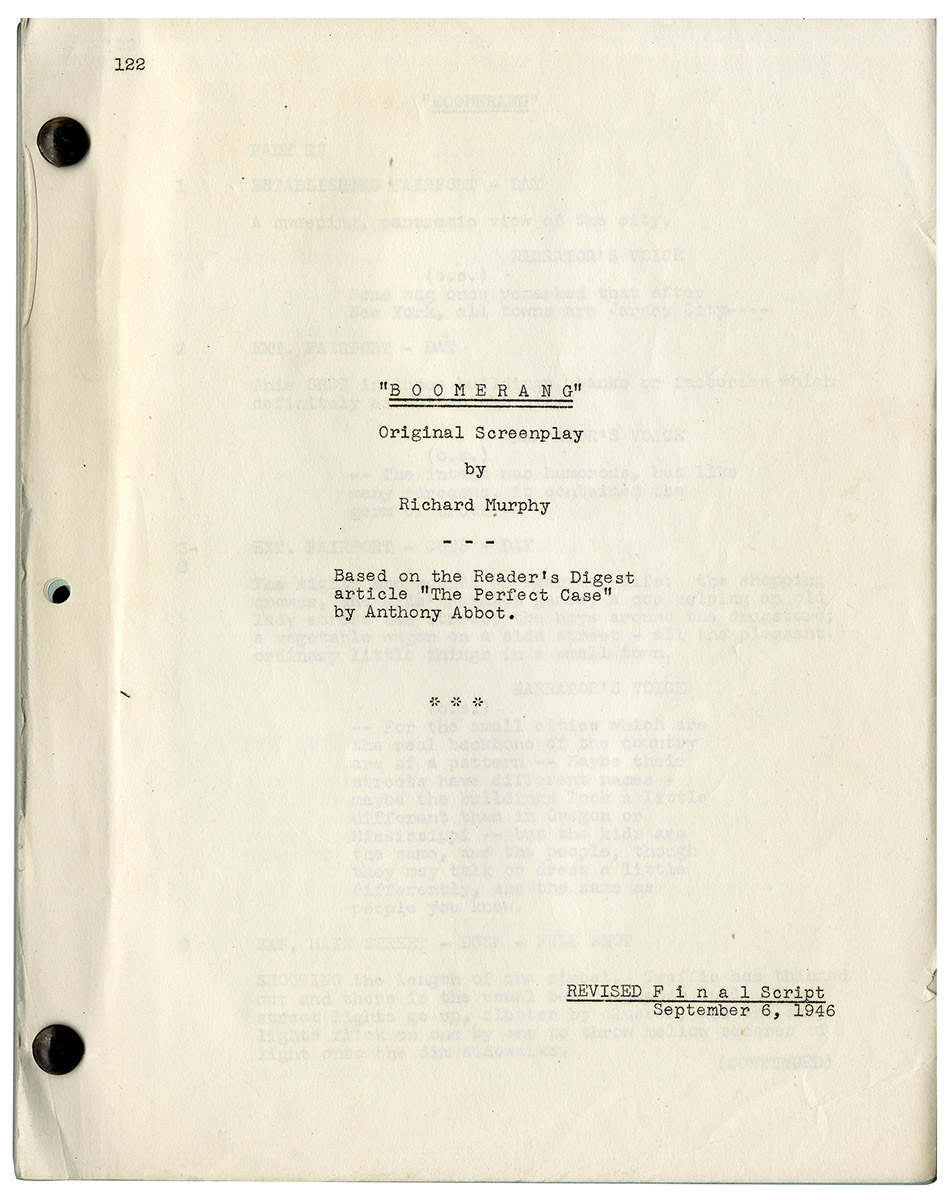

(Film noir) BOOMERANG (1946) Revised film script by Richard Murphy

Los Angeles: Twentieth Century Fox, 1946. Vintage original film screenplay, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.), 162 leaves, with the last leaf of text numbered 155. Mimeograph, with blue revision pages throughout, dated variously between 9/18/46 and 9/25/46. Final leaf with one marginal tear (mended with archival paper), near fine overall, brad bound.

Boomerang (1947) was the third feature directed by world-class auteur Elia Kazan, and his first in the mode we now call film noir. More accurately, the film is a hybrid of post-war neo-realism and noir. Shot almost entirely on location in Stamford, Connecticut, close to where the story’s actual events took place, Boomerang has the naturalistic look of other true crime docudramas like 13 Rue Madeleine and The Naked City, but the film’s subject matter — an ordinary man wrongfully accused of murder and the corruption bubbling underneath the surface of an apparently placid small town — is pure 1940s noir.

The producer of Boomerang, Louis de Rochemont, was known for his March of Time series of documentary shorts. Boomerang‘s screenwriter, Richard Murphy, also authored the screenplays for such notable noirs as Cry of the City (Robert Siodmak, 1948), Panic in the Streets (Kazan, 1950) and Compulsion (Richard Fleischer, 1959). His Boomerang screenplay was nominated for an Academy Award.

Boomerang‘s fascinating split between neo-realism and noir is apparent even in the screenplay and film’s opening sequence. The establishing shots of the town where the events are supposed to have taken place realistically show “the sights and sounds of everyday life” including various pedestrians and the kindly minister of the town’s Episcopal church. Abruptly, we cut to a close-up of the minister in profile and a gun enters the frame, pointed at the back of the minister’s head, a shockingly noir image that is punctuated by reaction shots of the bystanders as we hear the gunshot fired.

Murphy’s September 6, 1946 “Final” screenplay is close to what was actually filmed, but it is far from identical. Clearly, prior to the shooting someone with a strong sense of narrative structure — most likely 20th Century Fox studio head, Darryl F. Zanuck — revised the screenplay and reorganized its structure, deleting some sequences and polishing others.

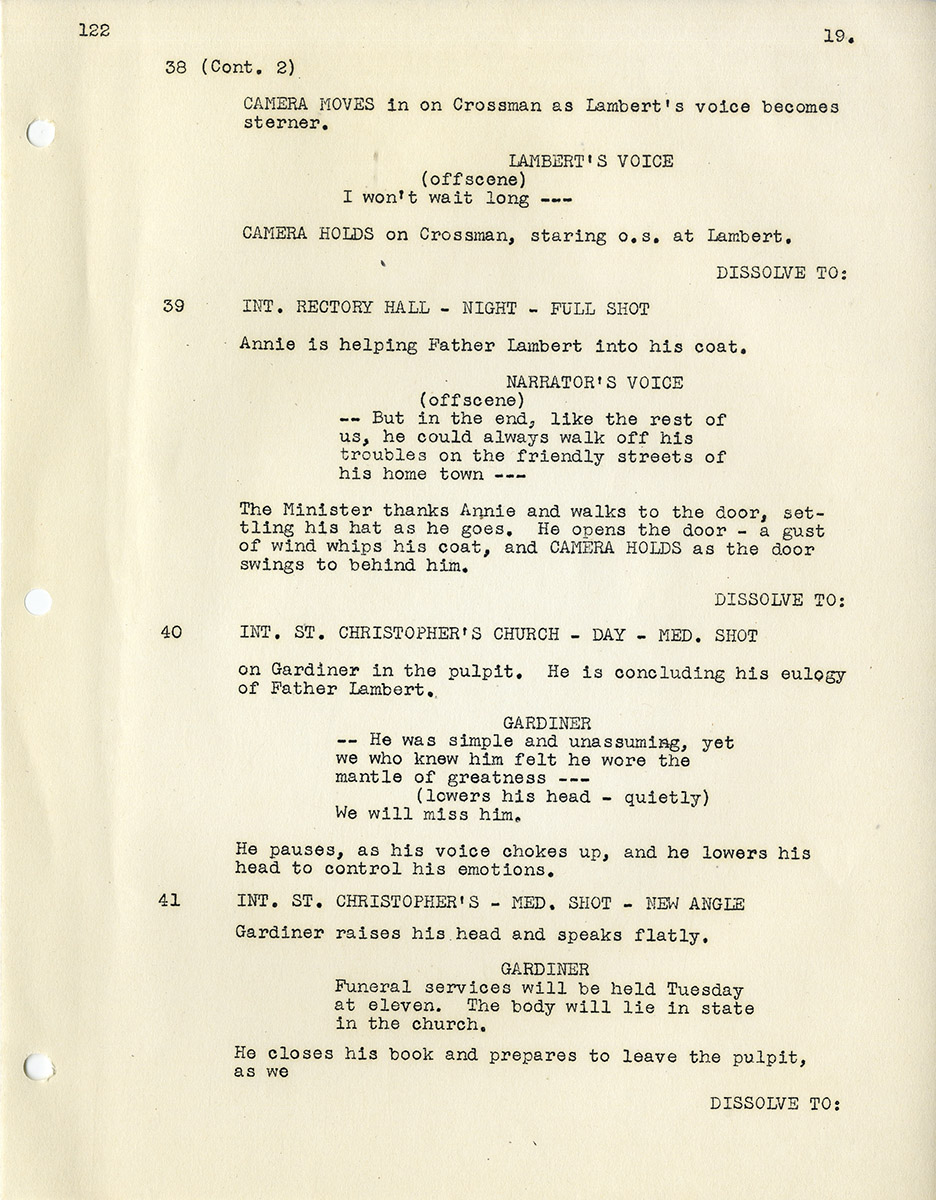

For example, in Murphy’s screenplay, immediately following the shooting of the minister there is a 7-page dialogue sequence taking place in the minister’s study in which we are introduced to a half-dozen characters, including someone whom we will later learn is the real murderer. That sequence is entirely eliminated from the movie which instead cuts directly to the minister’s funeral.

The film’s first act is all about politics. The town’s Reform party, which is presently in power, pressures the police to find the murderer as soon as possible in order to preserve its prestige. The party that is out of power, including the well-to-do publisher of the local newspaper, wants to do everything it can to make the Reform party look bad. Working for the newspaper is a seasoned reporter named Woods (Sam Levene) who is simply interested in the truth. In the movie, but not in the screenplay, he is given a sidekick, a cub reporter who functions as kind of a sounding board.

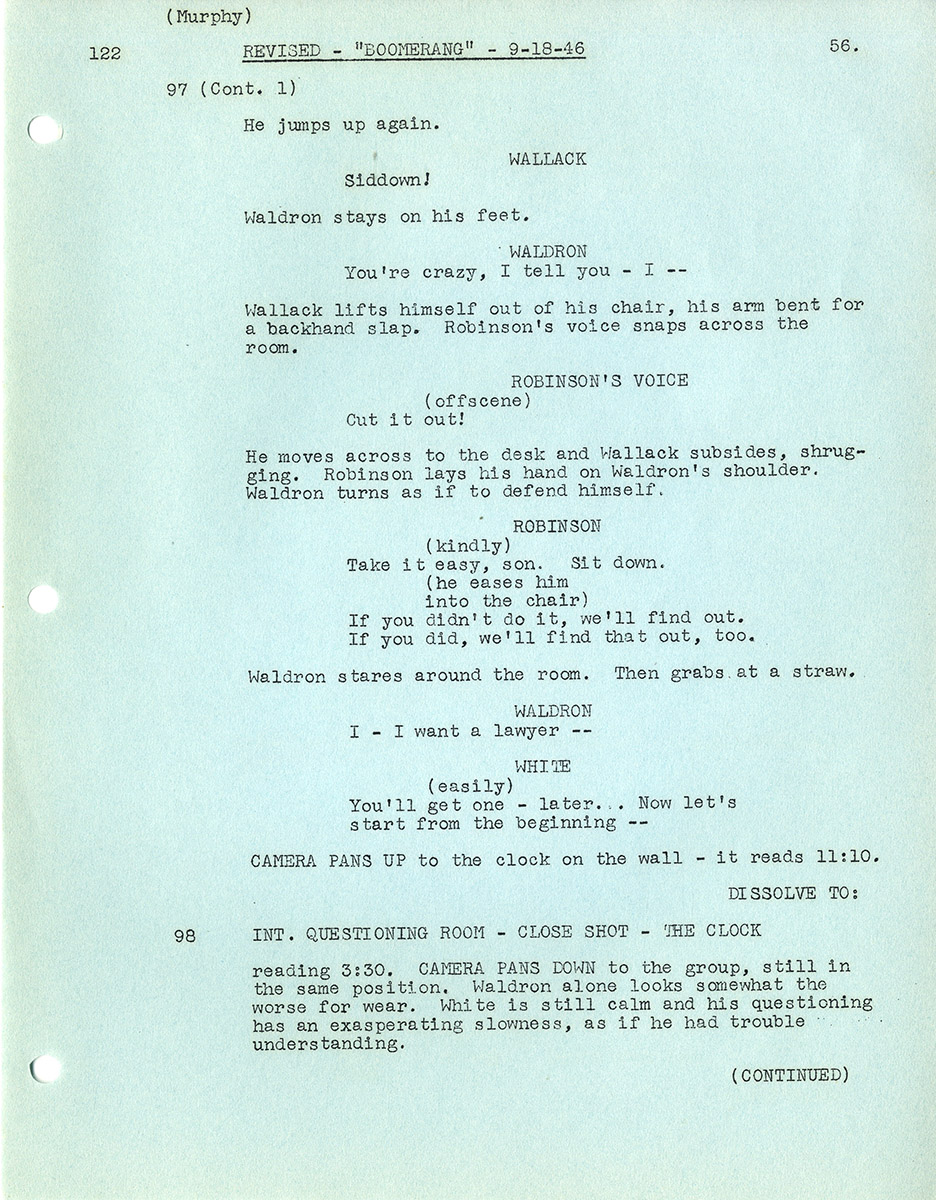

The second act, focusing mainly on the police, is all about the capture and interrogation of the most likely suspect, a young World War II veteran named Waldron (Arthur Kennedy). All of the evidence, including the testimony of the eyewitnesses and a gun found on the suspect with apparently matching bullets, seems to point to the suspect’s guilt. There is a brutal interrogation in which the suspect is kept awake for what seems like days, resulting in a signed confession. We get to know the story’s real protagonist, state’s attorney Henry Harvey (Dana Andrews) who at first believes the suspect is guilty, but after interviewing him begins to suspect that something is amiss.

The third act, where screenwriter Murphy really shows his skill, is a lengthy courtroom sequence in which state’s attorney Harvey systematically dismantles all of the evidence pointing to Waldron’s guilt and sets him free. In the movie, as opposed to the screenplay, there is a bit of a cheat. In the screenplay, there are scenes of state’s attorney Harvey and his assistants reenacting the crime that precede the courtroom scene. In the movie, we don’t see or learn about any of the evidence that exonerates Waldron until Harvey presents it in court — a plainly more dramatic way to introduce the material.

The screenplay and film have a rather odd flashback scene where we see the minister privately counseling the man who will eventually murder him (the real murderer is played by creepy-looking Philip Coolidge, an actor best known for playing the homicidal repertory cinema owner in William Castle’s The Tingler). The minister, providing a motive for his own death, threatens to turn the parishioner in for his “strange repressions and vices”, but curiously we never learn what his problem actually is. His suggested vice might be something as innocuous as having sex with another man, an act that would not cause a fuss today but would have been anathema in the 1940s.

At Boomerang‘s conclusion, the omniscient narrator tells us that the real murderer died in a freak car accident and that the heroic state’s attorney (based on real-life attorney Homer Cummings) went on to become president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s attorney general. The social order has been reestablished.

Pagination (all revision pages blue unless otherwise noted): [title], [1], 2, 3 (9/25/46), 4-5 (9/18/46), 6, 7-10 (9/18/46), 11, 12-13 (9/18/46), 13A (9/18/46), 14,15 (9/18/46), 16-19, 20-21 (9/18/46), 21A (9/18/46), 22, 23-26 (9-18-46), 26A (9-18-46), 27(9/18/46), 28, 29 (9/18/46), 29A (9/18/46), 30-33 (9/18/46), 34, 35-36 (9/18/46), 37, 38-40 (9/18/46), 41, 42 (9/18/46), 42A (9/18/46), 43, 44-47 (9/18/46), 47A (9/18/46), 48, 49 (9/18/46),50, 51 (9/18/46), 52, 53-54 (9/18/46), 55, 56-57 (9-18-46), 58 (9/18/46), 58A (9/18/46), 59, 60-61 (9/18/46), 61A (9/18/46), 62 (9/18/46), 62A (9/18/46), 63-64, 65-66 (9/18/46), 66A (9/18/46),67, 68 (9/18/46), 69, 70 (9/18/46), 71-74, 75 (9/23/46), 76, 77-79 (9/18/46), 80-82 (9/23/46), 82A (9/23/46), 82B (9/23/46), 83-86, 87 (9/23/46), 87A (9/23/46), 88-90 (9/23/46), 91-94, 9596 (9/23/46), 97 (9/25/46), 98-99 (9/23/46), 100-104, 105 (9/23/46), 105A (9/23/46), 106-107 (9/23/46), 108 (9/24/46), 108A (9/24/46), 108-B (9/24/46), 109-112, 113-114 (9/24/46), 115-116,117 (9/24/46). 118-119, 120 (9/24/46), 120A (9/23/46), 121-122, 123 (9/24/46), 124-128, 129(9/24/46), 130, 131-134 (9/25/46), 135-144, 145 (9/24/46), 146-147, 148 (9/24/46), 149, 150-151 (9/25/46), 152 (9/25/46, notation), 153-155.

In stock

Related products

-

RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT, A (1987) Larry Cohen-signed script

$625.00 Add to cart -

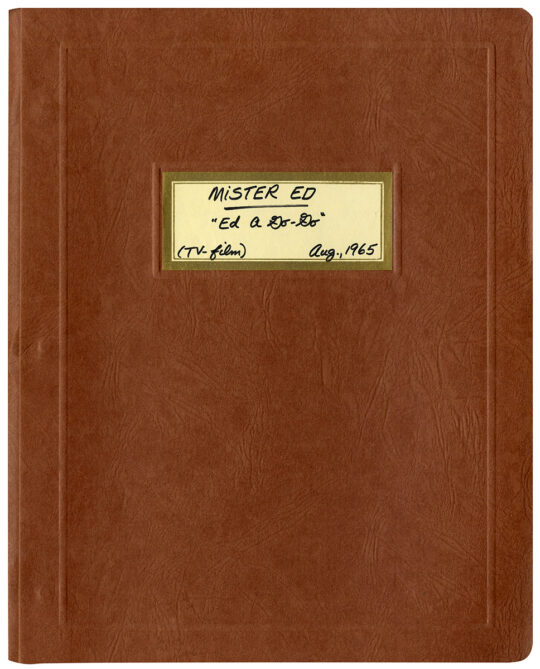

MISTER ED – “ED A GO-GO” (1965) TV script signed by Johnny Crawford

$325.00 Add to cart -

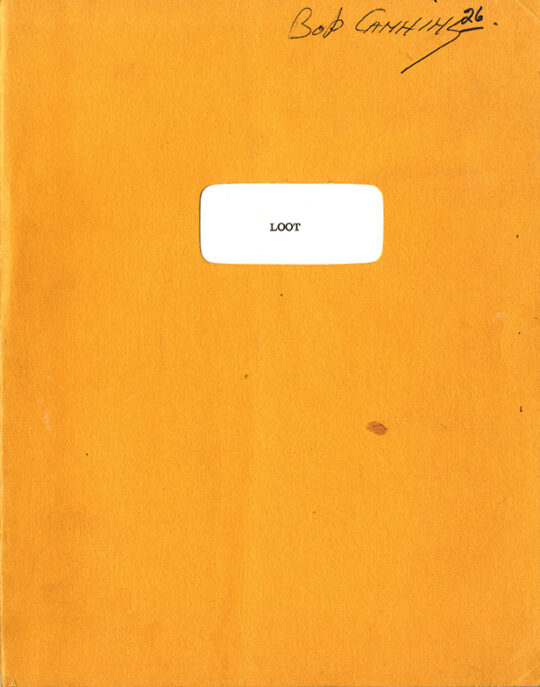

LOOT (ca. Sep 1969) Final Draft screenplay

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

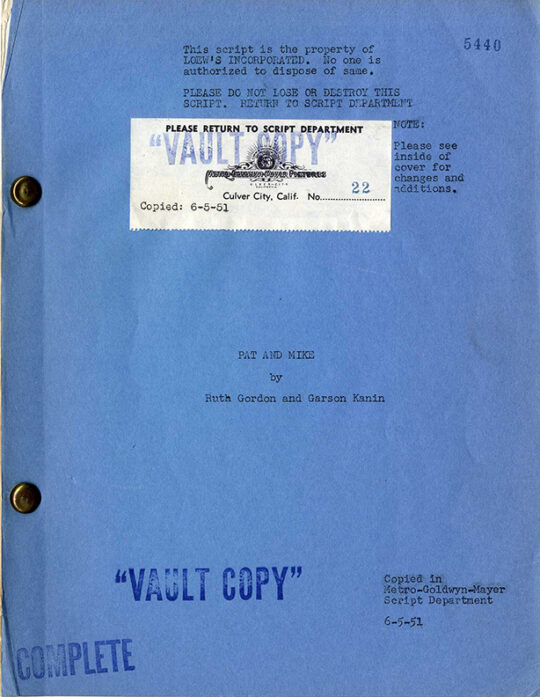

PAT AND MIKE (Jun 6, 1951) Film script by Ruth Gordon, Garson Kanin

$2,500.00 Add to cart