FLY, THE (1986) Film script by David Cronenberg and Charles Edward Pogue dated Sep. 5, 1985

David Cronenberg (screenwriter, director) Vintage original film script by David Cronenberg and Charles Edward Pogue from the story by George Lanelaan, dated September 5, 1985.” Blue titled wrappers, dated September 5, 1985. Title page present, dated September 5, 1985, with credits for screenwriters Cronenberg and Pogue, and for writer Langelaan. 94 leaves, FINE in NEAR FINE printed wrappers, brad bound.

Following an arduous production process, “The Fly” was released in 1986 to favorable reviews. This remake of the 1958 science-fiction film outlines the horrific repercussions of an experiment gone awry. Eccentric inventor Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) begins to undergo an unexpected and horrific mutation when a common house fly slips into his newly invented teleportation device. Winner of Academy Award for Best Makeup and three Saturn Awards.

David Cronenberg’s THE FLY is one of those rare movie remakes that most viewers consider superior to the original. Indeed, the 1958 film version is not credited. Instead, this version’s screenplay credit reads simply, “From the Story by George Langelaan,” though it has significantly less to do with that story than the comparatively faithful 1958 version. Still, the basic concept of the story is shared by both films: Man + Fly + Teleportation Machine = Fly-Man. (What we don’t get in the ’86 version is the ’58 version’s brilliantly Kafkaesque closing image – the tiny fly with the man’s head caught in a spider’s web screaming, “Help meeee!”)

Surprisingly, this film was not a Cronenberg project to begin with. The project originated with Charles Edward Pogue, a screenwriter (PSYCHO III) and playwright with ties to Twentieth Century Fox, whose agent and manager suggested it would be a good idea for Pogue to write a treatment based on a property already owned by Fox (Langelaan’s short story seemed like the best candidate) in the hopes that someone at the studio might be interested in developing it further. Pogue’s most significant contribution was to scrap the story’s idea of the man and the fly switching heads, and instead write a screenplay in which the man and the fly’s genetic materials are intermingled by the teleportation machine, causing the man to become steadily more fly-like.

The studio agreed to distribute the film, but only if Pogue and Fox producer, Stuart Cornfeld, could find someone else to finance it. Cornfeld brought the project to Mel Brooks, with whom he had made THE ELEPHANT MAN, and Brooks agreed to finance it through his production company, Brooksfilm. After a false start with another director, they ultimately hired David Cronenberg to direct.

In fact, Cronenberg had been the production team’s original first choice, but, up to that point ,he had been busy writing and preparing to direct TOTAL RECALL, a huge project from which he was ultimately dismissed. When Cronenberg read Pogue’s screenplay, he was surprised at how close it was to his own style and concerns. Cronenberg says that he kept most of Pogue’s story structure, and that his main contribution to this script (credited to both writers) was dialogue and characterization.

THE FLY clearly aligns with the themes and motifs expressed in earlier Cronenberg movies like THEY CAME FROM WITHIN, RABID, THE BROOD, and SCANNERS, i.e., an ambivalent fascination/repulsion with respect to bodily transformation and sex – critics like to refer to this as “body horror” – and the interrelationship of man and machine. However, the term “body horror” does not do full justice to Cronenberg’s intentions, since in many ways he sees bodily transformation/mutation as a good thing, a step toward a better future. Hence, the rallying cry of Cronenberg’s 1983 film VIDEODROME – “Long Live the New Flesh!”

n addition to Cronenberg’s usual preoccupations, THE FLY has two significant subtexts, particular to the time when it was made. The first is drug use. The initial reaction of Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) to his transformation, which includes increased strength and sexual stamina, is exhilaration and megalomania, like a person addicted to methamphetamines or cocaine.

The second is AIDS. Released at the height of the AIDS crisis in 1986, THE FLY – arguably more than any other film released during this time period – metaphorically communicates the horror of AIDS, the terror of experiencing a deteriorating body in revolt against itself, or, from the point of view of a loved one (the character played by Geena Davis in the film), the pain and helplessness involved in watching a partner succumb to a gradually wasting disease.

Script to Screen

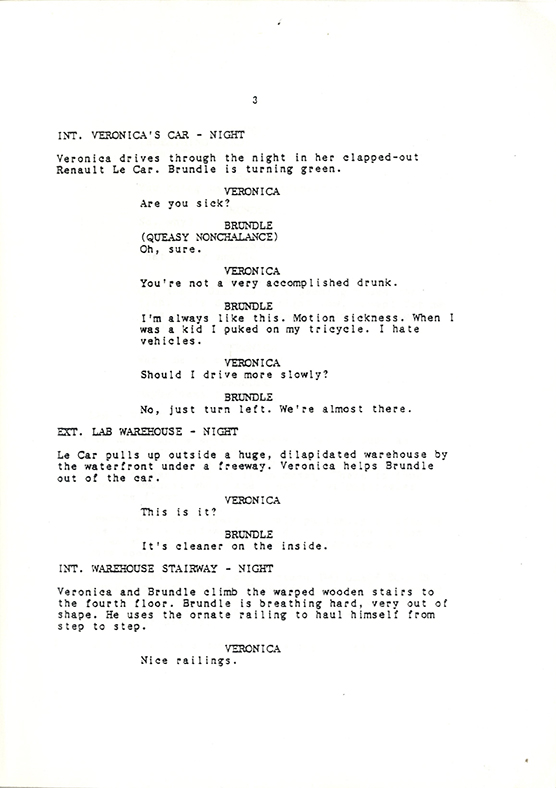

Most of the differences between this highly readable screenplay and the released film are the inevitable results of casting and the shooting/editing process. For example, in the first scene between the scientist played by Goldblum and the journalist played by Davis, taking place in the scientist’s laboratory/loft, Goldblum improvises on the piano as he talks to Davis. The piano is not in the screenplay, and its appearance in the film can be attributed to the fact that actor Goldblum was also a skilled piano player.

The love story is much stronger in the film than in the screenplay. This is not due to any significant changes in the dialogue, but to the extraordinary chemistry between actors Goldblum and Davis, who were partners in real life.

The film ends with Davis’s shooting (mercy-killing) of Goldblum’s fly-man character. The screenplay has two additional scenes, both dreams. In the first, Davis – who was impregnated by Goldblum’s character – gives birth to a horrible maggot-baby. In the second, she gives birth to a beautiful butterfly-child. In fact, both of these scenes were shot, along with a couple of other alternate endings. Everyone concerned concluded that the shooting of “Brundle-Fly” made the most dramatically effective ending. The maggot-baby dream was ultimately transposed to a spot earlier in the film. As for the butterfly-child dream, Cronenberg and his collaborators thought that the special effects didn’t do the concept justice. If the butterfly-child ending had been used, it would have more accurately reflected Cronenberg’s attitude toward transformation/mutation – that it is not necessarily a bad thing.

![[Doyle, Arthur Conan (source work)]: "SHERLOCK HOLMES FIGHTS BACK" [released as: SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SECRET WEAPON] 22 May - 17 June 1942](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/SherlockHolmesFightsBack-Script1-120x120.jpg)