IT’S ALIVE III: ISLAND OF THE ALIVE (1986) Larry Cohen-signed archive

Larry Cohen (screenwriter, director)

Consisting of:

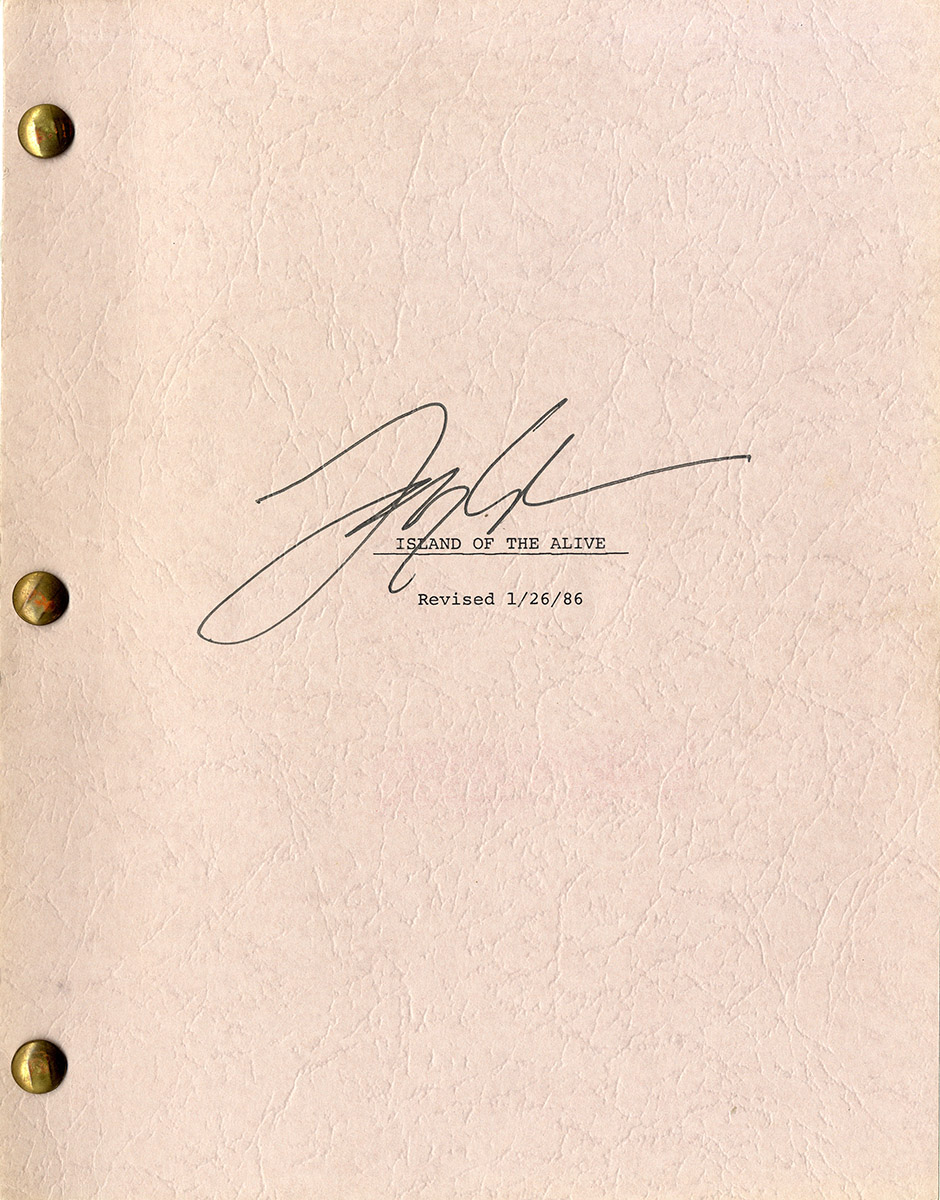

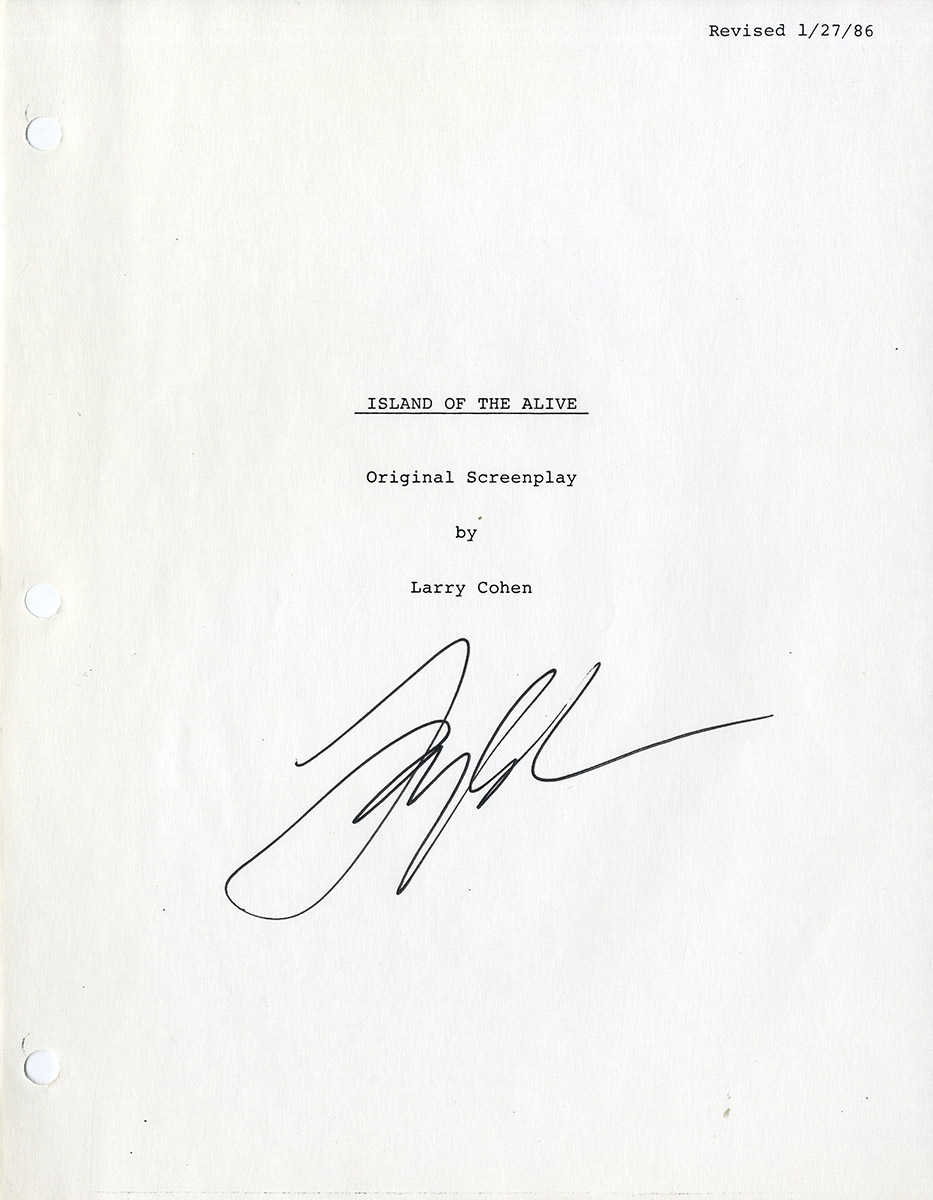

- Vintage original film script. Revised 1/26/86 Printed wrappers, 11 x 8.5″ (28 x 22 cm.), brad-bound, mimeograph, 117 pp. (with many pages of undated revisions on blue paper). Boldly signed by Larry Cohen on front wrapper. Just about fine.

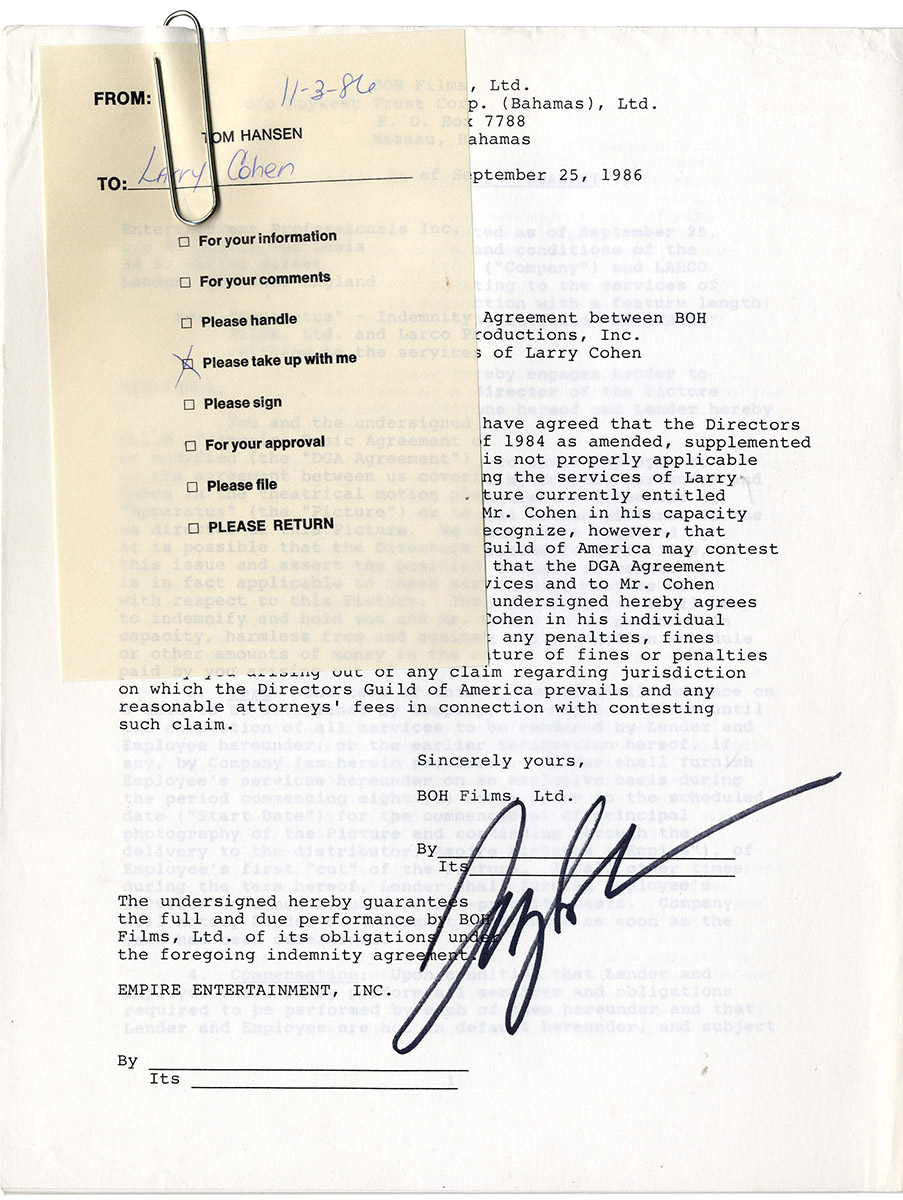

- Approximately 50 pp. of letters sent to Cohen about the production of the film and its subsequent marketing, and 2 letters sent by Cohen, one of them with a proposed cast list, several boldly later signed by Cohen.

- A reprint of Tony Williams’ interview, “Cohen on Cohen”, autographed by Cohen.

The original IT’S ALIVE (1974) was the biggest box-office success of writer/director Larry Cohen’s career, one of the highest grossing films Warner Brothers distributed during the 1970s. Inevitably there were sequels, both of them written and directed by Cohen, IT LIVES AGAIN (aka IT’S ALIVE II) released in 1978, and IT’S ALIVE III: ISLAND OF THE ALIVE, released in 1987.

The fascination of the mutant babies in IT’S ALIVE (“There’s only one thing wrong with the Davis baby … It’s alive“) and its sequels lie in the filmmaker’s ambivalent attitude toward them. On the one hand, they are super-strong “monsters”, grotesquely fearsome-looking, and homicidal when they feel threatened. On the other hand, they might represent the next necessary step in human evolution, genetically equipped to survive the increasingly polluted world that gave birth to them. The story arc of both IT’S ALIVE and IT LIVES AGAIN is that of initially repelled parents who eventually learn to accept and love their children, even though they are “different.” (And that “difference” could be a metaphor for any way in which a child is different from his or her parents, be it skin color, body type, sexual orientation, or religious or political beliefs.)

In the first film, there was one mutant baby who was killed at the end. In the second film, there were two mutant babies born to two other sets of parents. As for the third film:

“I thought if I was going to make a third movie, I had to follow this story through to some kind of new and satisfying resolution. So, I asked myself some questions: what are these babies like as adults? What is the monster going to look like when it physically develops and ages? I thought those were important questions to answer and deal with. Otherwise, there was no point in making the movie if I was just going to have a load of monster babies running around again, killing people. The second film was, to a degree, different from the first because the protagonists were trying to save the monsters. In the third film, we got all of the monster birth stuff out of the way in the prologue and gave the audience their horror. The rest of the movie was more of an exploration of Jarvis’ character and the progress of the monster children. I thought that differentiation from the events of the previous pictures made Island of the Alive a worthwhile project.” (Larry Cohen interviewed by Michael Doyle in his book, Larry Cohen: The Stuff of Gods and Monsters. BearManor Media, 2015.)

Cohen’s ISLAND OF THE ALIVE screenplay begins with one of the most conceptually brilliant set pieces to be found in any of Cohen’s movies, a courtroom scene whose resolution will affect the fates of all of the mutant babies, born and yet-to-be-born. On one side, we have the Special Prosecutor Ralston (Gerritt Graham) arguing for the State’s right to execute the dangerous mutant children — as it has been doing — on sight.

RALSTON

Your honor, let’s not let this be degraded into a maudlin display of sympathy by depicting these creatures as “infants”. I can’t account for them. Science can’t account for them. But let us never mistake them for human beings.

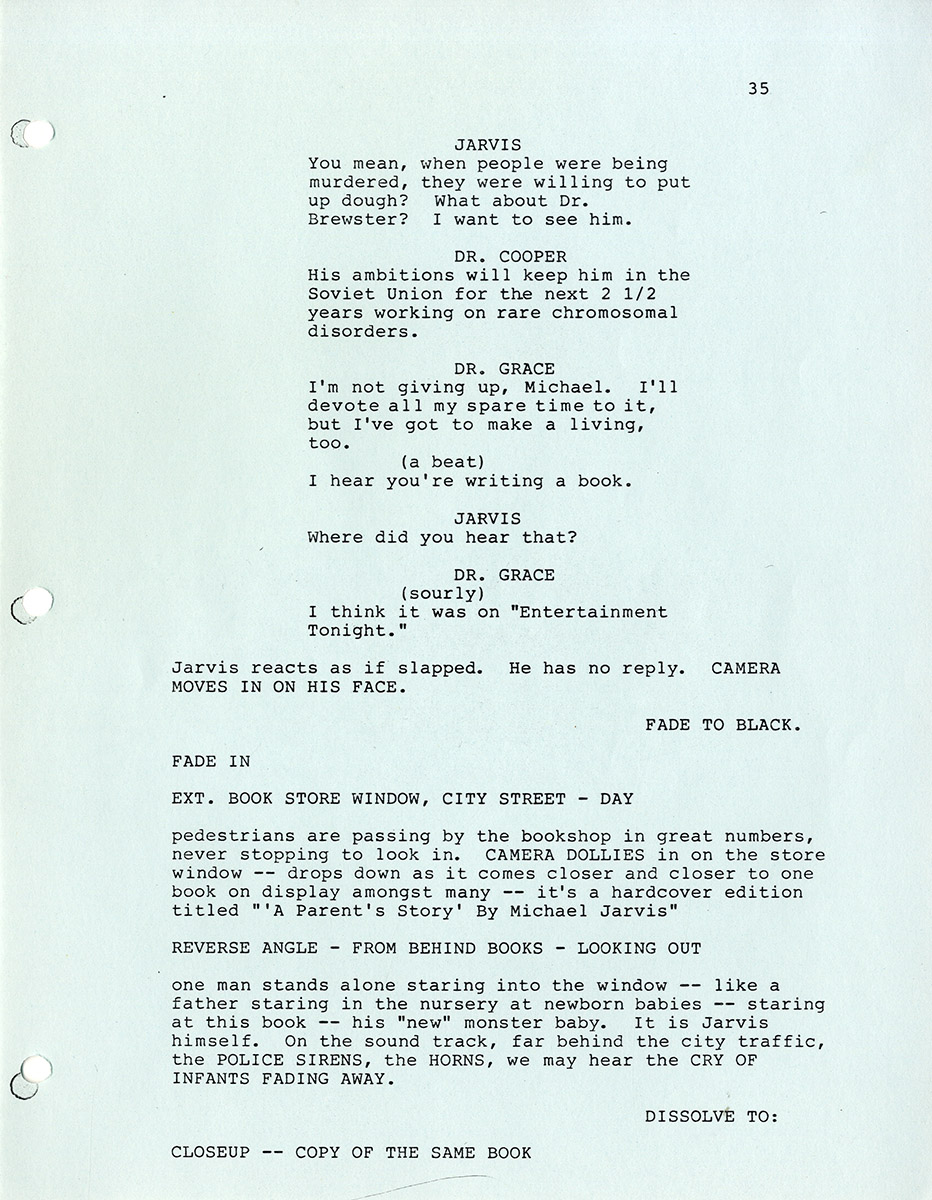

On the other side, we have the plaintiff’s attorney, Robbins (a male in the screenplay, but played by a woman in the film), and her client, the story’s protagonist, Jarvis, played by Cohen’s favorite leading actor, Michael Moriarty, who argue for the mutant babies’ right to survive — in particular, his mutant baby. The scene intensifies when Jarvis’s baby is unexpectedly brought into the courtroom, caged, angry, and enchained, with a metal collar around his neck. Jarvis’s attorney tells him that if the prosecutor can show the elderly judge (Macdonald Carey) that Jarvis is afraid of his own child, then he’s won. Jarvis confides to his attorney:

JARVIS

I don’t want him to die, but I’m scared shitless of him.

Jarvis is asked to approach the cage, and identify the creature. He does so, with great trepidation, and goes even further than asked, placing his hand inside the cage to caress the infant. However, when a security guard reaches for his gun, the frightened creature breaks out of its cage and leaps onto the judge’s bench. Jarvis intervenes, calming the “monster child” who begins to cry (!) as Jarvis takes it into his arms. The judge, concluding that the baby is human after all, orders that the executions shall cease, but that the five surviving mutant children shall be quarantined to a remote tropical island, away from all human contact, setting up the story’s basic premise.

Cohen addresses some very hot button issues in this sequence, notably the “right to life.” One major difference between this screenplay and the completed movie is that the movie adds a horrific prologue in which a woman gives birth to one of the mutant babies inside a New York cab, and a cop fires four bullets into the child who murders him in return. Investigators later discover the body of the baby in a church where the wounded infant has crawled to baptize itself before dying — adding a surprisingly Roman Catholic twist to a film directed by a Jewish-American auteur. Another major difference between the screenplay and the film is the degree to which Cohen and his leading actor Moriarty improvised lines and business on the set, for example, Jarvis telling his frightened child in court not to “let the assholes win.”

The screenplay then introduces us to Jarvis’s estranged wife, the child’s mother (Karen Black), who is working under another name in a Florida bar. Failing to reconnect with her, Jarvis is picked up by a prostitute in an amusement park arcade who becomes horrified after sleeping with him and realizing that he is the notorious “father of the monster.” In an audio commentary, Cohen recalled critics who interpreted this scene as a comment on the ’80s AIDS crisis (the fear of being in contact with someone who had the disease), and Cohen stated that this was, in fact, his intention.

There are two expeditions to the island where the babies are quarantined. The first is sponsored by a pharmaceutical manufacturer who wants to prove its product is not responsible for the mutations. All of the members of that expedition are slaughtered. The screenplay has two additional island-related scenes not included in the completed movie. In the first, we see a board meeting of the pharmaceutical executives planning the expedition and its objective — to murder the infants. In the second unfilmed sequence, a French photographer and his crew of beautiful bikini models land on the island, with predictably disastrous results.

Five years pass, and there is another expedition, scientific in purpose, bringing along Jarvis in the hope that he can act as intermediary between the scientists and the children. Most of that expedition, to the extent they are perceived as threats, are also slaughtered by the children — who are now full-grown, telepathic, and capable of reproduction — and the screenplay’s final act sees the mutants and Jarvis sailing the expedition’s boat to Florida to find the Jarvis child’s mother.

In his audio commentary, Cohen said the principal difference between ISLAND OF THE ALIVE and the earlier IT’S ALIVE films is the amount of manic humor in the screenplay, an element that became more and more pronounced in his movies after he began working with Michael Moriarty in Q: THE WINGED SERPENT (1982). ISLAND OF THE ALIVE mixes drama, outrageous humor, wild imagination, and social commentary in a manner unique to Larry Cohen.

In stock

Related products

-

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart -

LOOT (ca. Sep 1969) Final Draft screenplay

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

SAND PEBBLES, THE (Nov 1, 1965) Shooting script by Robert Anderson

$1,150.00 Add to cart -

ALL THE YOUNG MEN (Sep 15, 1959) Revised Final Draft script by Hall Bartlett

$450.00 Add to cart