AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON (1980) Script

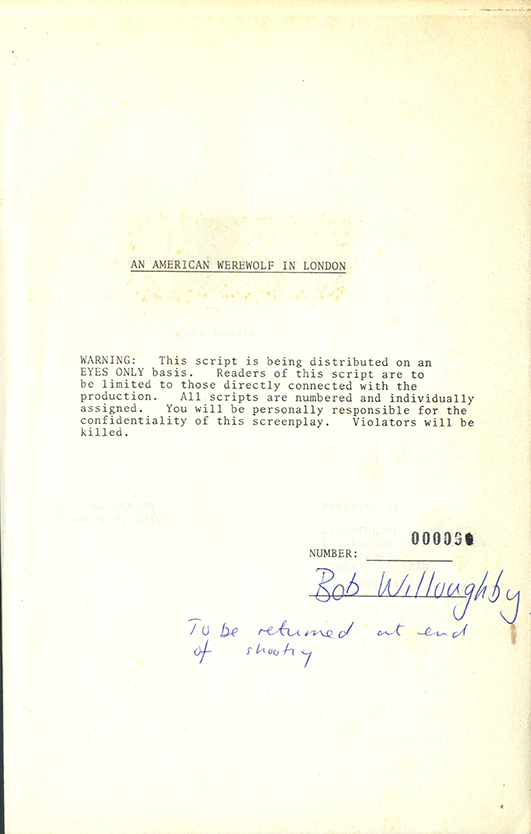

London: Lycanthrope Films Ltd., 1980. Shooting script for the 1981 film. From the collection of still photographer Bob Willoughby, with his ownership name in holograph blue ink on the distribution page.

Bob Willoughby (1927-2009) studied with Saul Bass at the Kann Institute of Art in Los Angeles, worked as a photographer for magazines such as “Life,” “Look,” and “Harper’s Bazaar,” and as a set photographer for every major studio, documenting some of most important films of the era and creating intimate portraits of some of Hollywood’s greatest celebrities.

Willoughby moved his family to County Cork, Ireland in 1972, working on only a handful of films through the late 1970s and early 1980s (this was one of his final films), though he would continue to photograph, exhibit, and publish books for the remainder of his life.

Landis was fresh off his previous year’s production, “The Blues Brothers,” when he directed this Academy Award-winning (Best Makeup) horror thriller, about two Americans, David and Jack (Naughton and Dunne) ,backpacking in England. One night they are attacked by a mysterious creature, a werewolf, leaving Jack dead and David wounded. Soon David’s nightmares depicting his dead friend warning that he’ll soon become a werewolf begin to get the better of him, and arouse suspicion amongst the locals. The film also contains one of cinema’s best man-to-monster transformations, similar in effect to Joe Dante’s “The Howling” (also 1981), and expands on a plot that began in 1941 with George Waggner’s “The Wolf Man.”

AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON may not have been director John Landis’s most financially successful film (the $62 million it earned at the box office is modest compared to the $141.6 million earned by Landis’s ANIMAL HOUSE (1978) or the $115.2 million earned by his THE BLUES BROTHERS (1980)), but it is probably his most technically accomplished and aesthetically satisfying achievement.

AMERICAN WEREWOLF was something of a dream project for Landis. The first draft was written in 1969 – eleven years before the movie was actually made – while Landis was working as a production assistant in Yugoslavia on the film KELLY’S HEROES. It was also a difficult screenplay for Landis to market. Because of the way it combines horror with comedy, some potential producers considered it too funny to be a horror film, while others considered it too scary to be a comedy.

The two most memorable aspects of the movie situate it firmly in the horror genre: (1) the incredibly realistic manner in which David (David Naughton) transforms from man into wolf, unlike anything seen in horror films of previous decades, and (2) the increasingly grisly appearances of David’s “undead” best friend, Jack (Griffin Dunne), who was killed by a werewolf. The Oscar-winning makeup and special effects were provided by Rick Baker, a technician and friend of Landis who has worked with him since his first feature, SCHLOCK (1973). The fact that AMERICAN WEREWOLF works so well for audiences as both a horror movie and a comedy is due in large part to Landis’s screenplay. The writer/director has a remarkable talent for knowing how what he writes on the page will play on the screen.

A Jewish Horror Film

AMERICAN WEREWOLF is not the first “Jewish” horror film. THE GOLEM (Paul Wegener, 1915) and THE DYBBUK (Michał Waszyński, 1937) were both inspired by Jewish legends. But AMERICAN WEREWOLF is genuinely innovative in the way it brings the Jewish-American sensibility of comic creators like Woody Allen into the realm of the horror movie.

The Jewishness of AMERICAN WEREWOLF’s male leads is immediately apparent from their names (David Kessler and Jack Goodman) and the names of the people they talk about (Debbie Klein). When David is hospitalized following the initial werewolf attack, one of his nurses comments, “I think he’s a Jew.” 2nd Nurse: “Why on earth do you say that?” 1st Nurse: “I looked.”

In the movie, Jack refers to David as a “putz” and a “schmuck.” (Both words added in the transition from script to film, possibly improvised.) However, the most remarkable manifestation of the film’s fundamentally Jewish sensibility is in one of its set-piece dream sequences – David’s parents and his little brother and sister are sitting in their suburban living room watching television. Four horrible “demon-beasts” wearing Nazi storm trooper uniforms burst into the room, attacking and murdering the family with machine guns and knives. Among the things they shoot up is a Menorah – an archetypally Jewish nightmare.

Script vs. Screen

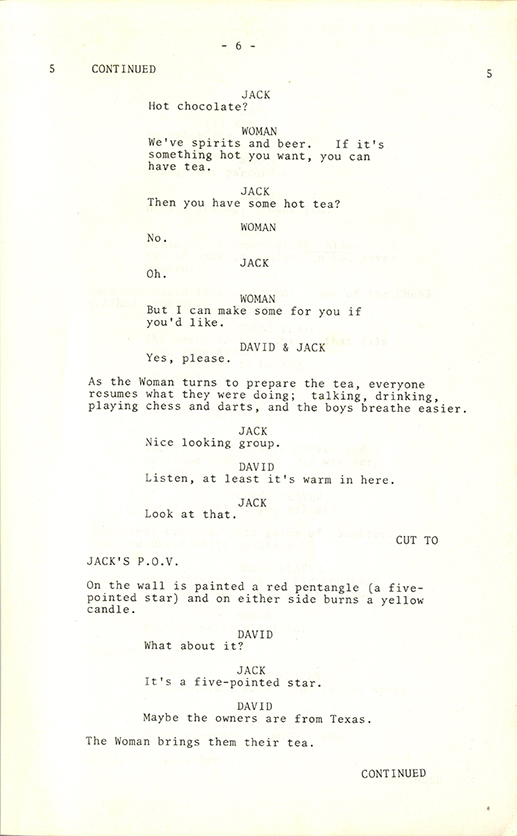

For the most part, director Landis was scrupulously faithful to writer Landis’s shooting script. Some dialogue is cut for streamlining purposes. Elsewhere in the film, scenes are supplemented with additional quips and bits of business. Example: In the opening scene, David and Jack have been hitching a ride in the back of an English sheepherder’s truck along with his sheep. When Jack hops off the truck, he says, “Bye girls!”

A more serious addition occurs in the scene where David telephones home to his parents for the last time. In the film, after he hangs up, he attempts to slit his wrist, but discovers his skin cannot be cut.

According to the script, Cat Stevens’ “Moon Shadow” was supposed to play over the opening title. However, Landis could not obtain the rights, so in the film “Blue Moon” is played instead.

There a few scenes in the shooting script that do not appear in the film. In one, a nurse tells hospitalized David about a film she is going to see with Nurse Alex (Jenny Agutter) who is David’s love interest. In another, the longest deleted scene, David flirts with Nurse Alex and wishes she could come to America with him. Most likely, these scenes were shot, but discarded during the editing process.

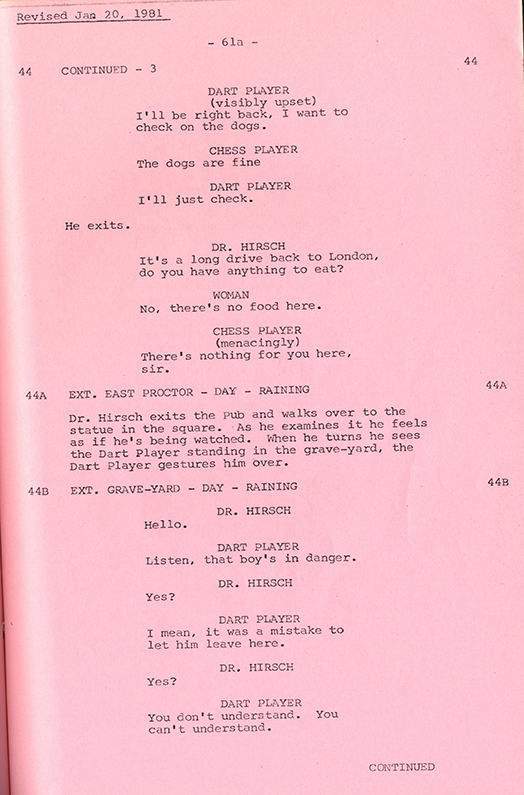

Dark green titled wrappers with a die-cut title window in the British style. Distribution page present, with Bob Willoughby’s signature in holograph blue ink. Title page present, dated December 9, 1980, noted as SHOOTING SCRIPT, with credits for screenwriter Landis. 103 leaves, mechanically reproduced, with pink revision pages, dated Jan. 20, 1981. Pages Near Fine, wrapper Very Good plus bound internally with two silver brads.

Collation: [distribution page, signature], [title], [1], 2-60, 61 (pink, Jan. 20, 1981), 61a (pink, Jan. 20, 1981), 61b (pink, Jan. 20, 1981), 62-99.

Out of stock