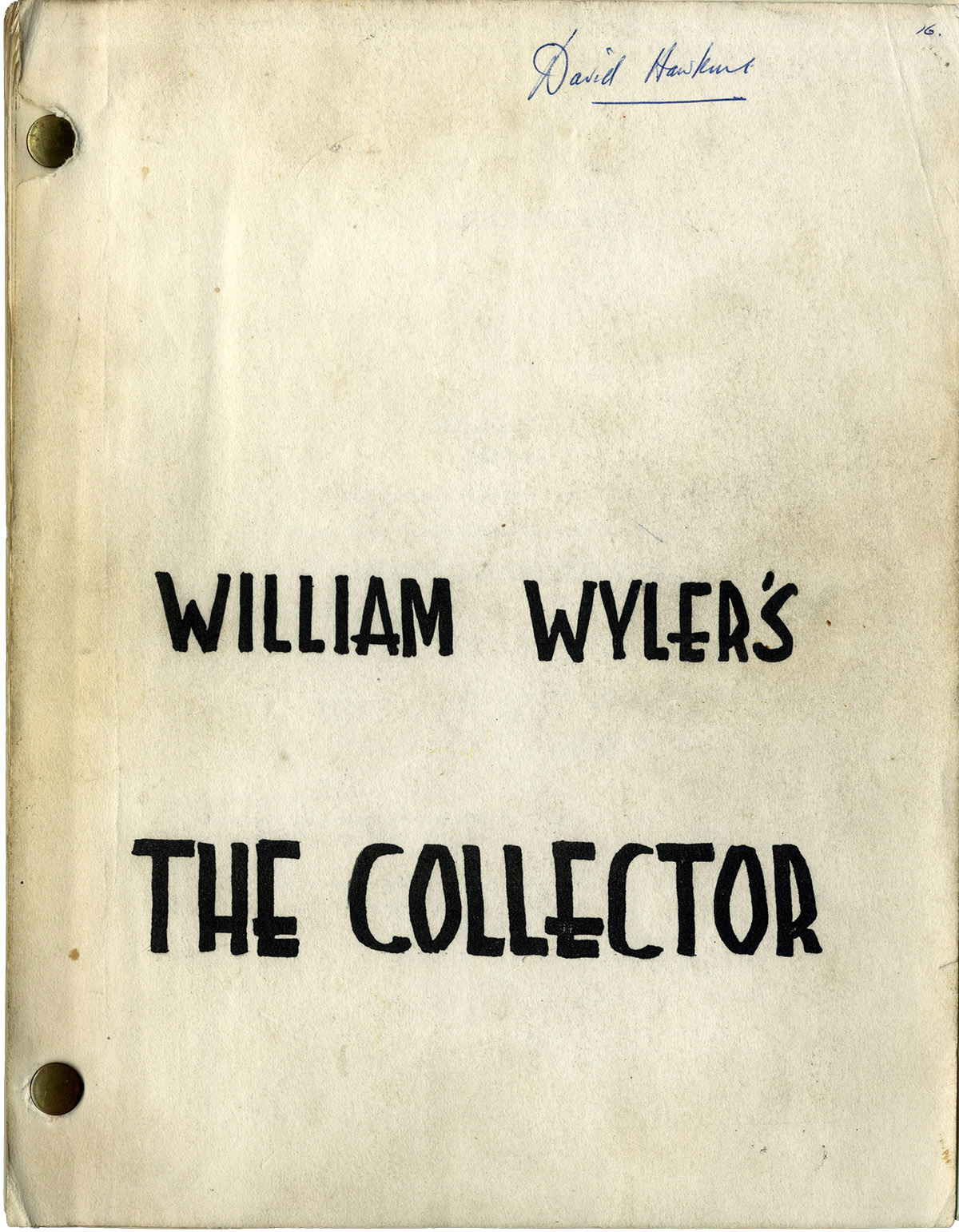

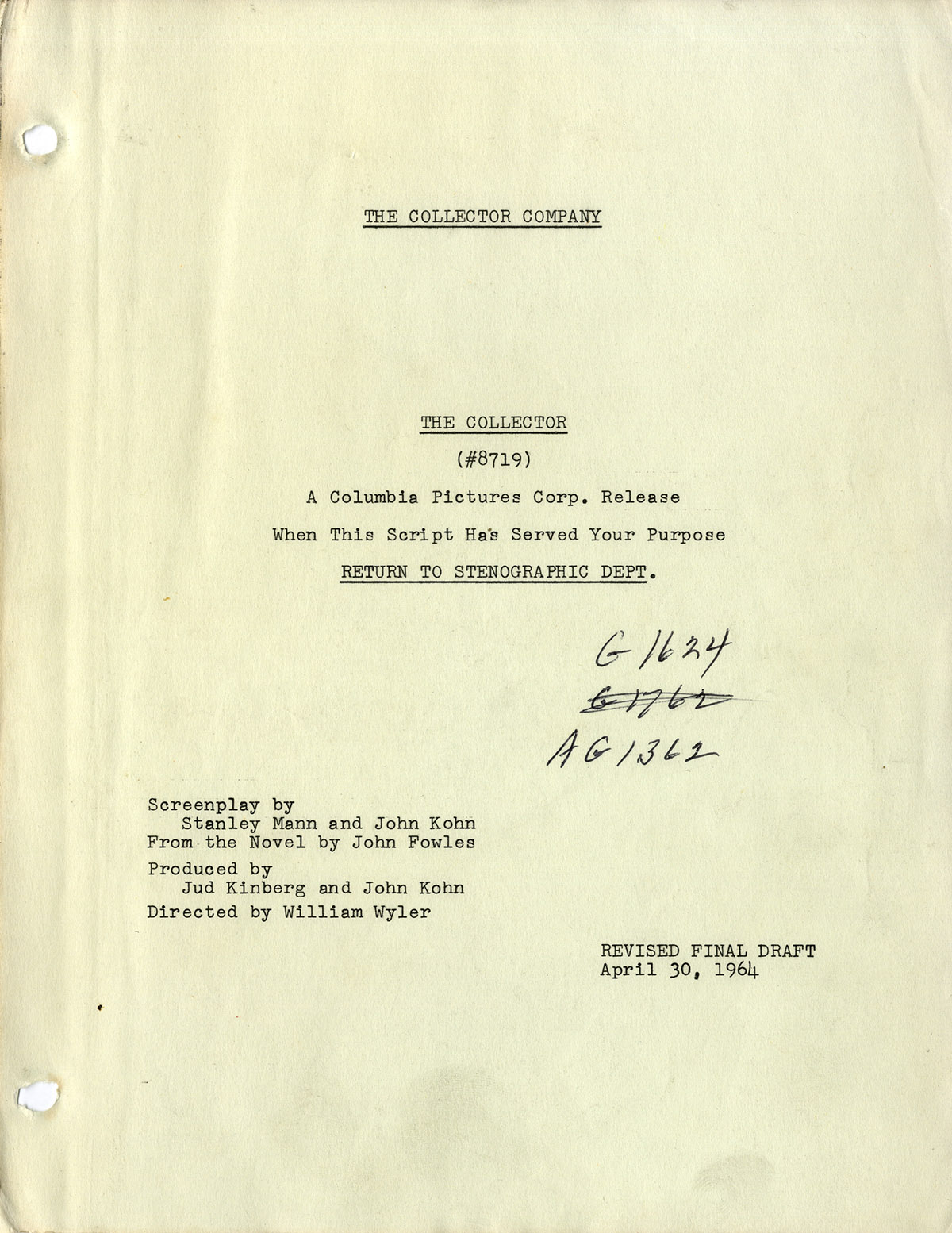

COLLECTOR, THE (Apr 30, 1964) Revised Final Draft screenplay by Stanley Mann & John Kohn

John Fowles (source), William Wyler (director) Vintage original film script, USA. Mimeograph, quarto, brad bound, 144 pp., printed wrappers, front wrapper detached from top brad, staining to back cover, JUST ABOUT FINE in VERY GOOD- wrappers, final page of revision dated 5-20-64.

THE COLLECTOR was the first published novel of English author, John Fowles (1926-2005), and was an immediate best-seller. Following THE COLLECTOR’s success, Fowles’s work became increasingly post-modern and metafictional, including such novels as THE MAGUS, THE FRENCH LIEUTENANT’S WOMEN, and A MAGGOT.

THE COLLECTOR itself approaches the metafictional insofar as its second part consists of fragments of the diary of the captured (“collected”) woman, an art student named Miranda, and the third part is narrated by her captor, Freddie, including his reactions to what he reads in her diary.

Fowles’s novel was optioned by American producer John Kohn (1925-2002), the first of several prestigious film productions by Kohn, who also co-authored this screenplay adaptation with Stanley Mann (1928-2016), a prolific Canadian-born screenwriter who worked on THE MOUSE THAT ROARED, THE MARK, WOMAN OF STRAW, A HIGH WIND IN JAMAICA, THE NAKED RUNNER, METEOR, and EYE OF THE NEEDLE, among many others. Kohn and Mann’s screenplay for THE COLLECTOR was nominated for an Academy Award. Kohn eventually became head of production for EMI.

To direct THE COLLECTOR, Kohn and co-producer Jud Kinberg hired the Alsatian-born William Wyler (1902-1981), one of the best known and most honored of “Hollywood professionals” who had helmed such Best Picture Academy Award-winners as MRS. MINIVER (1942), THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES (1946), and BEN-HUR (1959).

For Wyler, THE COLLECTOR was an opportunity to exercise Hollywood’s increasing freedom with regard to sexual and other controversial subject matters, something he had already done in his previous film, THE CHILDREN’S HOUR (1961). Today, THE COLLECTOR is remembered primarily for the remarkable performances of its two young leads, Terence Stamp as Freddie and Samantha Eggar as Miranda, both of whom won best acting awards at the 1965 Cannes Film Festival.

This screenplay appears to be the final shooting script, except that it includes roughly 35 minutes of material that was shot, but cut from the completed film. Much of that material concerns Miranda’s relationship with an older artist named George Paston, played in the deleted footage by Kenneth More. According to director Wyler, “Some of the finest footage I ever shot wound up on the cutting room floor.”

However, it is more likely that the removal of the Kenneth More footage significantly improved the film. The relationship of a young artist with an older mentor who says, as he critiques her drawings, “You know, if you were ugly, I wouldn’t be wasting my time telling you all this”, is comparatively banal in contrast to Miranda’s relationship with Freddie, the working-class youth who abducts her and holds her prisoner in the absurd hope that she might fall in love with him after she gets to know him. Cutting Miranda’s relationship with the older artist results in a tighter film that becomes essentially a two-character drama.

Including the Kenneth More/artist scenes and other deleted sequences would have resulted in a movie that was over 2 and 1/2 hours long, instead of the tightly executed suspense melodrama that we ultimately got.

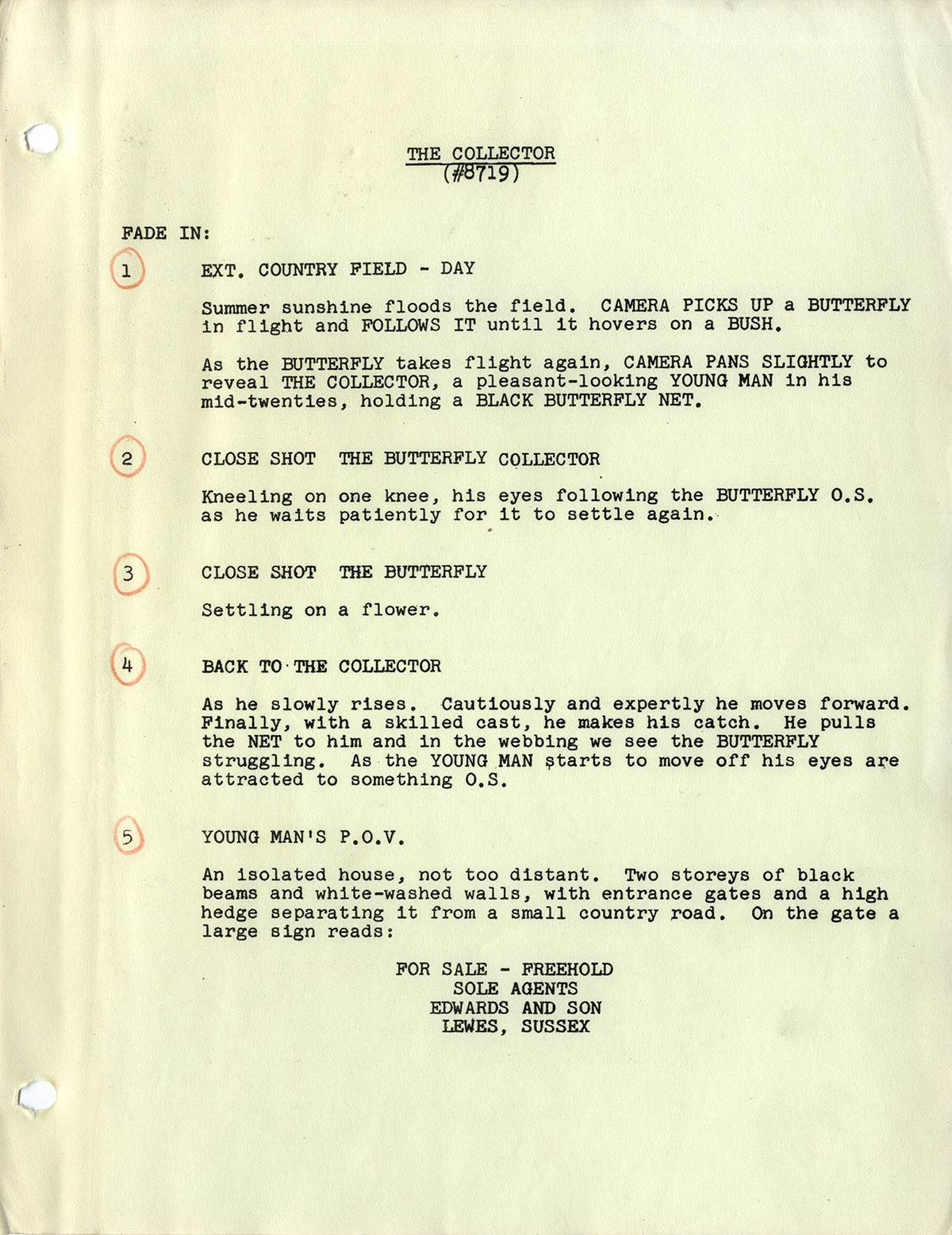

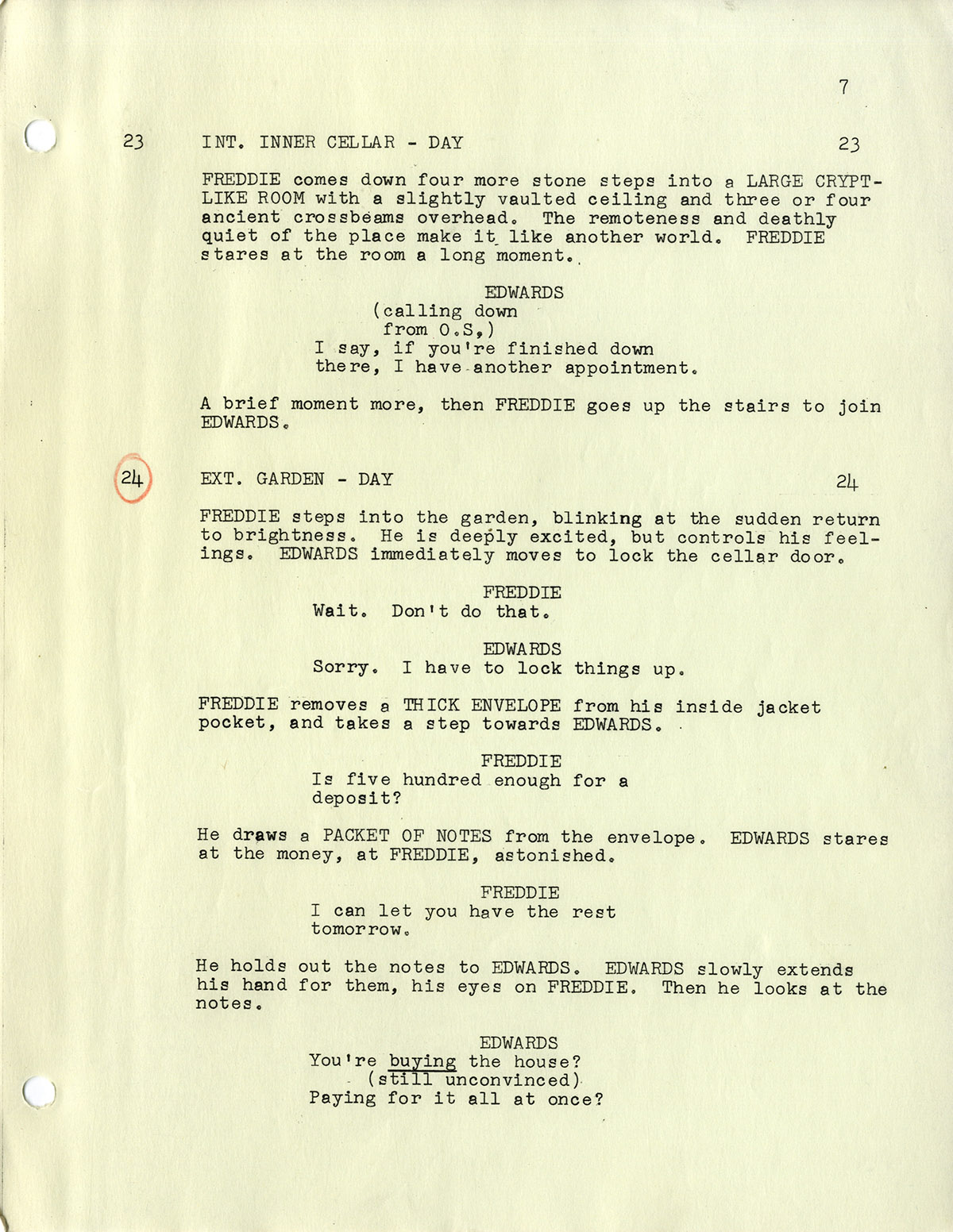

While the story’s overt subject is Freddie’s romantic longing for the beautiful Miranda (he “respects” her too much to initiate sex with her, and when it is she who attempts to initiate sex, he loses that respect), the book and movie’s real subject is class envy. As a working class bank clerk, Freddie feels like he could never approach the affluent middle-class-educated Miranda in “real life”, which is why – when he is lucky enough to win a large sum of money in a football pool – he concocts his elaborate scheme to rent a house in the middle of nowhere, build a comfortable prison in the basement, and abduct her there.

FREDDIE

(as he binds her)You always make me feel like I’m being cruel.

Well, I can tell you there’d be a blooming lot

more of this if more people had the money and

the time. Anyway, there’s more of it now than

anyone knows. The police keep it dark.

Freddie’s hobby is entomology – the collecting and mounting of butterflies – and the screenplay frequently compares his kidnapping of Miranda to his butterfly collecting. In one brief scene that is cut from the completed film, Freddie attempts to purchase some chloroform from a pharmacist, who is reluctant to sell it to him until Freddie shows him a “breeding cage” with a live butterfly inside, proof of his hobby. For anyone who saw PSYCHO five years earlier, Freddie’s butterfly collecting is reminiscent of Norman Bates’s favorite pastime: stuffing birds. Similarly, the way Freddie holds Miranda prisoner may remind the reader or viewer of the way Bette Davis holds Joan Crawford prisoner in 1963’s WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE? All three of these films – Hitchcock’s PSYCHO, Aldrich’s WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE?, and Wyler’s THE COLLECTOR – are examples of filmmakers from previous, more censored, generations taking advantage of the 1960s new freedoms.

Aside from the deleted sequences, the most significant difference between this screenplay and the completed film is how it ends. In both versions Miranda dies, but in the version that was filmed her death is more ironic, more the result of her own actions.

Released in a pivotal year, 1965, the same year as Arthur Penn’s MICKEY ONE, John Schlesinger’s DARLING, Richard Lester’s HELP! and THE KNACK, Roman Polanski’s REPULSION and Tony Richardson’s THE LOVED ONE, it would be a mistake not to include Wyler’s THE COLLECTOR among the outstanding films of the burgeoning British and American New Waves.

Out of stock

Related products

-

SLEEP ON THE ROOF (1967) Unproduced script based on the life of Margaret Sanger

$500.00 Add to cart -

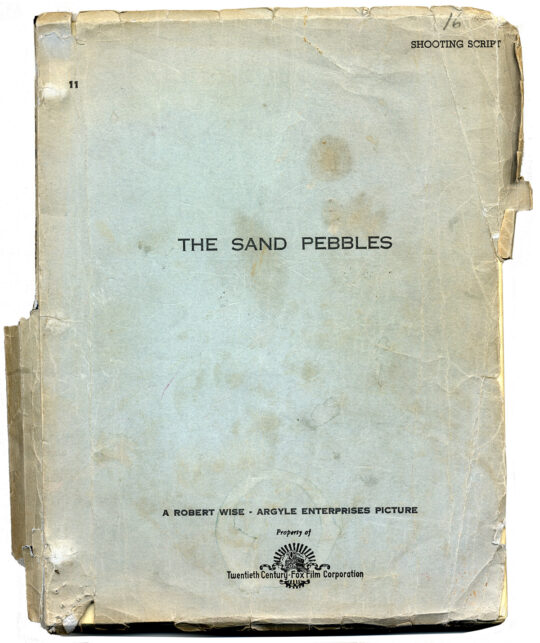

SAND PEBBLES, THE (Nov 1, 1965) Shooting script by Robert Anderson

$1,150.00 Add to cart -

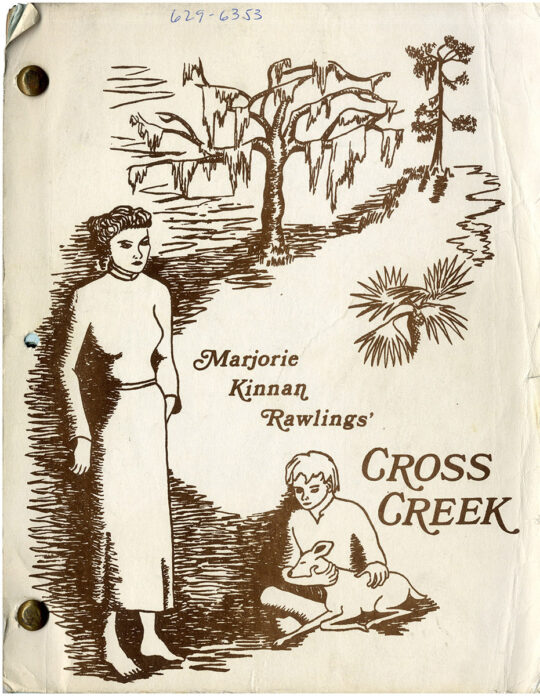

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart -

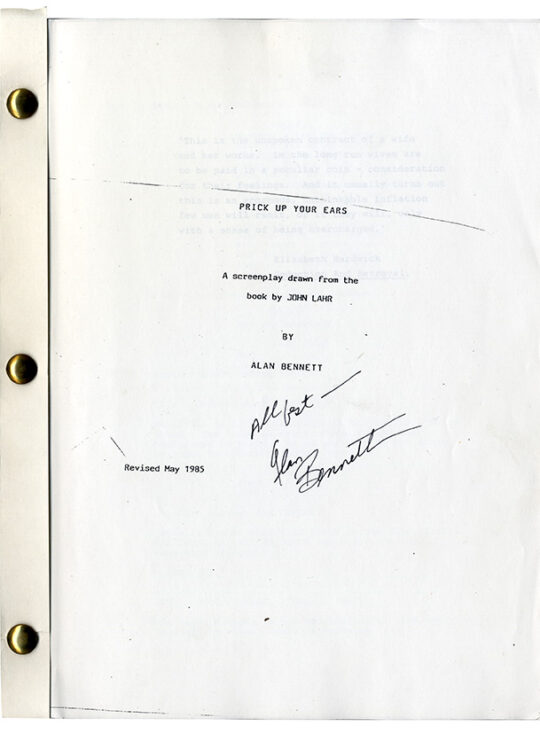

PRICK UP YOUR EARS (May 1985) Revised film script

$650.00 Add to cart