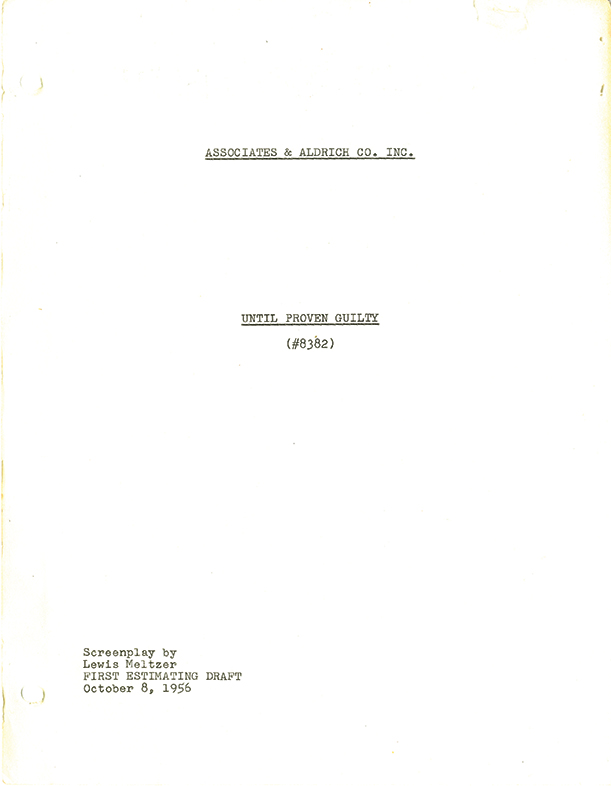

UNTIL PROVEN GUILTY (Oct 9, 1956) Unproduced screenplay for Robert Aldrich production

First Estimating Script, Los Angeles: Columbia Pictures, October 9, 1956. Vintage original film script, quarto, mimeograph, brad bound, 130 pp., some wear to edges of front wrapper and blank tops of preliminary leaves, very good+.

An unproduced screenplay directly relevant to the politics of the McCarthy Era, intended for Robert Aldrich to direct. It was normal for him to directly participate in the writing of scripts for his films, and it is highly likely that he was involved in this one, as usual.

Associates & Aldrich was a production company set up by director Robert Aldrich (1918-1983) following the success of the two Burt Lancaster Westerns he directed for Hecht-Lancaster Productions, APACHE and VERA CRUZ (both 1954). In its first two years, Associates & Aldrich produced three films that are considered among director Aldrich’s finest, KISS ME DEADLY (1955), THE BIG KNIFE (1955), and ATTACK! (1956). During this same period, Aldrich commissioned and worked on screenplays for several other projects that were never actually produced, including this 1956 screenplay, UNTIL PROVEN GUILTY, by Lewis Meltzer.

Lewis Meltzer (1911-1995) was a playwright and screenwriter who first came to Hollywood in 1938. His many screen credits include THE TUTTLES OF TAHITI (1944), COMMANCHE TERRITORY (1950), ALONG THE GREAT DIVIDE (1951), THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM (1956), and HIGH SCHOOL CONFIDENTIAL (1958). He had previously collaborated with director Aldrich on the noirish Joan Crawford melodrama, AUTUMN LEAVES (1956).

According to Alain Silver and James Ursini in their book, Whatever Happened to Robert Aldrich?: His Life and Films (Limelight, 1995):

UNTIL PROVEN GUILTY [was] the story of a teacher unjustly accused of raping a 14-year-old student based on the play, “Storm in the Sun”, by Fern Mosk and Anne Taylor. This project was developed for Columbia with draft scripts by Lewis Meltzer and Oscar Millard, and Aldrich approached Olivia de Havilland about starring. Columbia rejected the script as too controversial and rescinded their contract with Aldrich in March for “failure to revise the screenplay in accordance with our suggestion and…work cooperatively”. Aldrich quickly sued and settled when Columbia agreed to pay all costs, but the project was never revived.

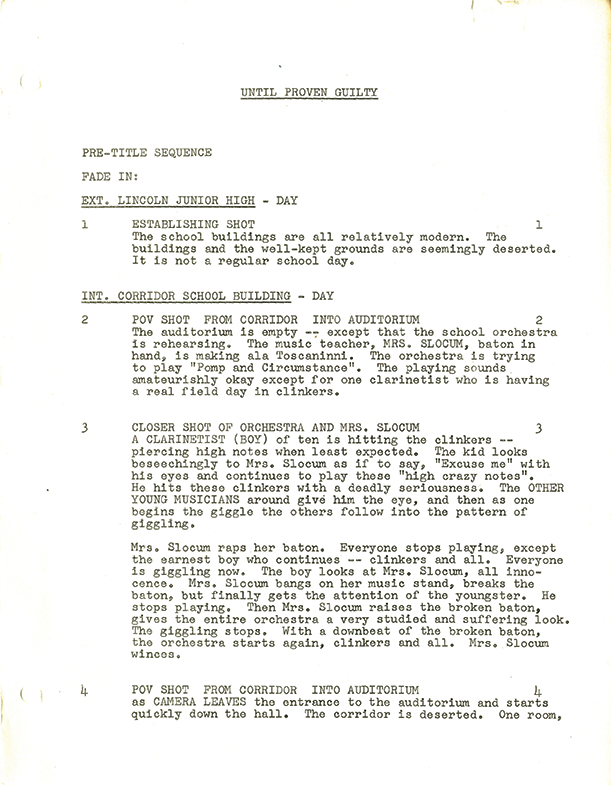

Meltzer’s screenplay begins with a music teacher rehearsing a high school orchestra. Outside the auditorium, the camera tracks down a corridor to a door where we hear the sounds of a struggle, then the outcry of a young girl:

The door is suddenly opened. CYNTHIA OSBORNE, a young girl of fourteen, well-developed and pretty, comes out of the office . . . . CAMERA MOVES in as SAM MASON appears in the doorway.

Sam Mason is the social studies teacher who will be accused of “attacking” the girl. What is striking about this opening, the first several pages of the script up to and beyond the opening credits, is that it is all visual storytelling – no dialogue. The screenplay reads like a final shooting script, ready to be filmed tomorrow.

UNTIL PROVEN GUILTY – even more so than Aldrich’s KISS ME DEADLY – is a product of the 1950s McCarthy Era, an era when mere accusations of communist sympathies were enough to prove an accused person guilty (at least, for purposes of the Hollywood blacklist). After the screenplay’s credit sequence, we are introduced to the Breeze Family, Roger, the school principal, Nan, his wife, and their teen daughter, Polly, who are expecting their teacher friend Sam Mason to join them for breakfast. Nan, as it happens, is a novice lawyer. They learn of Sam’s arrest.

Nan is confronted by a newspaper gossip columnist who points out that in addition to allegedly “molesting a minor“, Sam has shown a “naughty movie” to “those little girls and boys in his classroom“. Nan the lawyer responds that, “The picture is called ‘The Story of Human Reproduction’ made by the Biology Department of the University. It’s being used in Elementary and High Schools in some twenty-five states throughout the country“. The gossip columnist decisively adds, “He never goes to church …“. In the meantime, Roger, the principal, has to deal with a school board member who objects to his “little flurries in modern teaching techniques” and interest in “progressive methods“. He is told that if he testifies on behalf of his friend, Sam, it will look bad for the school and he will probably lose his job. Roger is angered when he learns that Nan has posted bail for Sam using the family’s credit, and the situation is worsened when Sam apparently jumps bail. Nan is dumbfounded when her law firm boss, Reiner, declines to defend Sam.

REINER

I’m all in favor of justice. But I have no desire to commit professional suicide. . . . In two months’ time my practice would be limited to traffic violators.

Sam reappears (he didn’t leave town, he has been hiding out, sleeping in his car) and confesses to Jan the real story – which we see onscreen as he talks. The student, Cynthia, confronted him in a classroom and begged him not to graduate her, “She wanted me to keep her back, so she could stay near me … said she loved me … couldn’t live without me …“, kissing him forcefully on the mouth. When Sam rebuffed her, she became infuriated and started beating him with her fists. Witnesses to the aftermath of the incident only saw the agitated girl running from the classroom and the lipstick on Sam’s face. Nan agrees to take Sam’s case.

There is a trial, and Nan does her best to win, not by putting Sam or his alleged victim on the stand, but by undercutting the testimony of the witnesses, exposing their prejudices and hypocrisy, and by giving a brilliant summation. Regardless, Sam is found guilty. Nan’s boss, Reiner, shows up at Nan and Roger’s house afterwards, regretting he did not try the case himself and explaining:

REINER

A, I’m loaded. B, the verdict’ll never stand up. No question that Nan will win on appeal. The judge’s hostility was a thing of beauty – and a matter of record. B or C – it doesn’t matter. Long after Nan’s won her appeal – this town will stand convicted of bigotry! That’s for sure!

Like many of Robert Aldrich’s projects from this era, this unproduced screenplay is an indictment of 1950s America, finding the defendant guilty as charged.

Out of stock