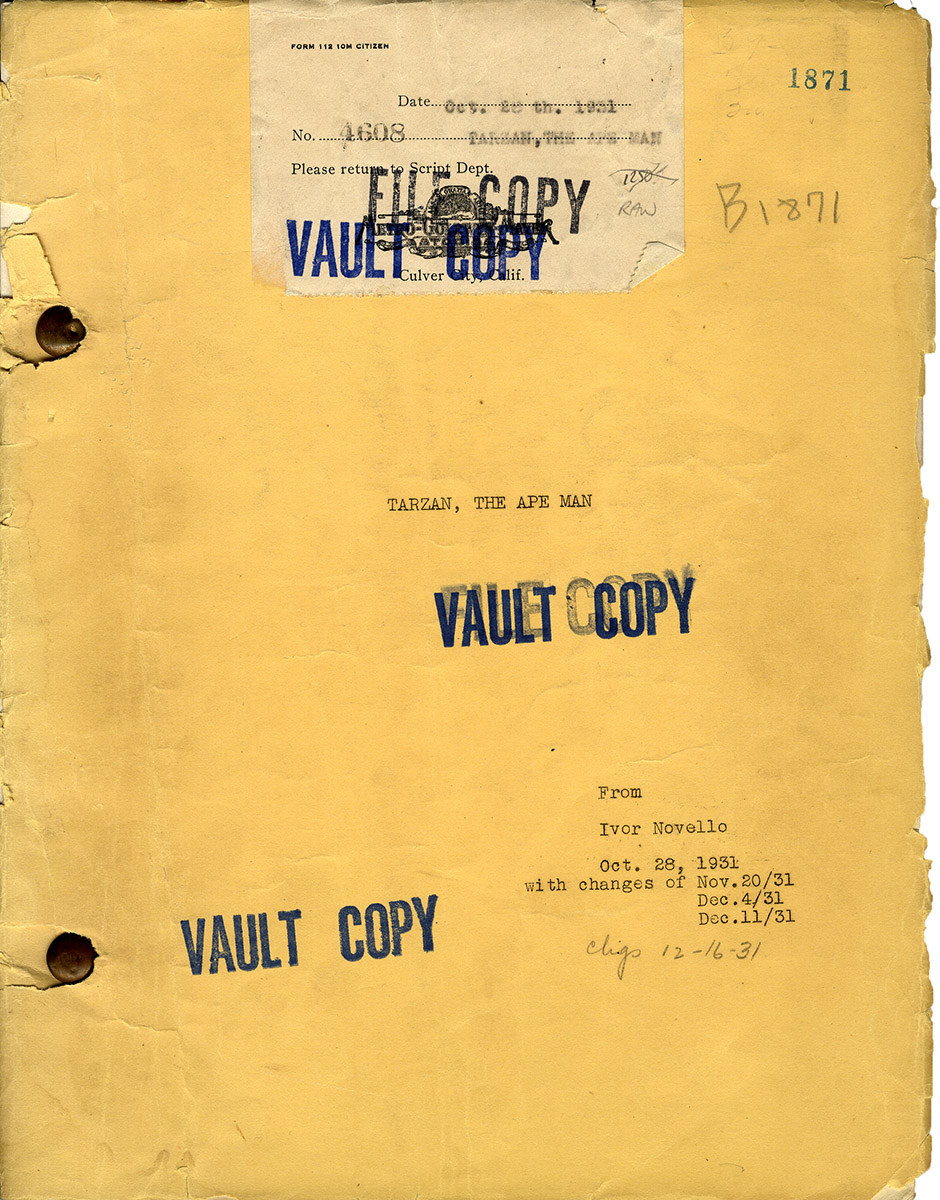

TARZAN THE APE MAN (1931) Film script by Cyril Hume, Ivor Novello

Based on the characters created by Edgar Rice Burroughs. [Hollywood: MGM, 1931]. Vintage original film script, quarto, printed wrappers, brad bound, mimeograph, 116 pp., with white revision pages throughout dated between 11-20-31 and 12-16-31. Front wrapper detached (but present), overall near fine in very good wrappers. With two vintage original photos laid in, both fine.

The screen credits of TARZAN THE APE MAN (1932) read “Adaptation by Cyril Hume; Dialogue by Ivor Novello”. In other words, Hume was chiefly responsible for the film’s story construction and what happens in each scene, while Novello wrote what the actors say. Both men were significant figures in twentieth century culture.

TARZAN’s adapter, Cyril Hume (1900-1966), a descendent of the Scottish philosopher David Hume, was the screenwriter of more than two dozen film projects, dating back to the early 1930s, before he co-authored the screenplay of Nicholas Ray’s 1956 masterpiece, BIGGER THAN LIFE. His other most notable film, Fred McLeod Wilcox’s FORBIDDEN PLANET, was released the same year as BIGGER THAN LIFE and can be seen as BIGGER THAN LIFE’s science-fictional twin. Both films are fables of megalomania and addiction — James Mason’s character in BIGGER THAN LIFE is addicted to cortisone, while Walter Pidgeon’s Dr. Morbius in FORBIDDEN PLANET is addicted to the mind-expanding qualities of an alien “plastic educator”. If any one person could be said to be the auteur of that sci-fi landmark, it was Hume, and the same could be said of this classic TARZAN film.

Ivor Novello (1893-1951) was a major celebrity of his era, particularly in his native Great Britain. A strikingly good-looking actor, known for his work on stage and screen, he starred in Alfred Hitchcock’s THE LODGER (1924) and its 1932 sound remake. He was also a singer and popular songwriter whose first big hit, “Keep the Home Fires Burning”, was composed in 1914. Finally, he was a playwright and screenwriter, achieving his greatest success as the author and composer of a string of musical comedies. According to The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Novello was “until the advent of Andrew Lloyd Webber, the 20th century’s most consistently successful composer of British musicals.”

Hume’s adaptation of TARZAN is a fable of another sort, the story of a “natural” man who grew up among the animals of the African jungle, uncontaminated by human civilization, and about the adventurous English girl, Jane Parker, who meets and falls in love with him. Like KING KONG, released the following year, it is a variation on the archetypal theme of Beauty and the Beast.

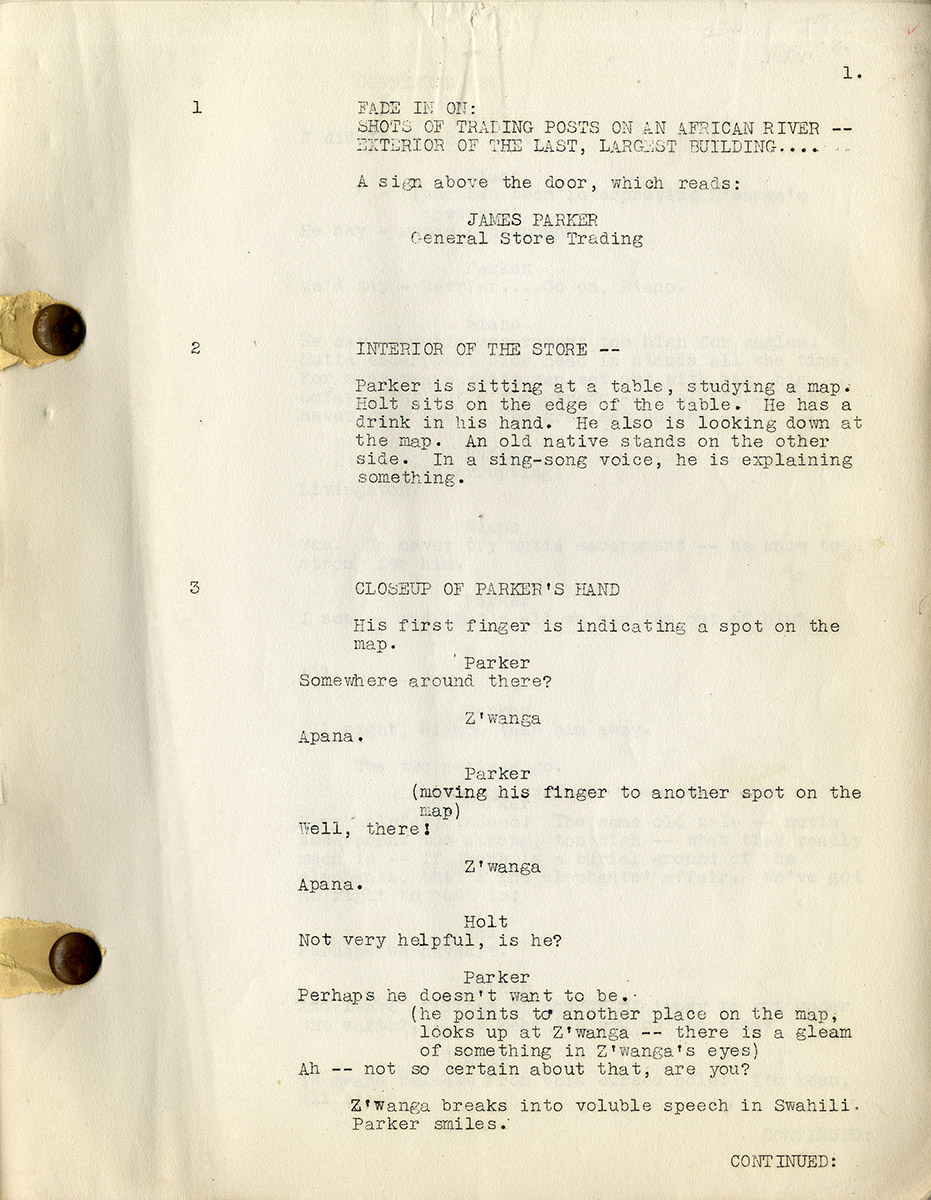

TARZAN, THE APE MAN is loosely based on Edgar Rice Burroughs’ 1912 serialized novel, Tarzan of the Apes, a story that had already spawned several adaptations and sequels during the silent era. The 1932 sound TARZAN, THE APE MAN is not particularly faithful to Burroughs’ original. In the novel, Tarzan is the baby son of an English Lord and his wife marooned on the African coast. When his parents die, the baby is adopted and raised by a tribe of apes, learning their language and ways. Later, he teaches himself to read English using his parents’ books. In the 1932 film, Tarzan’s origin is a mystery, and he has no language. (No mention is made of the fact that by birth he is an English lord.) In the book, Jane’s last name is Porter, she is an American from Baltimore, Maryland, and she meets Tarzan when she and her father are marooned in his part of the jungle. In the 1932 film, Jane’s last name is Parker, she is English, and she meets Tarzan while on an expedition with her father, and his business partner, Holt, who are searching for ivory. The film’s basic plot, the Englishmen’s search for the elephants’ graveyard where ivory might be found, was invented by the screenwriter.

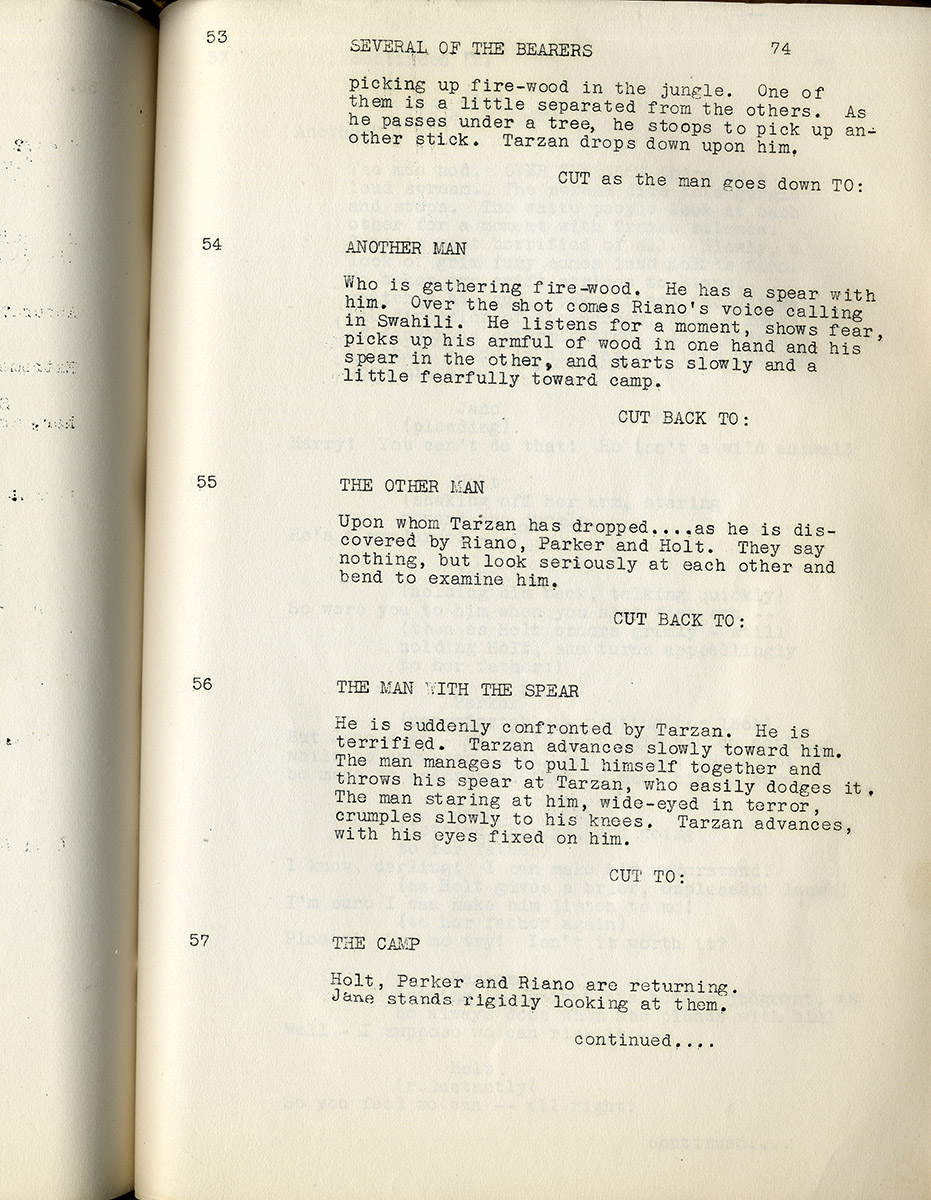

Much of the 1932 film’s lasting appeal, sufficient to engender five sequels, lies in the inspired iconographic casting of Olympic swimmer Johnny Weismuller as the inarticulate Tarzan, and vivacious Irish actress Maureen O’Sullivan as Jane. Director W.S. “Woody” Van Dyke (THE THIN MAN), known for his rapid shooting style, keeps things moving and was probably responsible for trimming the screenplay’s dialogue where possible. He is particularly adept in the scenes where Jane teaches Tarzan a few words of English (parodied as “Me, Tarzan. You, Jane”), and where the couple frolic erotically in a river. More distressing are the scenes involving black people, reflecting the casual racism of the era. The “good” black people who serve their white masters are treated as barely human, and the scenes involving “bad” black people — in particular a violent sequence involving dwarfs wearing blackface — are extremely difficult to watch. The imperialist assumptions that underlie the story are never questioned — unlike its immediate sequel, TARZAN AND HIS MATE (Cedric Gibbons, 1934), which subverts those assumptions and makes the white hunters who invade the jungle to steal ivory unambiguously the bad guys.

A note re: Tarzan’s ape and monkey friends — In the movie, the larger ape characters are played by actors in suits, while the smaller apes, like Cheetah, are played by actual chimpanzees. In the screenplay, there is also a little monkey who befriends Jane and acts as a go-between for Jane and Tarzan. Perhaps due to training difficulties, the little monkey character does not appear in the movie.

Film scholars looking for common themes in the movies authored by screenwriter Cyril Hume may note that in both TARZAN THE APE MAN and in FORBIDDEN PLANET, written 24 years later, there is a strong relationship between the father (played by C. Aubrey Smith in the 1932 film) and his daughter, and that in both films the father dies at the end, leaving the daughter free to start a new life with her boyfriend (i.e., in the 1932 film, leaving Jane free to stay in the jungle with Tarzan).

The screenplay and film end on a lyrical note: “JANE AND TARZAN — They stand. The sun is setting. It strikes their faces and heads and follows the lines of their bodies. Jane throws her head back and her arms as though she would leap into the air. Tarzan throws his head back and utters his cry, but this time there is nothing mournful in it. There is exultance and joy. FADE OUT”

Out of stock

Related products

-

![LES CREATURES [THE CREATURES] (1966) French film script](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/LesCreaturesSCR_a-540x689.jpg)

Agnès Varda (screenwriter, director) LES CRÉATURES (1966) Film script

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

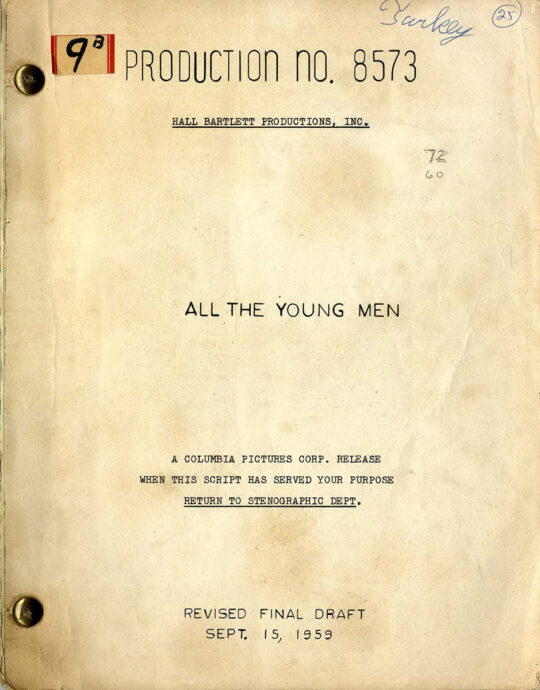

ALL THE YOUNG MEN (Sep 15, 1959) Revised Final Draft script by Hall Bartlett

$450.00 Add to cart -

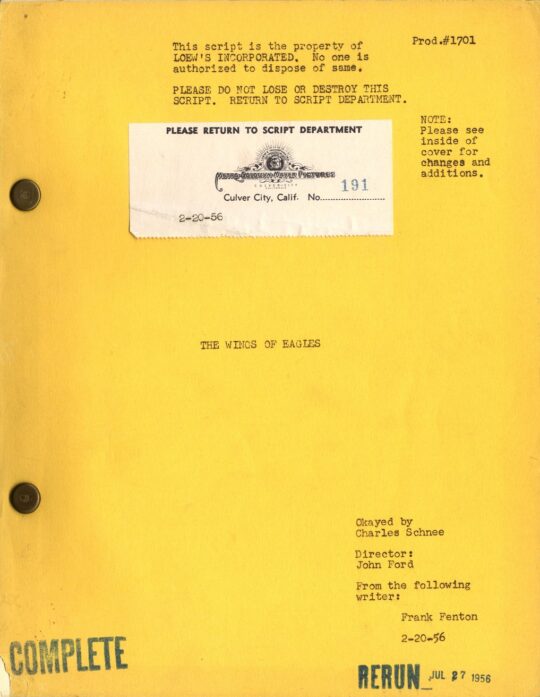

WINGS OF EAGLES, THE (1957) Two variant film scripts

$2,650.00 Add to cart -

![ESCAPADE [working title for: A WARM DECEMBER] (Jun 11, 1971) Revised First Draft screenplay](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/EscapadeSCR_a-540x695.jpg)

ESCAPADE [working title for: A WARM DECEMBER] (Jun 11, 1971) Revised First Draft screenplay

$500.00 Add to cart