Paul Robeson – African American Superstar

Paul Robeson was a famous African-American athlete, singer, actor, and advocate for the civil rights of people around the world. During the first half of the 20th Century, he rose to international prominence in a time when segregation was legal in the United States, and Black people were being lynched by racist mobs, especially in the South.

Early Years

Born on April 9, 1898 in Princeton, New Jersey, Paul Robeson was the youngest of five children. His father was a runaway slave who went on to graduate from Lincoln University, and his mother came from an abolitionist Quaker family. Robeson’s family knew both hardship and the determination to rise above it. His own life was no less challenging.

Star Athlete and Academic

In 1915, Paul Robeson won a four-year academic scholarship to Rutgers. Despite violence and racism from teammates, he won 15 varsity letters in sports (baseball, basketball, track) and was twice named to the All-American Football Team. He received the Phi Beta Kappa key in his junior year, belonged to the Cap & Skull Honor Society, and graduated as Valedictorian. However, it wasn’t until 1995, 19 years after his death, that Paul Robeson was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame.

At Columbia Law School (1919-1923), Robeson met and married Eslanda Cordoza Goode, who was to become the first Black woman to head a pathology laboratory. He took a job with a law firm, but left when a white secretary refused to take his dictation. He left the practice of law to use his artistic talents in theater, film, music and to promote African and African-American history and culture.

Theater and Film

Robeson made a splash in the theater world as the lead in the controversial 1924 production of All God’s Chillun Got Wings in New York City,and the following year, starring in the London production of The Emperor Jones — both by playwright Eugene O’Neill. Robeson also made his first film when he starred in African American director Oscar Micheaux’s 1925 silent film, Body and Soul.

‘Show Boat’ and ‘Ol’ Man River’

Although he was not a cast member of the original Broadway production of Show Boat, Robeson was prominently involved in the 1928 London production. It was there that he first earned renown for singing “Ol’ Man River,” a song destined to become his signature tune.

‘Borderline’, ‘Tales of Manhattan’ and ‘Othello’

In the late 1920s, Robeson and his family relocated to Europe, where he continued to establish himself as an international star through big-screen features such as Borderline (1930).

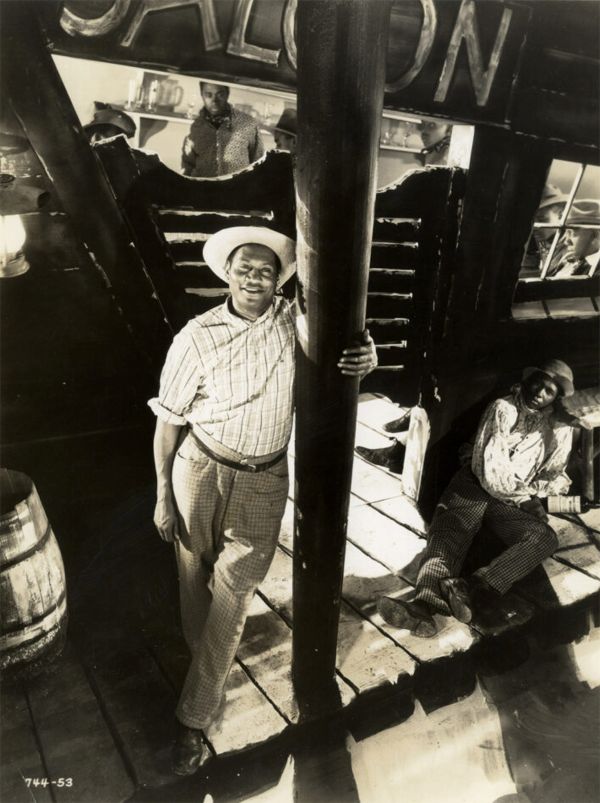

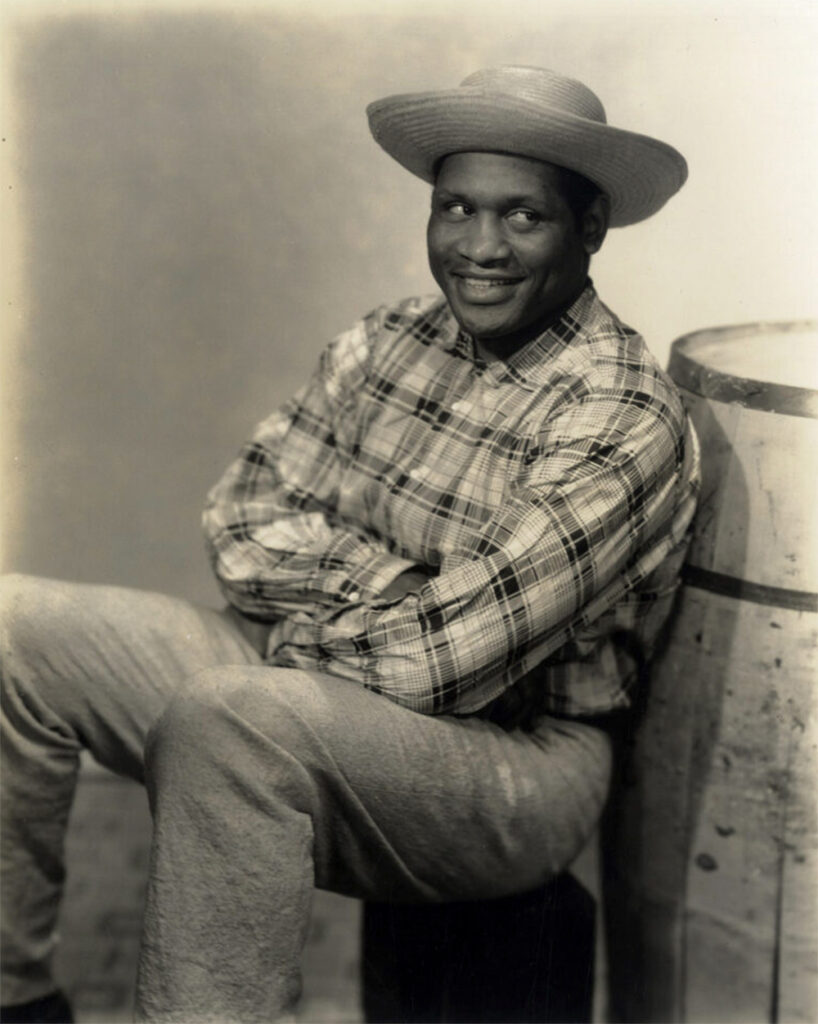

He starred in the 1933 movie remake of The Emperor Jones and would be featured in six British films over the next few years, including the desert drama Jericho and musical Big Fella, both released in 1937. During this period, Robeson also starred in the second big-screen adaptation of Show Boat (1936) (as seen in the two photos above), with Hattie McDaniel and Irene Dunne. Robeson’s last movie would be the Hollywood production of Tales of Manhattan (1942), which also featured legends Henry Fonda, Ethel Waters and Rita Hayworth.

Having first played the title character of Shakespeare‘s Othello in 1930, Robeson again took on the famed role in the Theatre Guild’s 1943-44 production in New York City, for which he won the Donaldson Award for Best Acting Performance. It also starred Uta Hagen, as Desdemona, and José Ferrer, as the villainous Iago. The production ran for 296 performances, the longest-running Shakespeare play in Broadway history

Activism and Song

Robeson’s travels taught him that racism was not as virulent in Europe as in the U.S. At home, it was difficult to find restaurants that would serve him, theaters in New York would only seat Blacks in the upper balconies, and his performances were often surrounded with threats or outright harassment. In London, on the other hand, Robeson’s opening night performance of Emperor Jones brought the audience to its feet with cheers for twelve encores.

Paul Robeson used his deep baritone voice to promote Black spirituals, to share the cultures of other countries, and to benefit the labor and social movements of his time. He sang for peace and justice in 25 languages throughout the U.S., Europe, the Soviet Union, and Africa. Robeson became known as a citizen of the world, equally comfortable with the people of Moscow, Nairobi, and Harlem. Among his friends were future African leader Jomo Kenyatta, India’s Nehru, historian Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, anarchist Emma Goldman, and writers James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway.

In 1933, Robeson donated the proceeds of All God’s Chillun to Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler’s Germany. In New York in 1939, he premiered in Earl Robinson’s Ballad for Americans, a cantata celebrating the multi-ethnic, multi-racial face of America. It was greeted with the largest audience response since Orson Welles’ famous War of the Worlds.

During the 1940s, Robeson continued to perform and to speak out against racism, in support of labor, and for peace. He was a champion of working people and organized labor.

He spoke and performed at strike rallies, conferences, and labor festivals worldwide. As a passionate believer in international cooperation, Robeson protested the growing Cold War and worked tirelessly for friendship and respect between the U.S. and the USSR. In 1945, he headed an organization that challenged President Truman to support an anti-lynching law.

Blacklisting

Because of his outspokenness, he was accused by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) of being a Communist. Robeson saw this as an attack on the democratic rights of everyone who worked for international friendship and for equality. His accusation nearly ended his career.

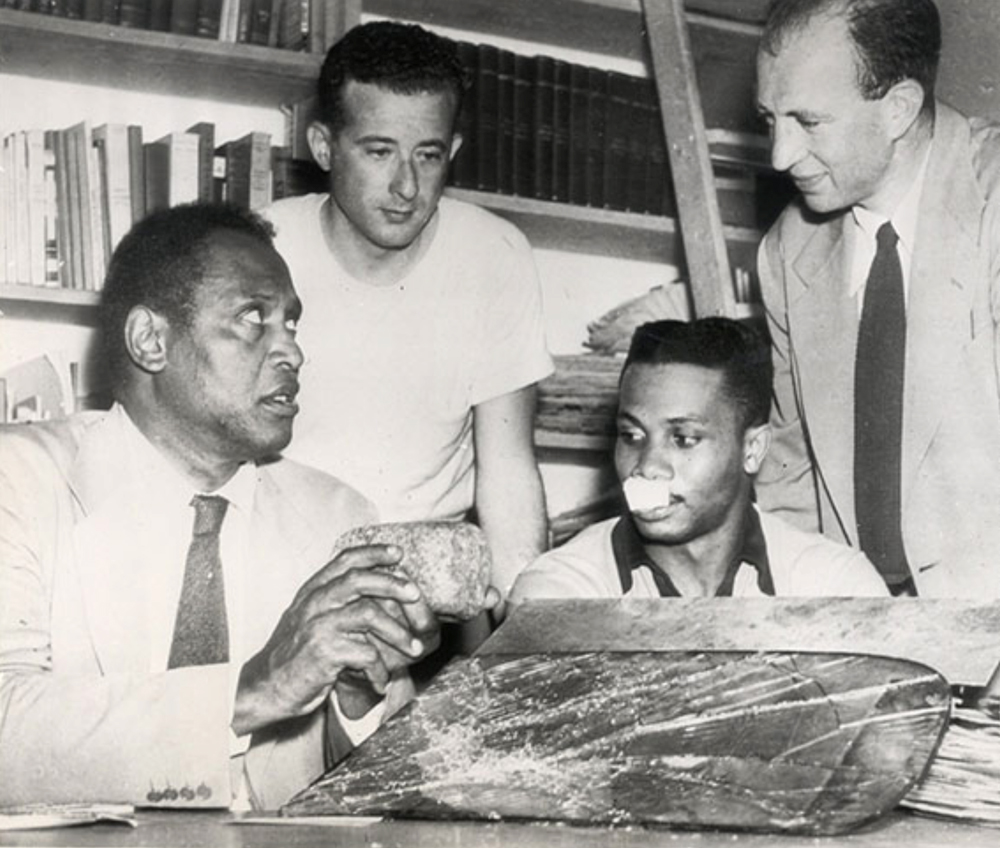

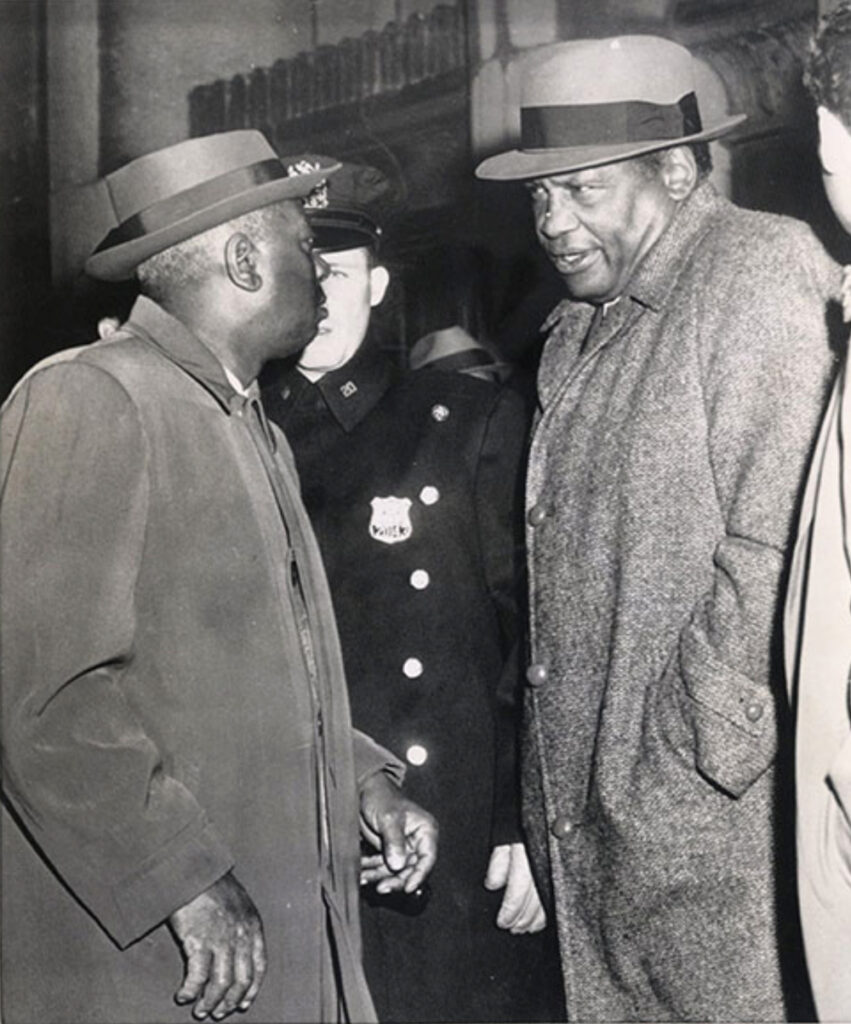

Eighty of his concerts were canceled, and in 1949 two interracial outdoor concerts in Peekskill, N.Y. were attacked by racist mobs while state police stood by. Robeson responded, “I’m going to sing wherever the people want me to sing…and I won’t be frightened by crosses burning in Peekskill or anywhere else.”

In 1950, the U.S. revoked Robeson’s passport, leading to an eight-year battle to resecure it and to travel again. During those years, Robeson studied Chinese, met with Albert Einstein to discuss the prospects for world peace, published his autobiography, Here I Stand, and sang at Carnegie Hall.

Later Years, Book & Death

Robeson published his autobiography, Here I Stand, in 1958, the same year that he won the right to have his passport reinstated. He again traveled internationally and received a number of accolades for his work, but damage had been done, as he experienced debilitating depression and related health problems.

Robeson and his family returned to the United States in 1963. After Eslanda’s death in 1965, he lived with his sister. He died from a stroke on January 23, 1976, at the age of 77, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Paul Robeson’s Legacy

In recent years, efforts have been made by various industries to recognize Robeson’s legacy. Several biographies have been written on the artist, including Martin Duberman’s well-received Paul Robeson: A Biography, and he was inducted posthumously into the College Football Hall of Fame. In 2007, Criterion released Paul Robeson: Portraits of the Artist, a box set containing several of his films, as well as a documentary and booklet on his life. Reference: Biography, Wikipedia

View More Of Paul Robeson

- African American Movie Memorabilia

- African Americana

- Black History

- Celebrating Women’s HistoryI Film

- Celebrity Photographs

- Current Exhibit

- Famous Female Vocalists

- Famous Hollywood Portrait Photographers

- Featured

- Film & Movie Star Photographs

- Film Noir

- Film Scripts

- Hollywood History

- Jazz Singers & Musicians

- LGBTQ Cultural History

- LGBTQ Theater History

- Lobby Cards

- Movie Memorabilia

- Movie Posters

- New York Book Fair

- Pressbooks

- Scene Stills

- Star Power

- Vintage Original Horror Film Photographs

- Vintage Original Movie Scripts & Books

- Vintage Original Publicity Photographs

- Vintage Original Studio Photographs

- WalterFilm