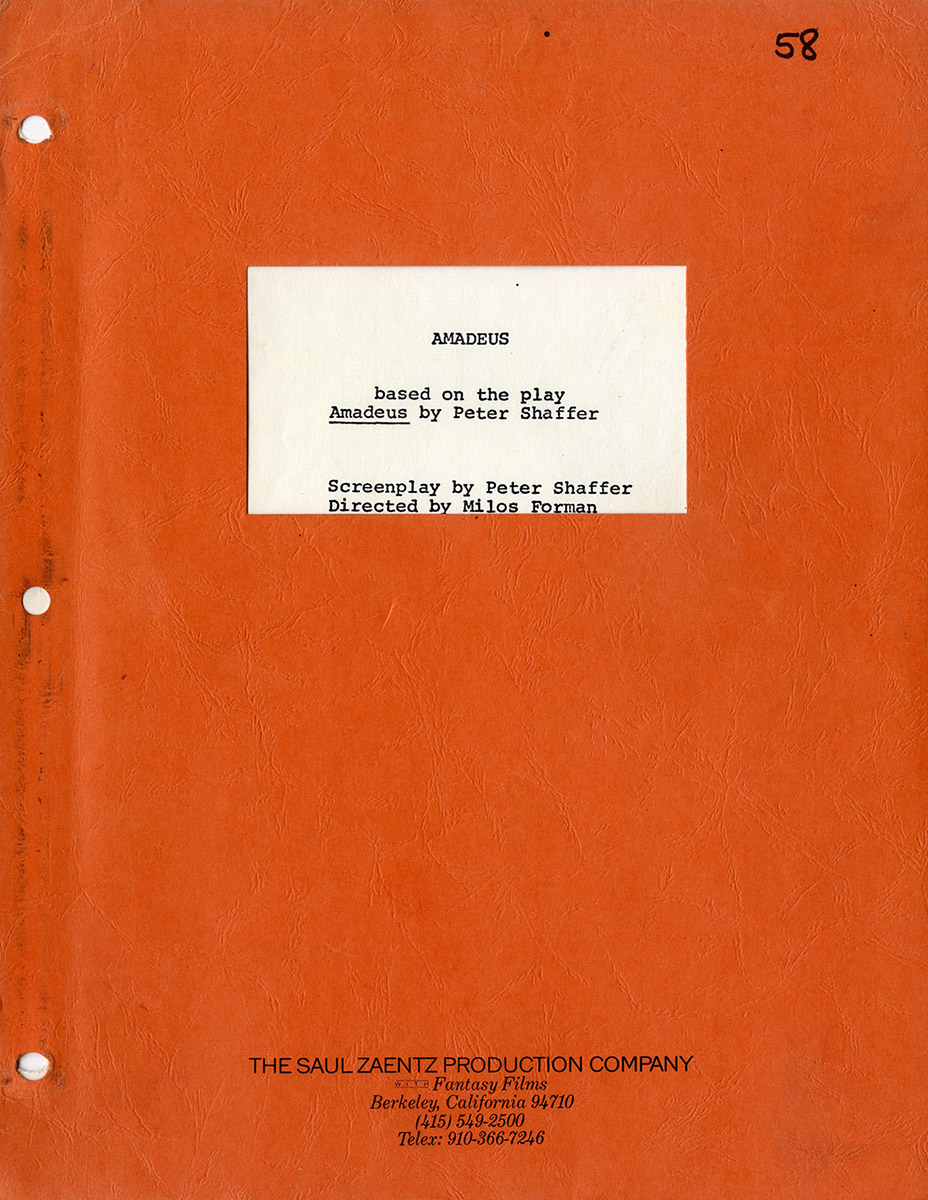

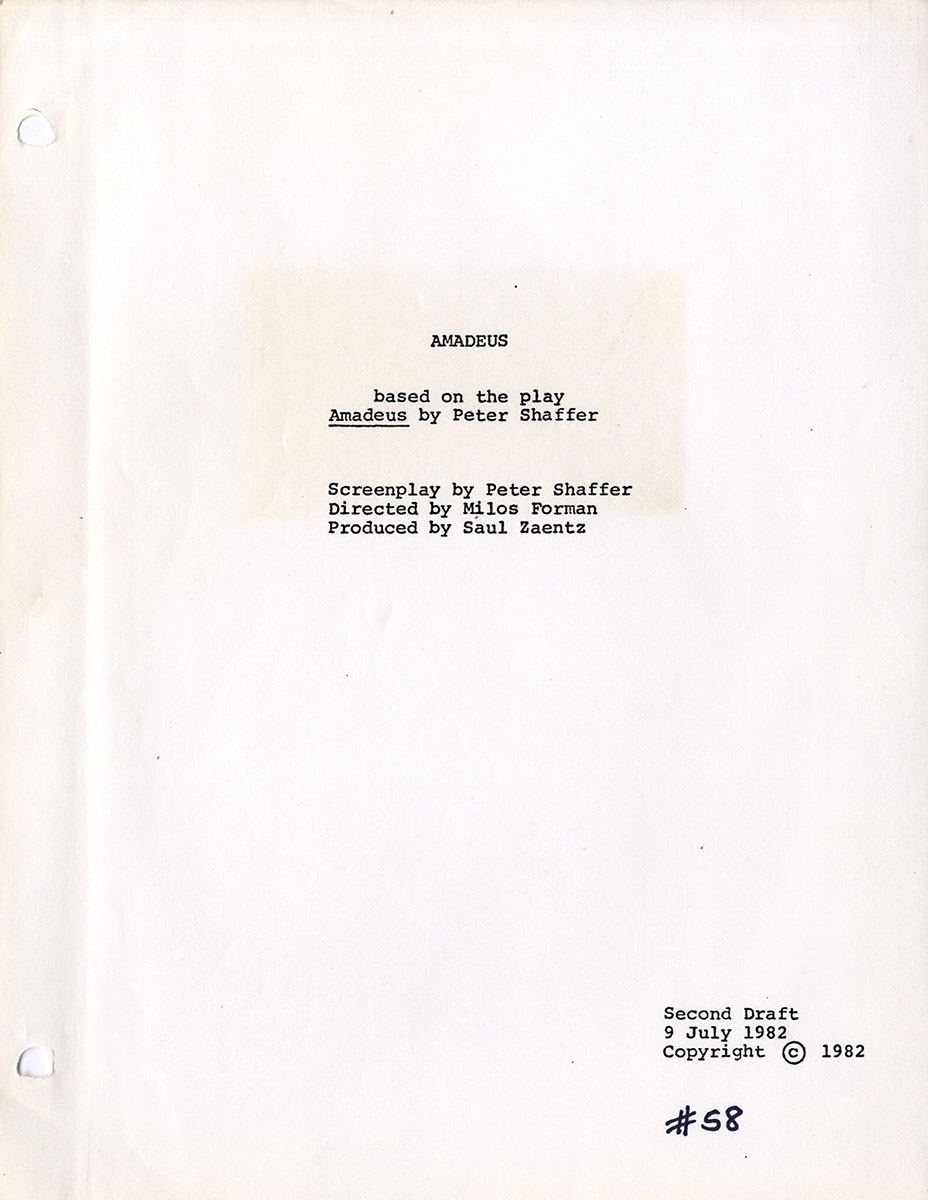

AMADEUS (Jul 9, 1982) Second Draft screenplay by Peter Shaffer

Berkeley, CA: Saul Zaentz Production Company, 1982. Vintage original film script, bound with a metal clasp. Printed wrappers with a die-cut window, 11 x 8 ½” (28 x 22 cm.), 148 pp., just about fine.

According to Czech film director Miloš Forman (1932-2018), he first encountered Peter Shaffer’s play AMADEUS during its initial London theatrical run. At the end of the First Act, Forman went backstage and told author Shaffer that if the rest of the play was as good as the First Act, he was going to make a movie of it. Forman was not disappointed. Shortly thereafter, he called producer Saul Zaentz with whom he had made the Academy Award-winning ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST (1975), and the rest is cinematic history.

AMADEUS is one of the most honored films of all time. It earned a total of eight Academy Awards for the year 1984, including Best Picture, Best Director (Forman), Best Adapted Screenplay (Shaffer), Best Actor (F. Murray Abraham as Salieri), Best Art Direction, Best Costume Design, Best Makeup, and Best Sound. It also earned four BAFTA Awards, four Golden Globe Awards, a Directors Guild of America award, and in 1998, the American Film Institute ranked it 53rd on its “100 Years… 100 Movies” list.

The film is a happy confluence of two major auteurs, Shaffer and Forman, fully expressing the most personal themes of each. For playwright Peter Shaffer (1926-2019), AMADEUS embodies his recurring theme of one man’s obsessive envy for another whom the former believes to have been touched by the Divine. In the case of Shaffer’s THE ROYAL HUNT OF THE SUN (London premiere, 1964), it was the Spanish conquistador Pizarro’s envy of the Incan Prince Atahualpa who considered himself the son of the Sun god. In EQUUS (London premiere, 1973), it was a psychiatrist’s envy of a young patient who worships horses. In AMADEUS (London premiere, 1979), it was the comparatively obscure composer Salieri’s envy of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (played in the film by Tom Hulce), the “obscene child” in whose music Salieri hears the “voice of God.”

For director Forman, Mozart was the archetypal protagonist who appears in virtually all of his best films, eccentric anti-authoritarian misfits like McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) in ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST (1975), Evelyn Nesbit and Coalhouse Walker in RAGTIME (1981), Larry Flynt in THE PEOPLE VS. LARRY FLYNT (1996), and Andy Kaufman in MAN ON THE MOON (1999).

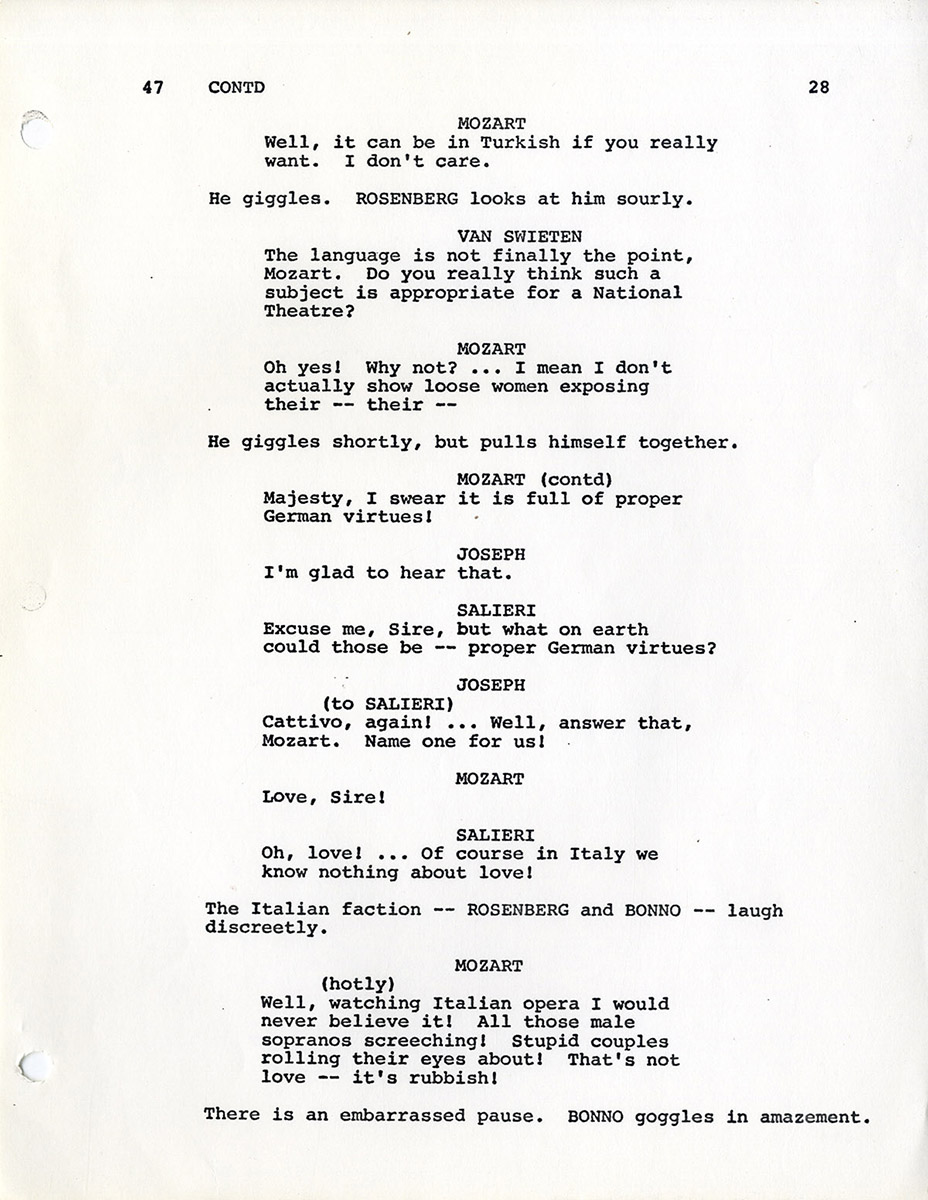

Shaffer and Forman spent four months together reimagining Shaffer’s play as a motion picture, and there were many changes that occurred during the adaptation process. For Forman, the key was, “More Mozart, more music.” The creators agreed that where the play had two principal characters, Salieri and Mozart, the movie would have three, Salieri, Mozart, and Mozart’s music — the substantial excerpts from his operas and concert works that are seen and heard throughout the film. Where the play was highly theatrical — abstract and Brechtian in its presentation — the movie is a naturalistic period piece with lush, historically detailed costumes and sets.

Where in the play, Salieri narrates his story directly to the theater audience, in the movie, he tells his story to a young priest who has come to hear the old man’s confession. The drama was never meant to be historically accurate — Salieri was not, in fact, responsible for Mozart’s death — but rather, in Shaffer’s words, a “fantasia on the theme of Mozart and Salieri.”

The film script also employs a number of devices that are unique to motion pictures, such as the Griffith-like cross-cutting between Salieri and the dying Mozart completing the composition of Mozart’s Requiem Mass, intercut with Mozart’s wife, Constanze (Elizabeth Berridge), rushing home from Salzburg via carriage to reunite with her husband in Vienna.

Shaffer’s Second Draft screenplay is fairly close to what was ultimately filmed, but clearly tweaked and polished to a significant degree before shooting began. Interestingly, a number of scenes that were shot but omitted from the initial 1984 release were restored to the 2002 Director’s Cut, increasing the film’s length from 161 minutes to three hours.

Among the changes — in the Second Draft screenplay version of the scene where Salieri first encounters Mozart, covertly watching as Mozart pursues little Constanze under a table, Mozart playfully talks backwards to the girl with vulgar phrases like “Sar-i’m-kil” (“Lick my arse”) and “Tish-i’m-tea” (“Eat my sh*t”). Significantly, to make Mozart more sympathetic in this scene, the movie adds two more phrases to his backwards-talking game, “I love you” and “Will you marry me.”

Another significant change occurs in a following scene where Salieri reads “in helpless fascination” Mozart’s score for his “Sinfonia Concertante.” In the movie, we not only hear Mozart’s “Sinfonia Concertante” on the soundtrack, but a monologue beautifully written by Shaffer in which Salieri analyzes the music as we hear it played.

Many scenes are elaborated in the movie with bits of business, for example, in both the script and the film when Mozart is being scolded by his patron, the Archbishop, for being late to the performance of his “Sinfonia Concertante,” Mozart opens the door of the chamber so that the Archbishop can see the audience outside applauding the composer. In the movie, however, this is staged so that as Mozart bows to the audience, he presents his rear to the Archbishop.

Constanze comes across much more sympathetically in the movie than she does in the screenplay — this appears to be largely a matter of casting and direction; one suspects that Forman likes women more than Shaffer did.

Other scenes are less elaborate in the film than in the screenplay, for example, the scene where Mozart, Constanze, and Mozart’s father attend a masquerade ball — in the screenplay, this scene contains a prolonged sequence involving the exchanging of costumes and wigs which is omitted from the completed film.

The hospital in the screenplay where Old Salieri tells his story becomes in the film a grotesque madhouse like a 19th century version of the asylum in ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST. It is here that Salieri bestows his final benediction on all the mediocrities in the world like himself who were not blessed with Mozart’s genius:

OLD SALIERI

Mediocrities everywhere — now and to come — I absolve you all! . . .Amen! . . . Amen! . . . Amen!

Out of stock

Related products

-

Mark Twain (source) LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI (ca. 1956) TV script adapted by William Robert Yates

$300.00 Add to cart -

![LES CREATURES [THE CREATURES] (1966) French film script](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/LesCreaturesSCR_a-540x689.jpg)

Agnès Varda (screenwriter, director) LES CRÉATURES (1966) Film script

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart -

LONG WALK HOME, THE (Oct 13, 1988) Second draft film script by John Cork

$375.00 Add to cart