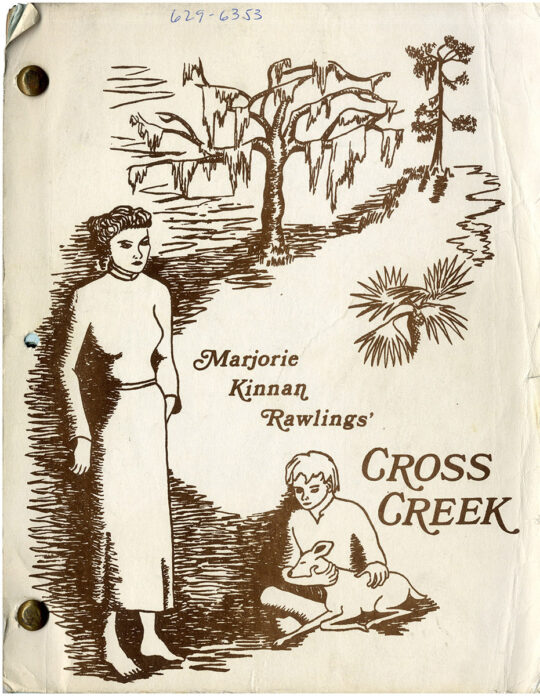

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart