Robert Altman (director) MASH (Feb 26, 1969) Final draft screenplay by Ring Lardner Jr.

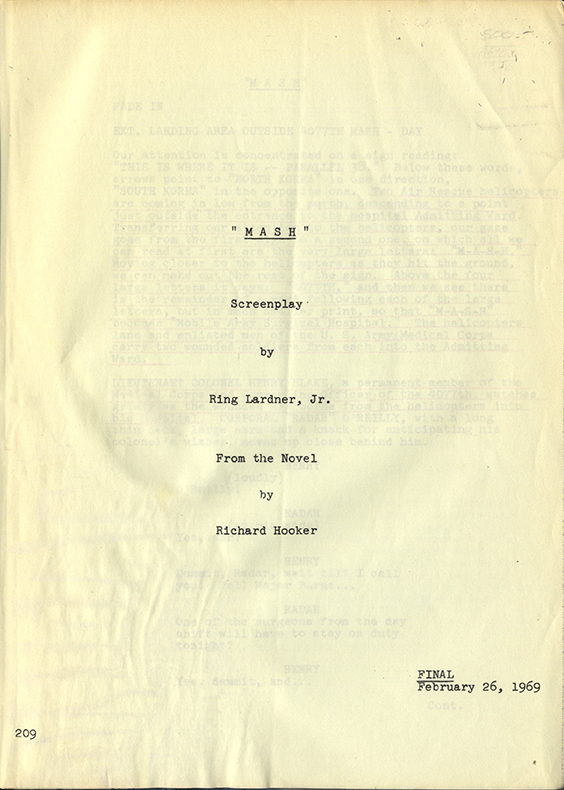

Screenplay by Ring Lardner, Jr. February 26, 1969. Vintage original film script. [1],141 leaves. Quarto. Mimeographed typescript, brad bound in printed studio wrappers. Ink name on upper wrapper, wrappers show a faint damp/spill discoloration in from the spine in the lower quadrant, title leaf slightly rippled (but not stained) in same area, wrappers a bit creased and snagged at overlap edges, a few marginal paper clip marks and a few passages neatly underscored in red ink, otherwise very good.

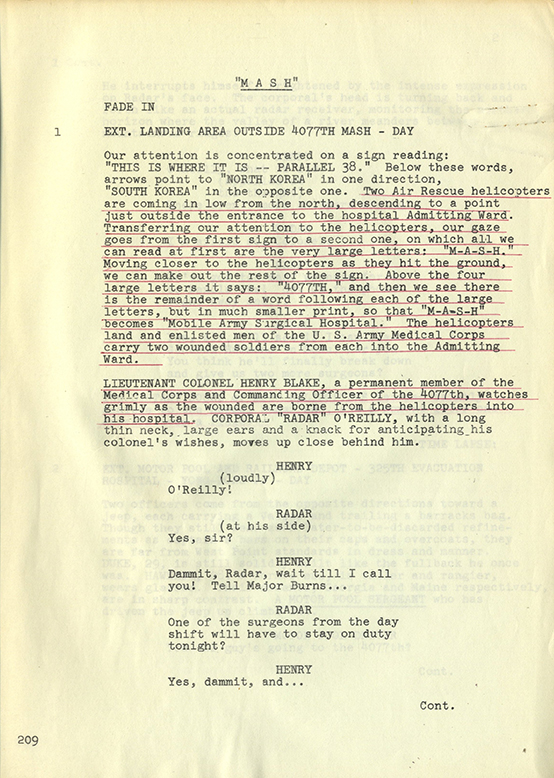

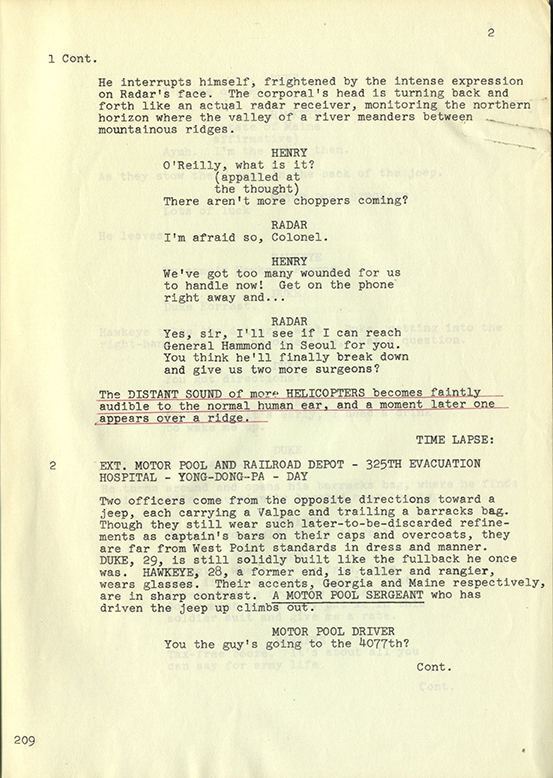

Denoted a “Final” draft of the screenplay for Lardner’s adaptation of Hooker’s novel, one of the seminal films of its era, and though set in Korea, one of the handful of on-target critiques of the Vietnam war released by a Hollywood studio. A cursory examination of the script indicates that significant changes were yet to be made between the version represented by this draft and the film that saw release in January of 1970, under the direction of Robert Altman, starring Donald Sutherland, Elliott Gould, Robert Duvall, Sally Kellerman, Tom Skerritt, Gary Brughoff, et al. It was also one of Lardner’s post Black List triumphs, for which he won an Academy Award. The ownership signature is of one “Bob Burkhart,” and although he does not appear in the screen credits, the underlined passages relate chiefly to scenes involving helicopters, and he may have been associated with that element of the production.

Screenwriter Ring Lardner, Jr. (1915-2000) served a year in prison as one of the original Hollywood Ten. He wrote or co-wrote the screenplays of George Stevens’ WOMAN OF THE YEAR, Fritz Lang’s CLOAK AND DAGGER, Otto Preminger’s FOREVER AMBER, Joseph Losey’s THE BIG NIGHT (uncredited due to being blacklisted), and Norman Jewison’s THE CINCINNATTI KID, among many others. He was honored with an Academy Award for his screenplay of MASH. (The acronym, MASH, stands for Mobile Army Surgical Hospital.)

Yet, according to MASH’s director, Robert Altman, Lardner was unhappy with Altman’s direction of Lardner’s screenplay, because the director didn’t use enough of the writer’s “words.”

This was due to Altman’s unusual way of working, in which the actors, while adhering to a written scene’s basic structure, were given free rein to improvise their own dialogue and business, and even allowed to overlap each other’s lines. As part of Altman’s singular approach, he de-emphasized the roles of the stars (in this case, Donald Sutherland and Elliot Gould), filling his ensemble with trained theater actors who’d never appeared in a movie before, and treating each member of the large ensemble cast as a fully developed character – there are no true “extras” in an Altman movie. Altman’s attention to the background players so dismayed the stars, Sutherland and Gould, that they attempted to have the director fired. (Gould later apologized. Sutherland did not.)

Although the story was supposed to take place during the 1950s Korean War, Altman did everything he could to make the action seem contemporary, i.e., reflective of the Vietnam War that was taking place while MASH was being shot. Another memorable aspect of the film, the frequent – often absurd – announcements on the camp’s loudspeaker system, was something conceived and added during the editing process.

Nevertheless, Altman’s film is quite faithful to the structure and irreverent spirit of Lardner’s screenplay. The movie’s most innovative and critically acclaimed idea, the alternation of comic scenes with the grim reality of the military operating theater, comes straight out of Lardner’s screenplay in which the effect of the bloodied casualties “viewed individually and at close range … is almost unbearable.” The Christian hypocrite, Frank Burns, played by Robert Duvall in the film, is fully created in Lardner’s script. Though not all of the film’s dialogue was written by Lardner, most of its best lines were.

The scenes involving “Painless” the dentist, who wants to commit suicide due to (temporary) impotence, and the way the MASH ensemble cures him, are all in Lardner’s screenplay. Yet it was Altman’s idea, conceived on the day of shooting, to arrange the actors around the dentist in a composition echoing Da Vinci’s “Last Supper.” The lyrics to the song, “Suicide is Painless,” that is sung during this sequence were written by Altman’s 14-year-old son.

A 21st century reader – or viewer – of MASH might be struck by the rampant sexism of both the screenplay and the film that was made from it. Director Altman in his audio commentary acknowledges this aspect of the project, and excuses it, at least in part, by explaining this was the way women were actually treated in the military during the wars in Korea and Vietnam. In this context, we should note that one of MASH’s most cringe-inducing episodes, the humiliating exposure of “Hot Lips” Houlihan (Sally Kellerman) in the nurses’ shower, is filmed almost exactly as described in Lardner’s screenplay. On the other hand, the MASH screenplay’s treatment of military racism is fairly progressive for its time. A sentimental episode involving the death of the camp’s Korean boy, Ho-Jon, is omitted from the completed film. Likewise, the ending of Altman’s film is more ambivalent and anti-climactic – has far less of a sense of closure – than the conclusion of Lardner’s screenplay, most likely because the Vietnam War, the film’s real subject, was still going on.

MASH was a huge hit for the studio that released it, 20th Century Fox, because, like BONNIE AND CLYDE or THE GRADUATE, it mirrored the anti-establishment attitudes of its era. Altman would return to the theme of smart-ass college boys versus career military personnel in his underrated television adaptation of THE CAINE MUTINY COURT MARTIAL (1988), only in the latter film Altman’s sympathies clearly lay with the career men. It isn’t that Altman became more conservative in his later years. It would be more accurate to say that as Altman matured, he was more inclined to look at a situation from every side. THE CAINE MUTINY COURT MARTIAL is in a sense Altman’s apologia for MASH, the landmark film that made his reputation to begin with.

Out of stock