TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD (1962) Archive of 3 film scripts

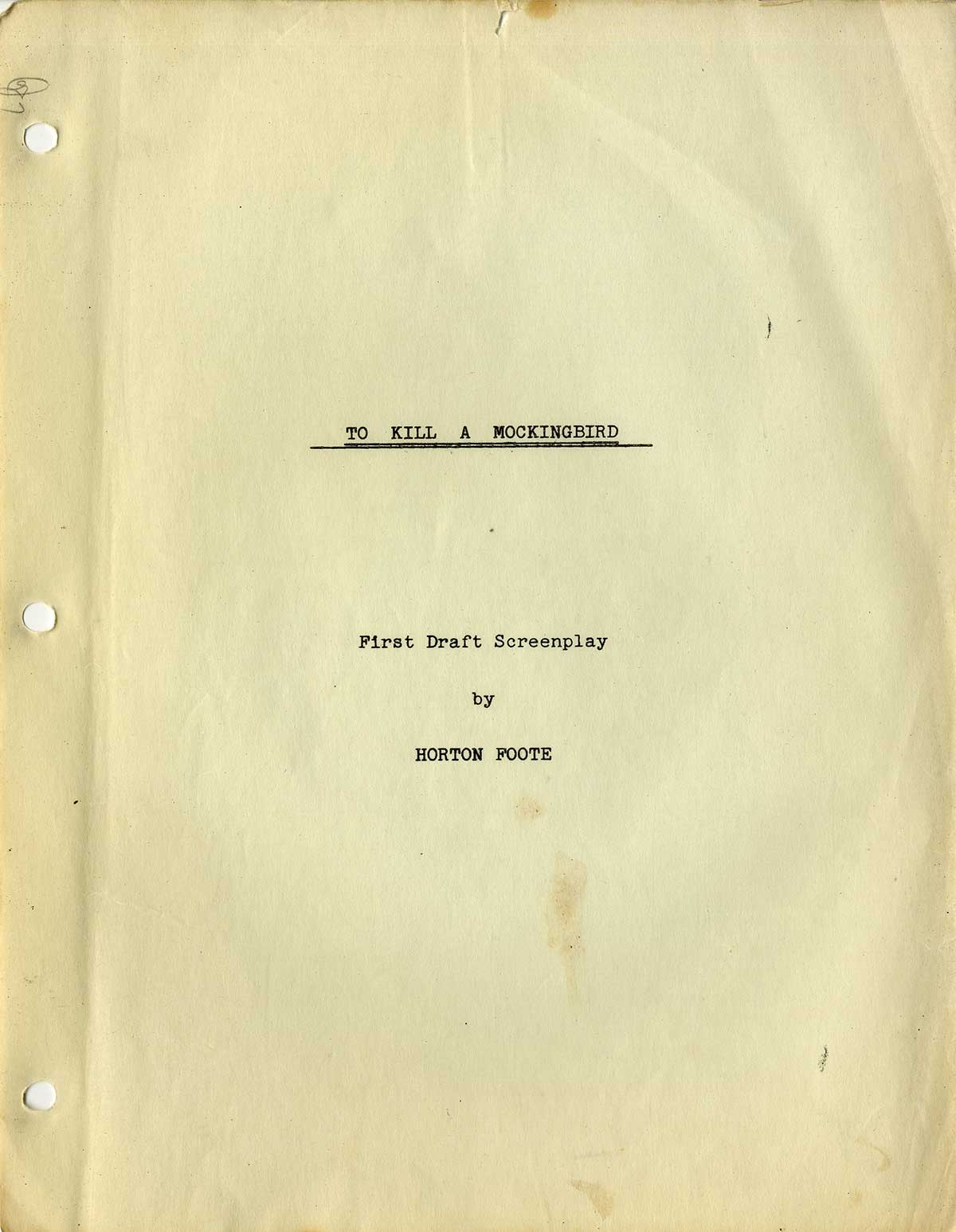

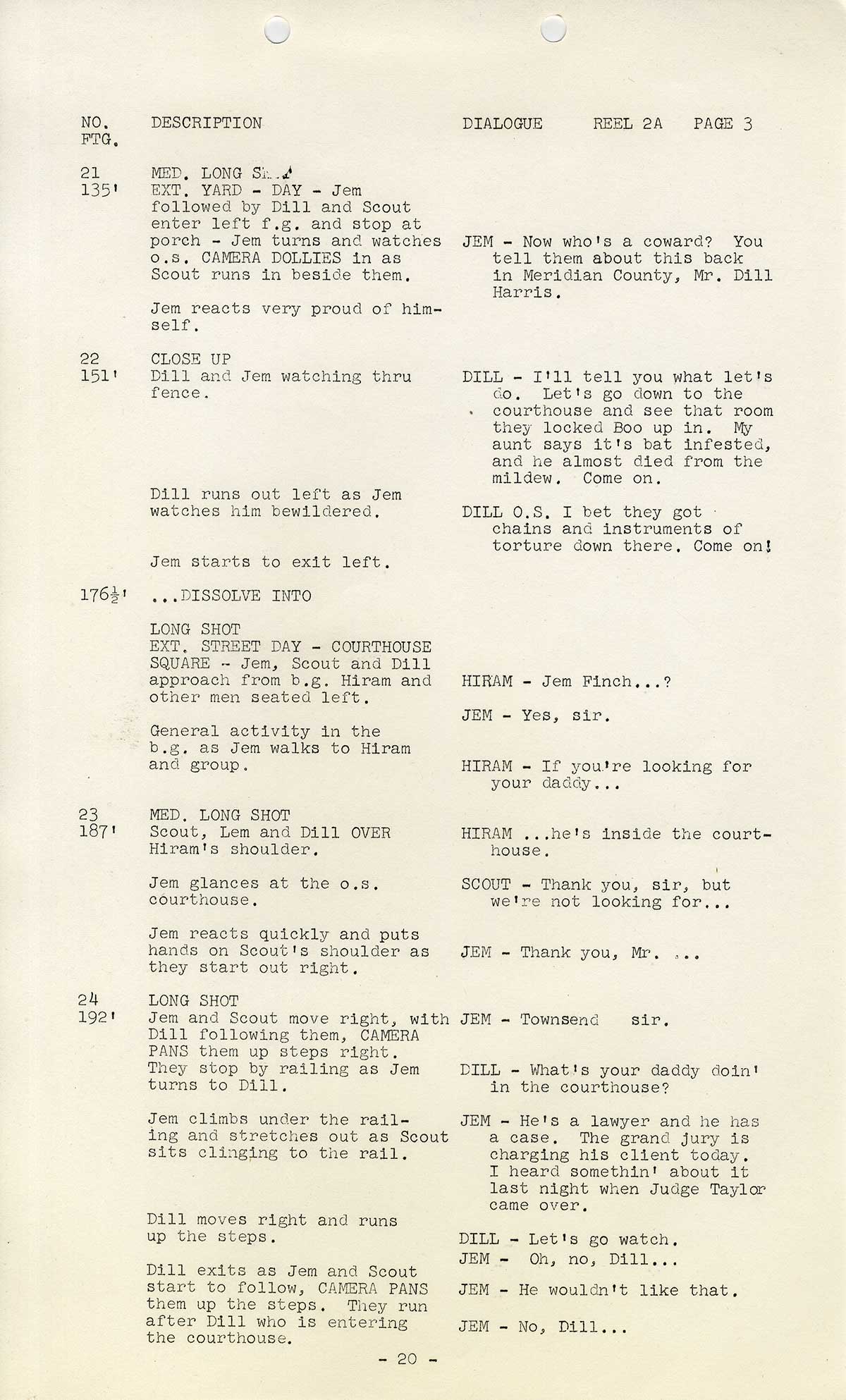

Harper Lee (source), Horton Foote (screenwriter) An archive of three (3) vintage original film scripts, Hollywood, Universal City, 1961-1962.

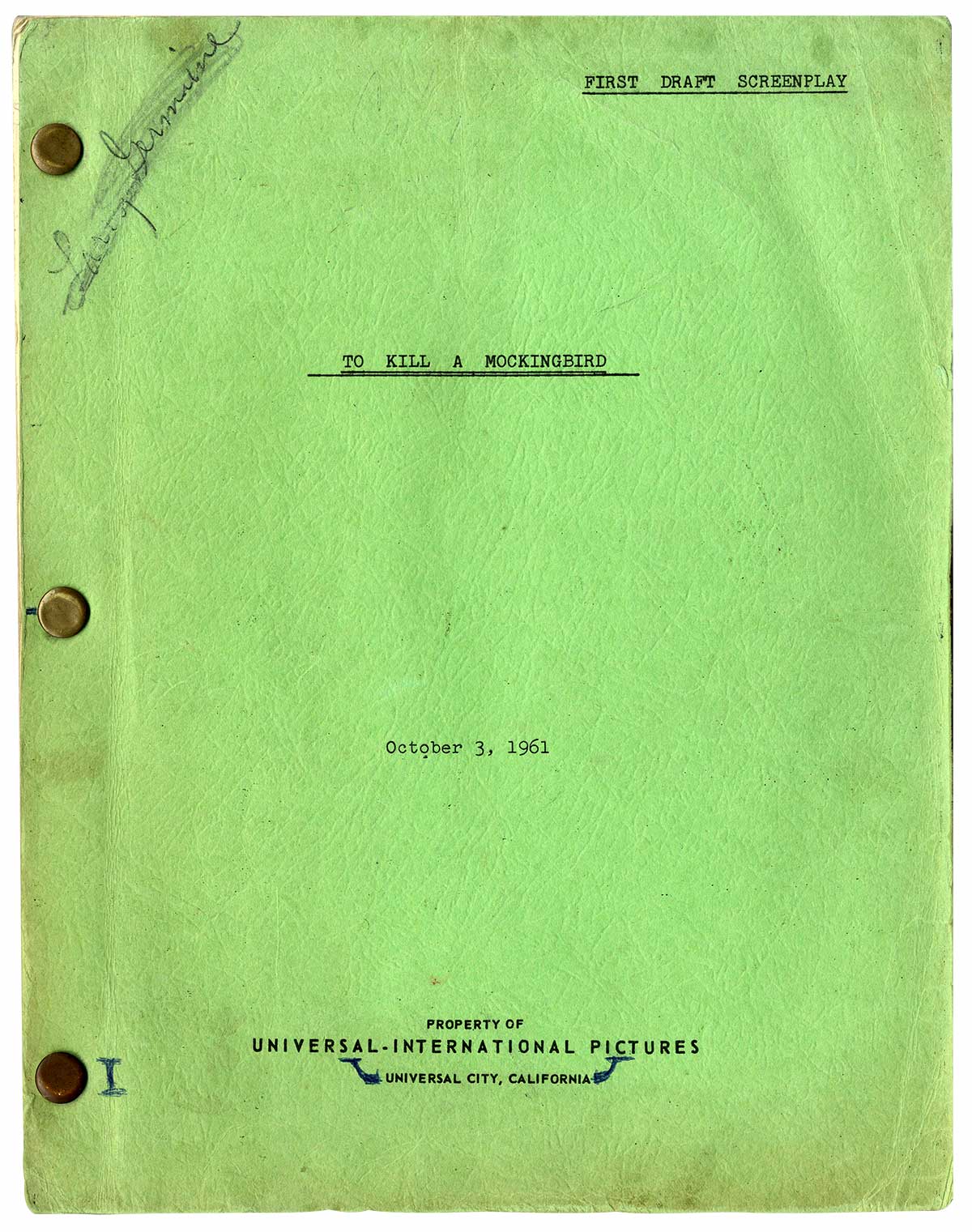

- First Draft Screenplay by Horton Foote dated October 3, 1961. Printed wrappers, brad bound, quarto, mimeograph, 157 pp. A few markings on front cover, generally NEAR FINE in VERY GOOD+ covers. This particular script apparently belonged to Larry Germain, who was the film’s hair stylist. It does not have any annotations in his hand.

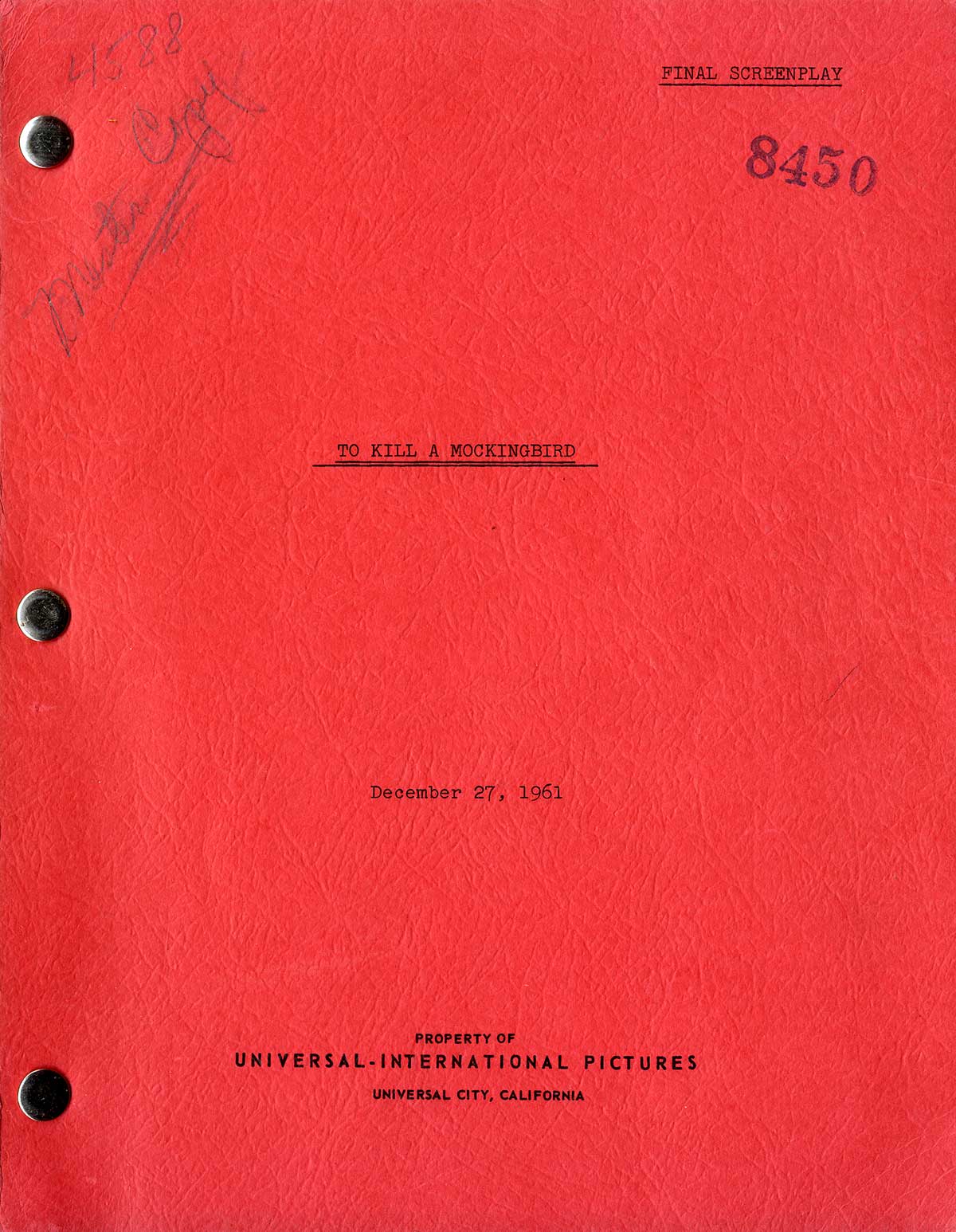

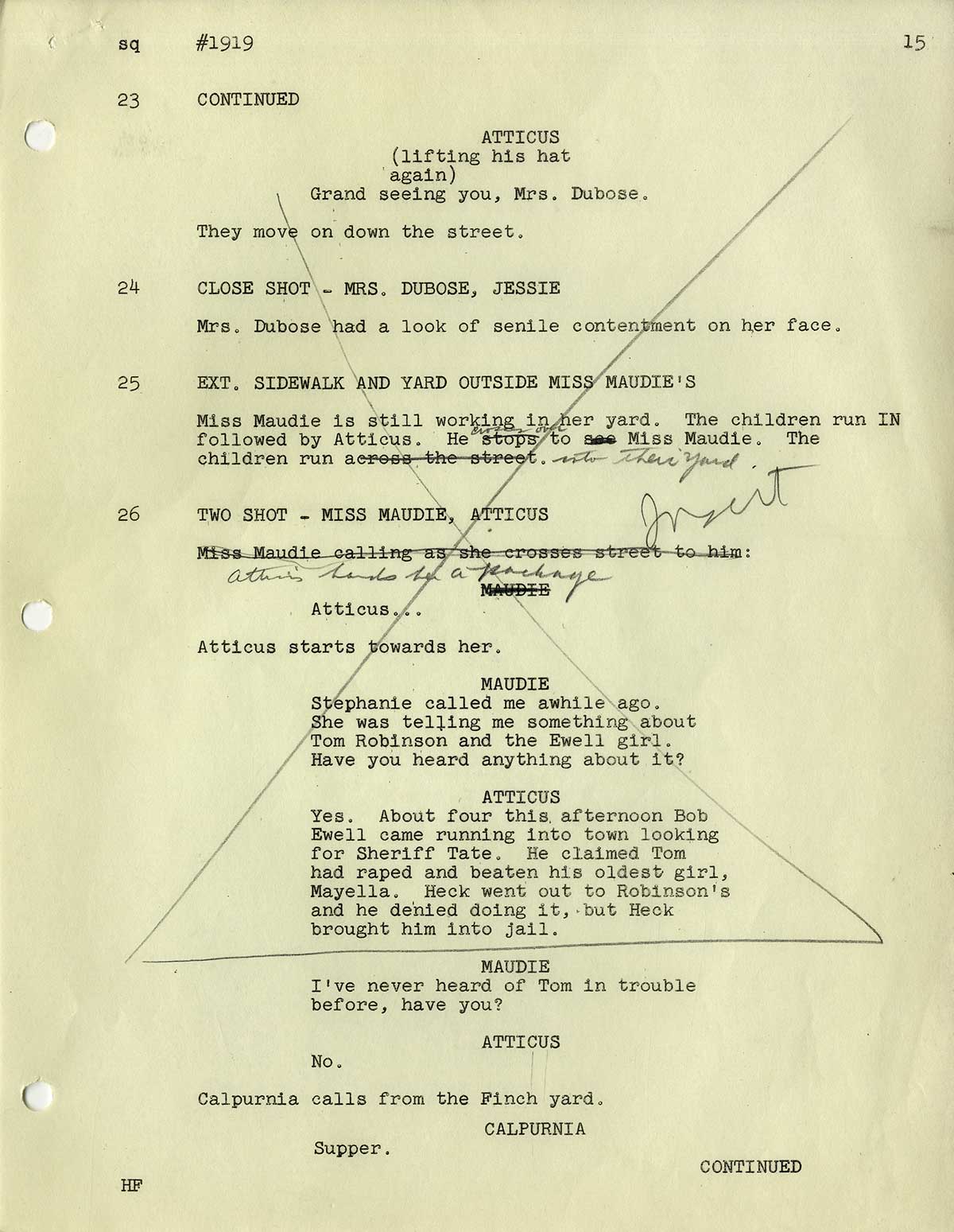

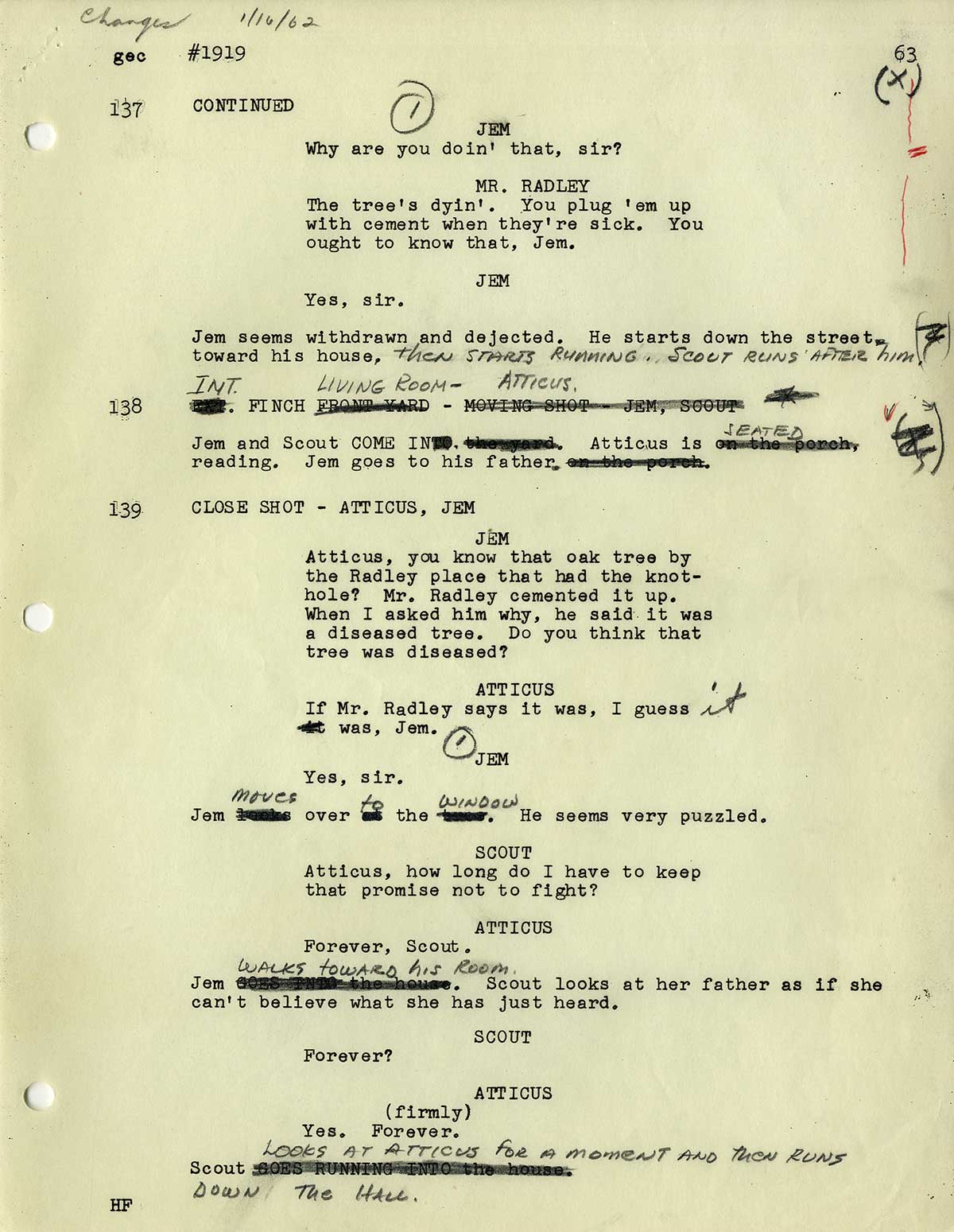

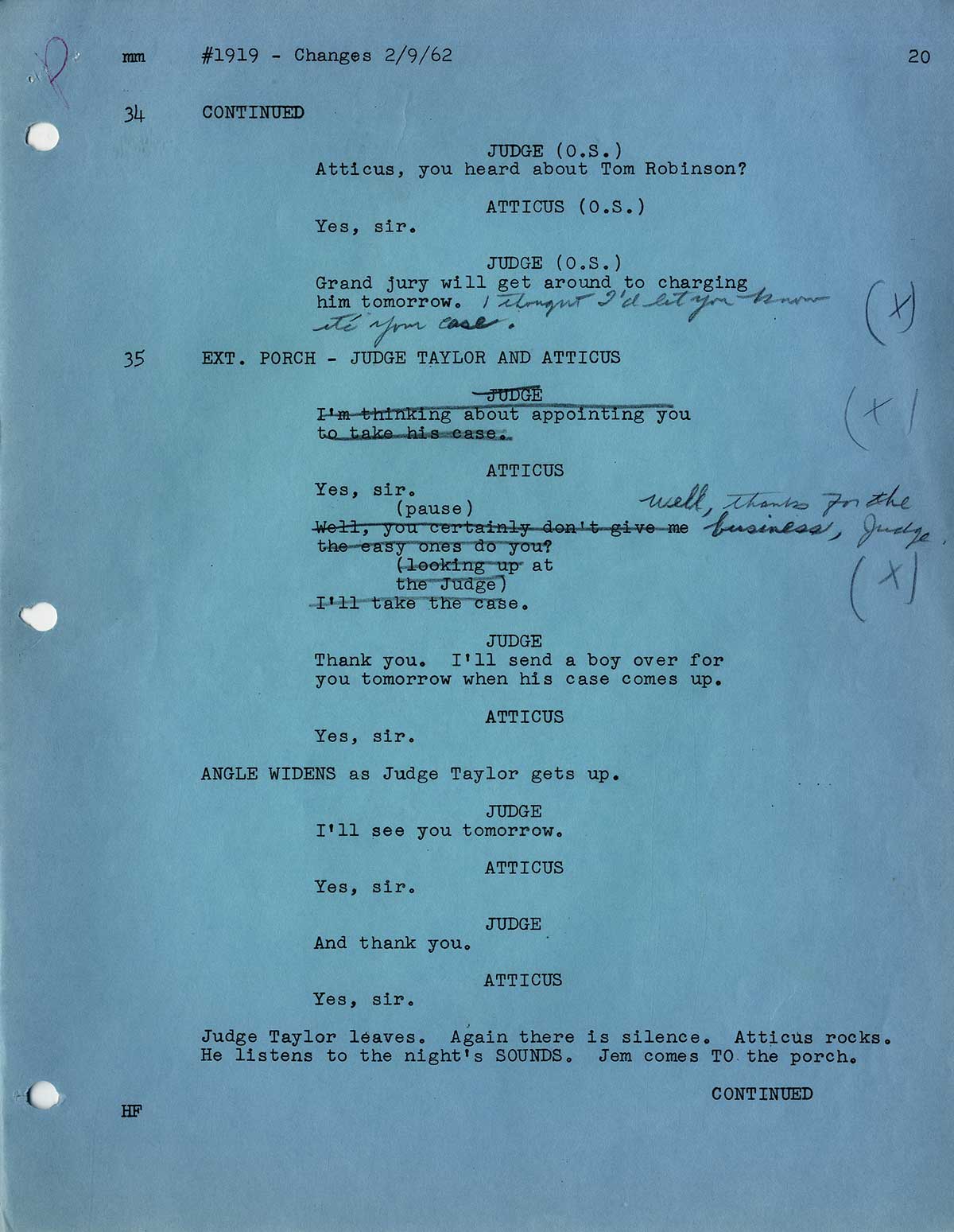

- Final Screenplay [the title page reads “First Draft,” a typo corrected in pencil to read “Final Draft”] by Horton Foote. December 27, 1961. Printed wrappers, brad bound, quarto, mimeograph, 157 pp. One page has a tear repaired with tape. Many pages have markings in pencil. A few have MS revisions to the script. This script contains various typed & dated revisions on yellow onionskin paper, dated from 12/11/61 to 2/6/62.

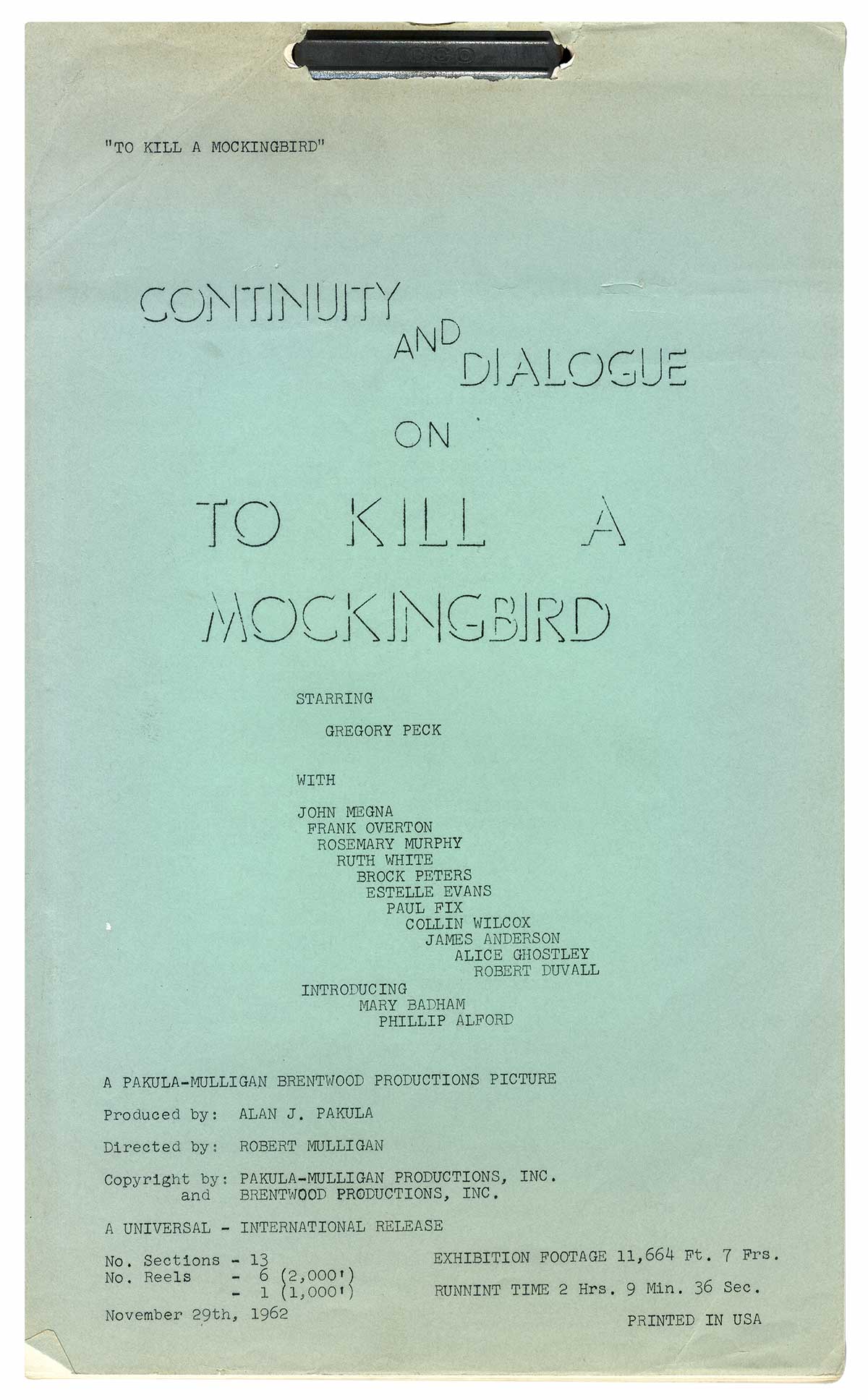

- Continuity and Dialogue, November 29, 1962. Small folio, clasp bound at top, mimeograph, 109 pp. Printed wrappers, a few pages at end have small marginal tears and creasing, front wrapper detached from clasp, overall NEAR FINE in VERY GOOD+ wrappers.

An archive comprising a very early draft, a final one, and a definitive post-production script which enumerates every shot in the film and every line of dialogue.

The first two scripts are the first and final drafts of the Academy Award-winning screenplay by Horton Foote, adapted from the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Harper Lee, an autobiographical story of a white girl with an attorney father growing up in the 1930s in the segregated South.

Nelle Harper Lee was born on April 28, 1926, in Monroeville, Alabama, and died there on February 19, 2016. For years, TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD was her only published fiction until 2015, when GO SET A WATCHMAN, an alternate draft version of MOCKINGBIRD written in the 1950s, was published as a sequel.

Horton Foote (1916-2009) was another Southern writer, born in Wharton, Texas, and honored in his own right for teleplays like THE TRIP TO BOUNTIFUL (1953 – later, a 1985 movie), original screenplays such as TENDER MERCIES (Bruce Beresford, 1983) for which Foote received an Academy Award, and plays like THE YOUNG MAN FROM ATLANTA for which he received the 1995 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. His nine-play biographical series, THE ORPHANS’ HOME CYCLE (ROOTS IN A PARCHED GROUND, CONVICTS, LILY DALE, THE WIDOW CLAIRE, COURTSHIP, VALENTINE’S DAY, 1918, COUSINS, and THE DEATH OF PAPA) ran in repertory Off-Broadway from 2009 to 2010.

TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD was the second film made by the team of producer Alan J. Pakula (1928-1998) and director Robert Mulligan (1925-2008), who specialized in sensitive films featuring young people as protagonists. Their first film together, FEAR STRIKES OUT (1957) starred Anthony Perkins as a young baseball player battling neurosis. After their much-acclaimed film version of TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD, the team made LOVE WITH THE PROPER STRANGER (1963) starring Steve McQueen and Natalie Wood as young lovers, INSIDE DAISY CLOVER (1965) with Natalie Wood as a teenaged movie star, and UP THE DOWN STAIRCASE (1967) about a young teacher, played by Sandy Dennis, and her inner city students in a New York high school. Without Pakula, Mulligan directed the very successful SUMMER OF ’42 (1971), a coming-of-age story set on Nantucket Island during the war. Pakula later became a director himself, with several major films to his credit, including KLUTE (1971), THE PARALLAX VIEW (1974), ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN (1976), and SOPHIE’S CHOICE (1982).

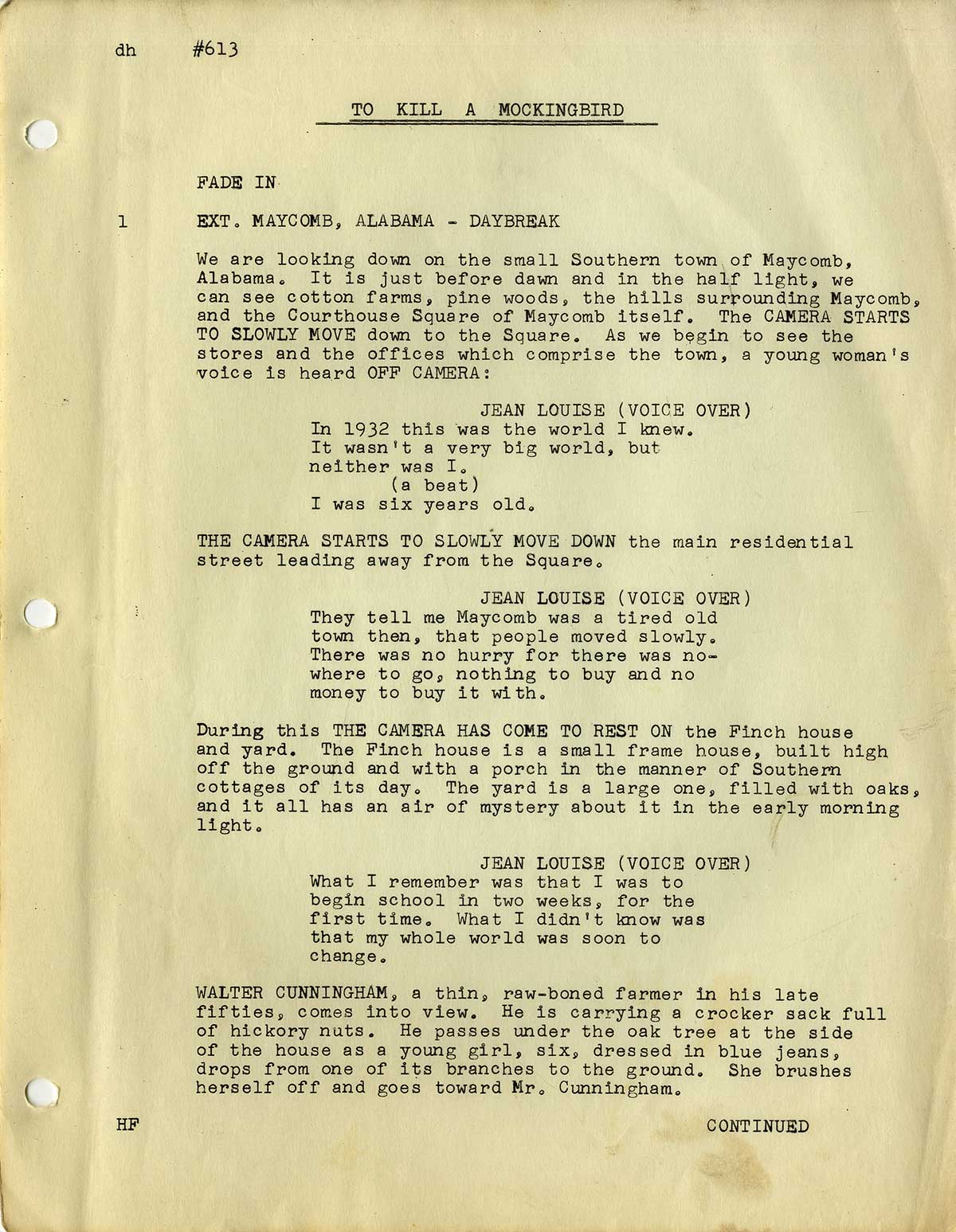

Foote’s first draft screenplay of MOCKINGBIRD begins with an exterior shot – “We are looking down on the small Southern town of Maycomb, Alabama” – and the voiceover of its protagonist, Jean Louise aka “Scout,” as an older woman, looking back:

“JEAN LOUISE (VOICE OVER)

In 1932 this was the world I knew. It wasn’t a very big world, but neither was I.

(a beat)

I was six years old.“

The opening voiceover of the completed movie, spoken by an uncredited Kim Stanley, is more literary and elaborate, closer to author Harper Lee’s original text: “Maycomb was a tired old town in 1932 when I first knew it. Somehow it was hotter then . . . .“

The first and final drafts of Foote’s screenplay, notwithstanding some tweaks and revisions, are not substantially different from each other, and the final draft screenplay is not significantly different from the completed film – though the film deletes some sequences for the sake of length. The final draft is essentially a more polished version of the first draft, and includes more indications of camera angles, e.g., in an early scene:

“The ANGLE WIDENS as Atticus starts for the front yard to get the morning paper, Scout after him.“

Gregory Peck received an Academy Award for playing the role of Atticus Finch, a character based on author Lee’s attorney father.

The role of friendly neighbor, Miss Maudie Atkinson, is gradually diminished from first draft to final draft to the completed film. In the drafts, it is Maudie who first talks about the negro Tom Robinson who allegedly raped and beat the white girl, Mayella Ewell. In the movie, we don’t hear about Tom Robinson until the town judge shows up on Atticus’s porch one night asking him to take Tom’s case, essentially marking the beginning of the film’s second act. (In the final draft, the dialogue scene between Atticus and Miss Maudie concerning Tom Robinson has been crossed out with a pencil. The final draft screenplay has numerous duplicate yellow pages marked with pencil to reflect such revisions).

In the transition from book to first draft screenplay to final draft screenplay to completed movie, we see an increasingly sharper definition of dramatic structure. The First Act introduces young Scout, her brother Jem, their father Atticus, their friend Dill, and their mysterious unseen neighbor, Boo Radley. The Second and most lengthy Act is all about the trial, conviction, and ultimate fate of Tom Robinson as perceived by the children. The Third Act, almost an epilogue, taking place on Halloween some months after the trial, is about an attack on Atticus’s children by the alleged rape victim’s father, Bob Ewell, and how they are rescued by the hitherto-unseen Boo. Discussing his screenplay, screenwriter Foote talked about his efforts to compress the major events of the novel into the space of slightly more than one year. The two screenplays have notably more scenes of exposition and backstory, in the form of characters engaging in gossip about each other, than are included in the completed film.

Among the deletions – Scout’s first day in school in Miss Caroline’s class is depicted at length in the two screenplays (as it is in the book). In the movie, we don’t see it, but only hear about it after Scout gets into a fight with one of the boys in her class after school.

One thematic element that gains increasing importance in the evolution from first draft to final draft to completed film is the gun motif. Largely absent from Foote’s initial draft, it first appears on page 6 of the final draft, when older brother Jem complains about his father to neighbor, Miss Maudie:

“JEM

He won’t let me have a gun. He’ll only play touch football with me… never tackle.

In both drafts, Jem invites the poor boy, Walter Cunningham, to dinner following his after-school fight with Scout, but only in the final draft does the issue of guns arise when Jem learns that the little farmer’s boy, unlike Jem, has his own gun. This leads to one of the most famous exchanges in the movie when Atticus talks about the time his father gave him a gun:

ATTICUS

He told me: “Never point at anything in the house,” and that he’d rather I just shoot tin cans in the back yard. But he said, sooner or later, he supposed, the temptation to go after birds would be too much and to shoot all the blue jays I wanted if I could hit them; but to remember, it was a sin to kill a mockingbird.

JEM

Why?

ATTICUS

Well, I reckon because mockingbirds don’t do anything but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat people’s gardens, they don’t nest in corn cribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us ….“

In the screenplay’s first draft, this speech comes much later.

The gun motif culminates in the disturbing scene where the sheriff enlists the peace-loving Atticus to shoot a rabid dog. Only then does Jem learn that his father is, in fact, the best shot in the county. (The screenplay’s set-up to the dog shooting scene, involving the children and their housekeeper, Calpurnia, is deleted from the completed film. Also cut is a lengthy sequence following the dog-shooting scene where the elderly Mrs. Dubose says that Atticus should be shot like “that dog” for defending a negro, and angry Jem destroys her prized camellia bushes. Atticus, hearing of the incident, makes Jem atone for it by reading to her regularly.)

At the close of the narrative, when the children are rescued from the racist Bob Ewell by their mysterious recluse protector, Boo Radley (Robert Duvall in his film debut), it is little Scout who recalls what Atticus said about mockingbirds, explaining why it would be wrong to reveal Boo’s role in Ewell’s death:

“SCOUT

Well, it’d be sort of like shootin’ a mockingbird, wouldn’t it?“

TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD is many things simultaneously – it’s a memoir of growing up in the Depression-era South; it’s a Civil Rights story that turns into a courtroom drama; and the treatment of the Boo Radley character adds to the whole story a level of fairy tale and myth. Screenwriter Horton Foote’s major achievement is to give dramatic shape to the characters and events of Harper Lee’s classic novel while retaining the book’s language, texture, and feeling.

Out of stock

Related products

-

ASPHALT JUNGLE, THE (1950) Half sheet poster

$700.00 Add to cart -

![[Doyle, Arthur Conan (source work)]: "SHERLOCK HOLMES FIGHTS BACK" [released as: SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SECRET WEAPON] 22 May - 17 June 1942](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/SherlockHolmesFightsBack-Script1-540x724.jpg)

SHERLOCK HOLMES FIGHTS BACK [released as SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SECRET WEAPON] (May 22-Jun 17, 1942) Screenplay

$2,000.00 Add to cart -

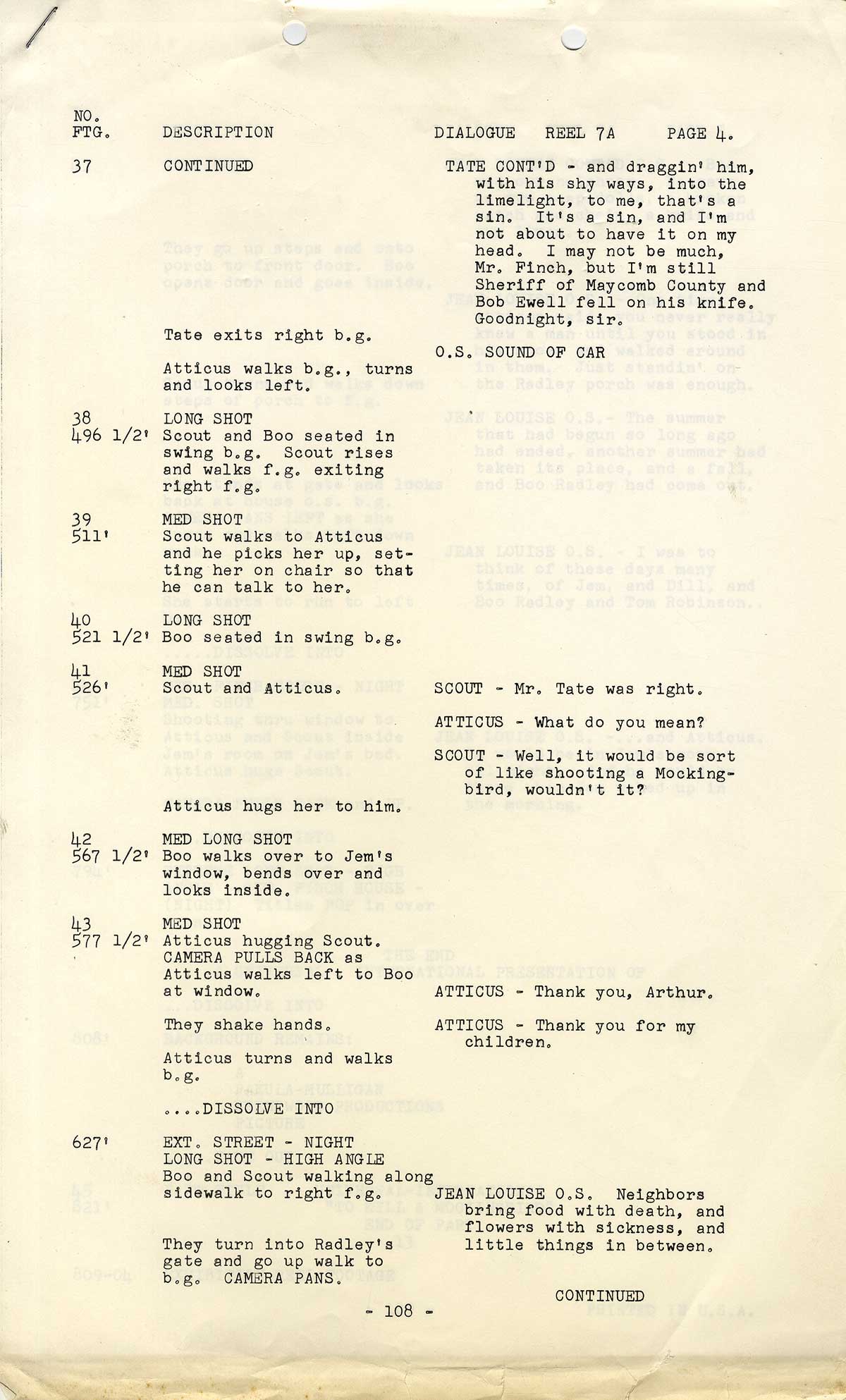

DIVINE IN AFRIKA (ca. 1983) Event poster

$650.00 Add to cart -

WINGS OF EAGLES, THE (1957) Two variant film scripts

$2,650.00 Add to cart