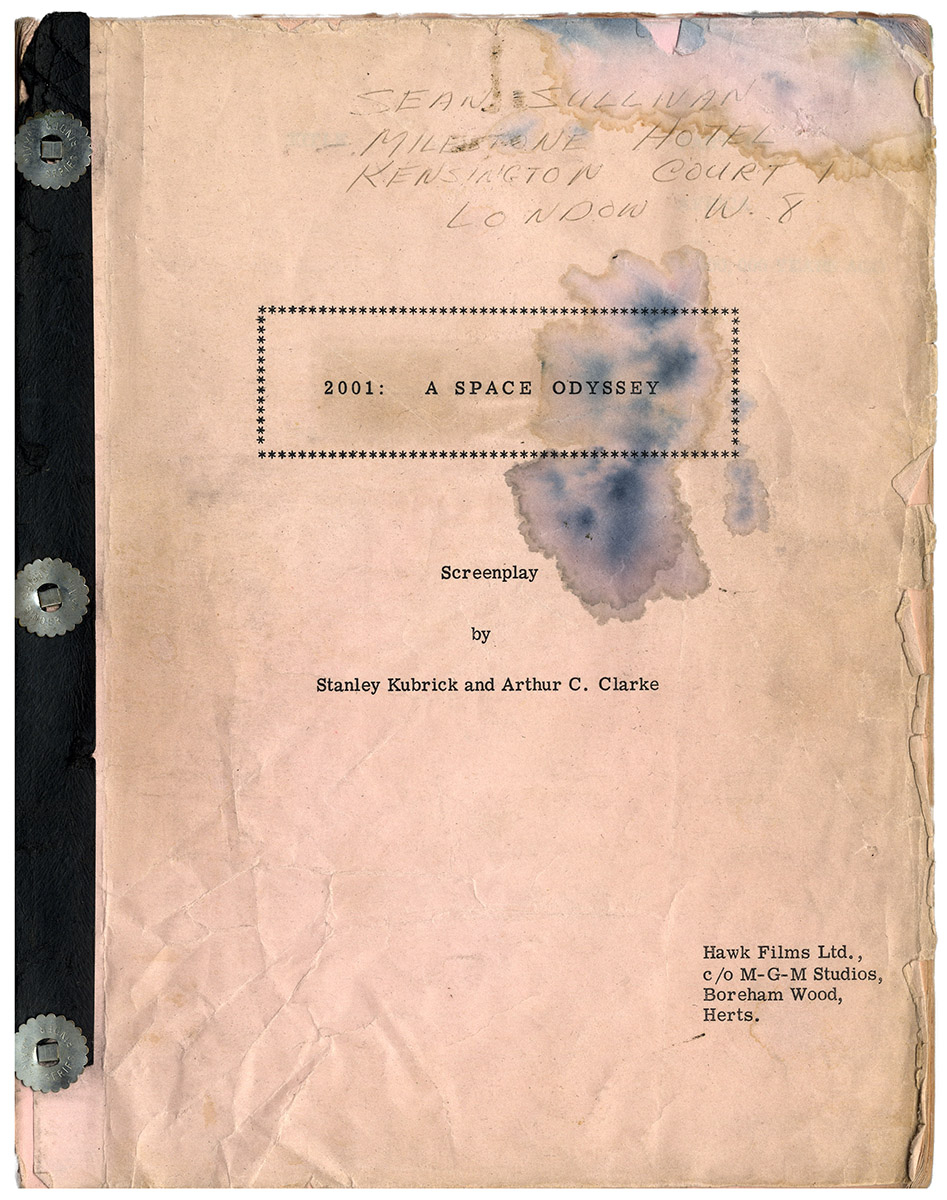

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1965) Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke

Boreham Wood, Hertfordshire, [U.K.]: Hawks Films Ltd., 1965. Mimeographed script, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.), bound with three metal clasps. Self-wrappers, staining to title page (and increasingly light stains to the following ten pages), light chipping to title page and to back wrapper. Back wrapper has various tears and is repaired in one place with tape. Overall a solid very good script.

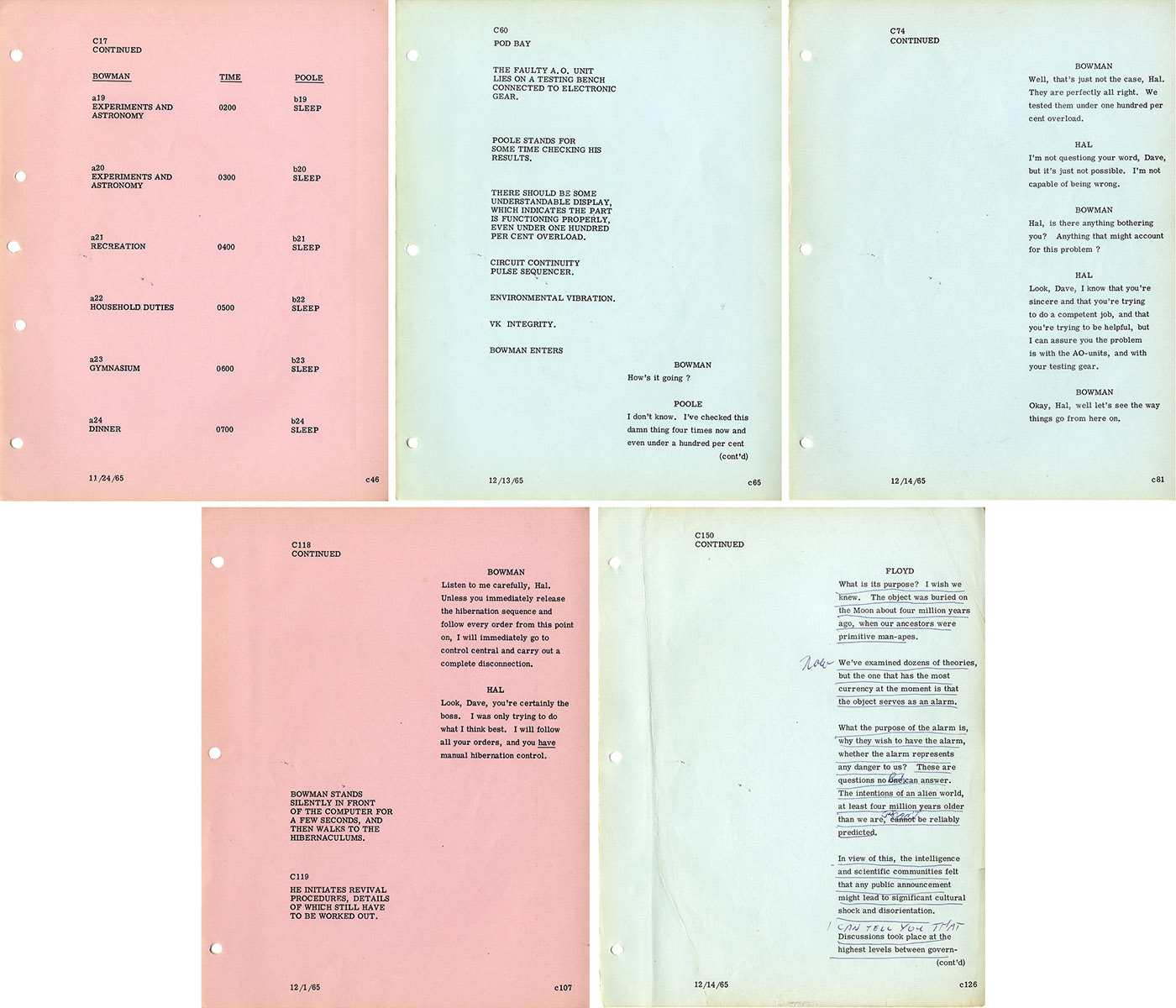

This script belonged to actor William Sylvester, who was third-billed in the role of Dr. Heywood R. Floyd. In this draft of the film, Sylvester had a much larger role than in the final film, including extensive dialogue which Kubrick eventually did not choose to use. He has underlined and sometimes, for emphasis, also circled all of his lines, and he occasionally contributes a small change of dialogue or a word or two of comment about certain lines.

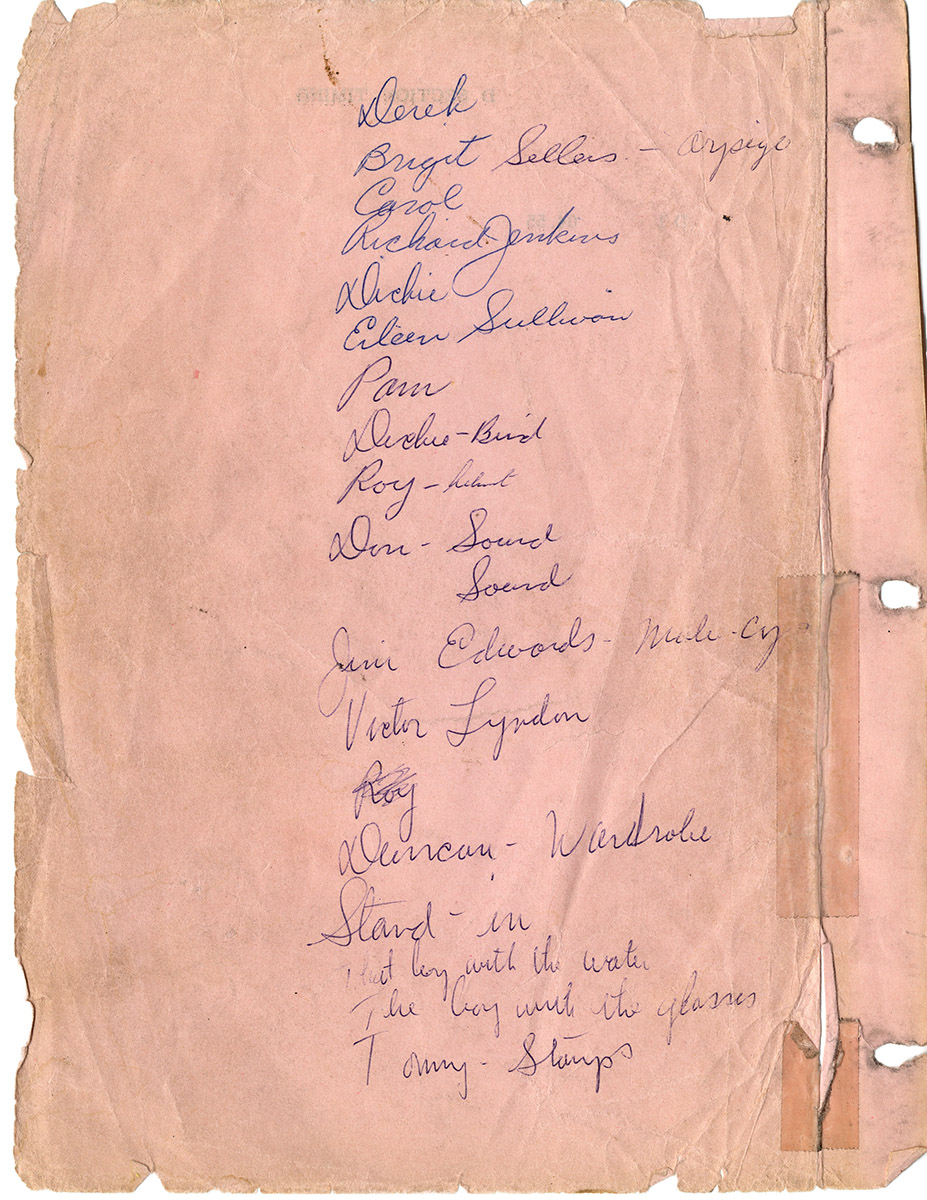

The script has written at the top of the title page the name and London address of Sean Sullivan, another actor who had the smaller role of Dr. Bill Michaels. On the outer back wrapper there is a list (in an unknown hand) of various people involved in the film’s production.

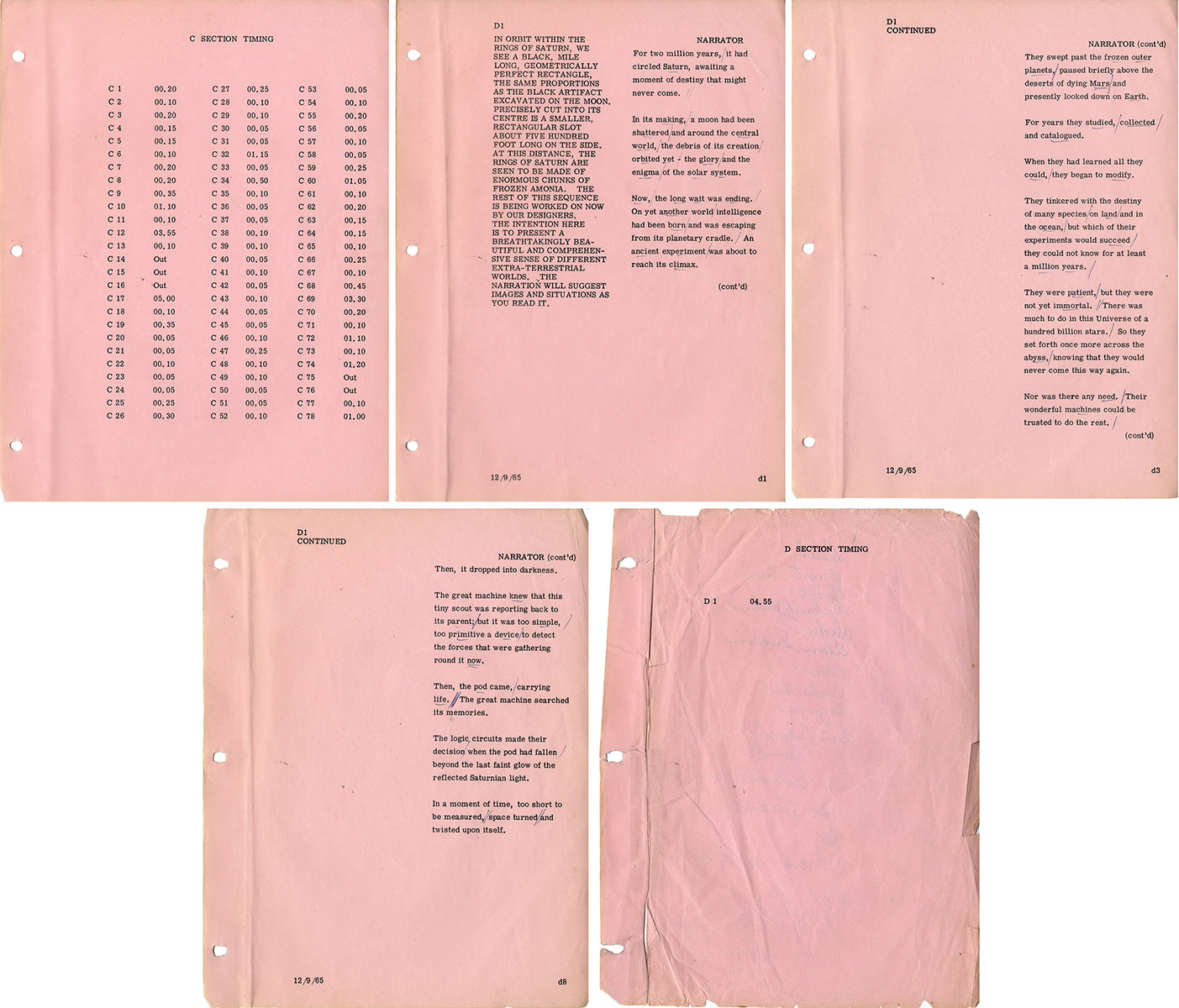

This composite screenplay by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, consisting of pink, green, and blue pages dated April 10, 1965 through December 14, 1965, shows the development of Kubrick’s epic science fiction masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey, from its earliest draft pages to the final stages of pre-production. Though written as a shooting script, even including the exact timing of individual sequences (principal photography began on December 29, 1965), it is nonetheless significantly different from the movie that was released in April 1968, a film that became more and more purely a non-verbal audiovisual experience as it approached its final form.

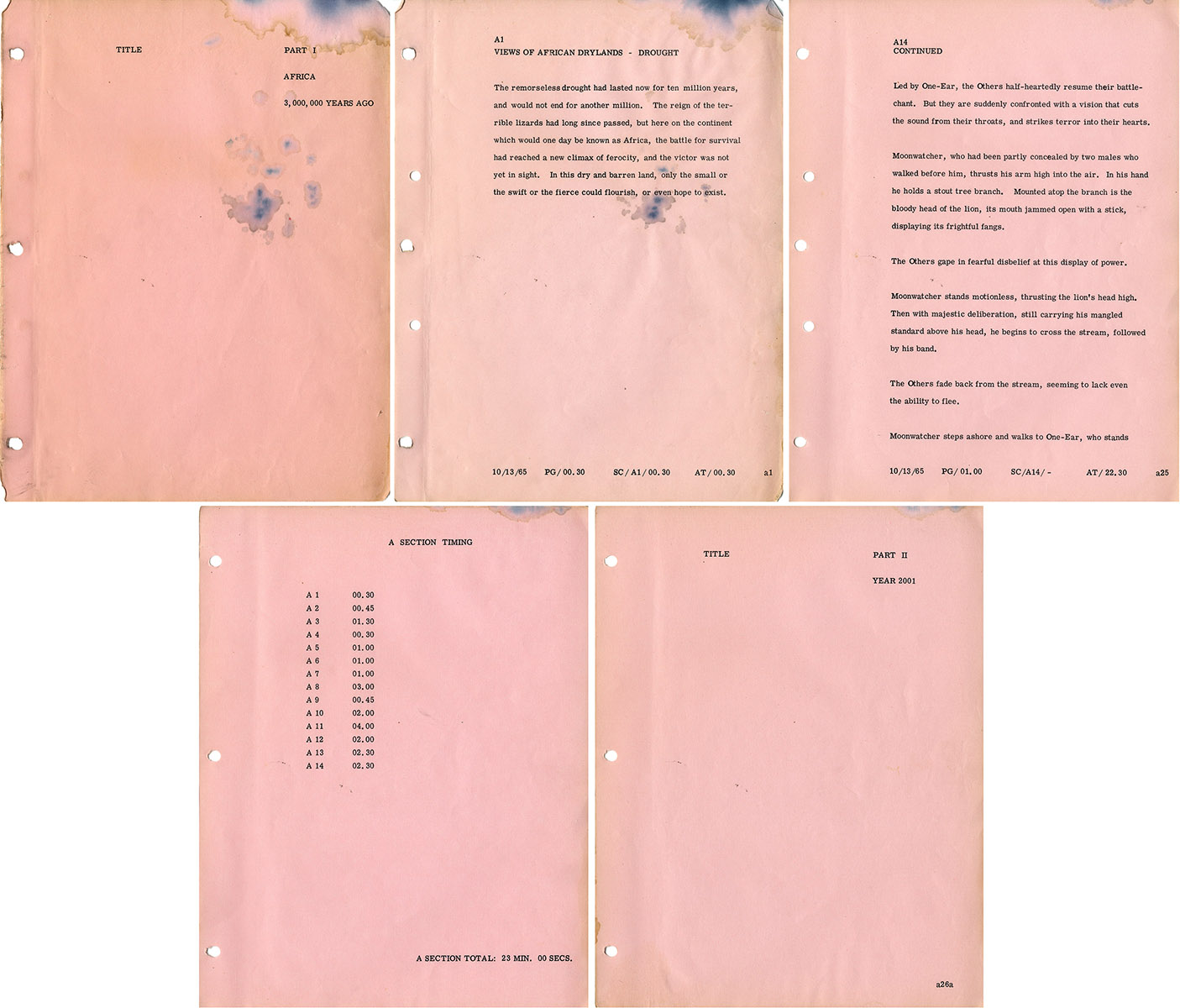

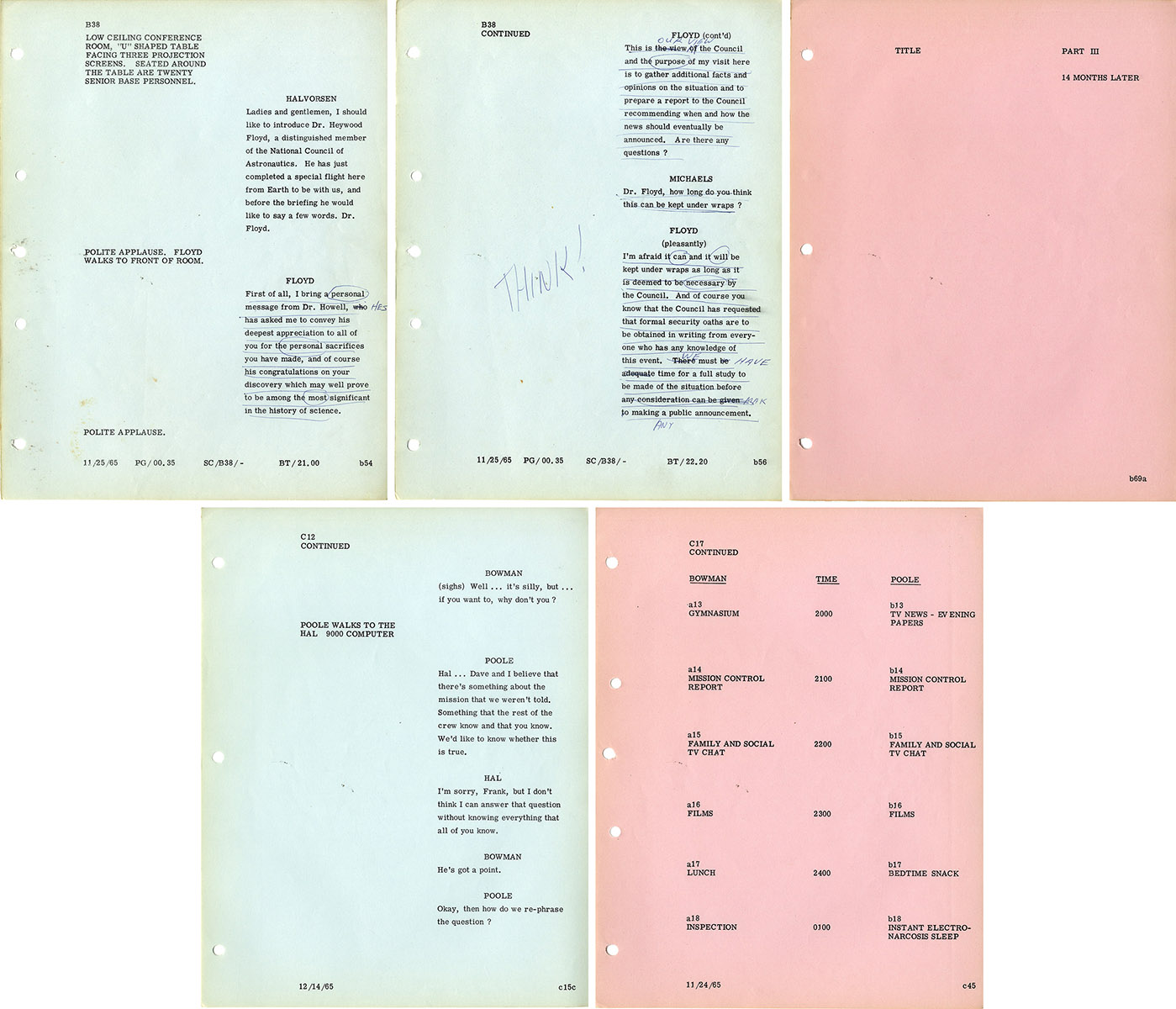

Kubrick’s groundbreakingly experimental film is divided into four sections or movements referred to as: (I) The Dawn of Man, (II) Mission to the Moon, (III) Mission to Jupiter, and (IV) Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite. The 1965 composite script is similarly divided into four parts: (A) Africa 3,000,000 Years Ago, (B) Year 2001, (C) 14 Months Later, and (D) Untitled. One major difference between the 1965 script and the completed film is that while the script relies heavily on voiceover narration to explain things, the completed film has no narration at all. The screenplay also has more dialogue than the completed film. Kubrick ultimately decided to let his images speak for themselves.

It was shortly after the January 1964 release of Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, a black comedy with science fiction overtones, that its director, Stanley Kubrick, decided his next project would be about contact with extraterrestrials. After reading the works of numerous science fiction authors, Kubrick approached British writer Arthur C. Clarke, whose 1953 novel Childhood’s End anticipates 2001 in many ways. Meeting for the first time at Trader Vic’s in New York on April 22, 1964, the two began discussing the project that would occupy the next four years of their lives.

Some of the differences between Kubrick and Clarke’s 1965 screenplay and the completed film are striking. For example:

PART A. AFRICA 3,000,000 YEARS AGO / THE DAWN OF MAN — This section describes what Kubrick and Clarke call “man-apes” and their first encounter with alien intelligence. This part of the screenplay reads like a Clarke short story, describing a tribe of man-apes living on an arid plain, and one in particular whom the screenplay refers to as “Moonwatcher”. The tribe is herbivorous and “slowly starving to death” since they have not yet learned how to hunt or kill. As in the movie, they are confronted from time to time by a tribe of “Others”. In the screenplay, the two rival tribes scratch and claw at each other. In the movie, they merely raise their arms threateningly and grunt. In the movie, extraterrestrial intelligence arrives in the form of a black rectangular monolith. In the screenplay, somewhat differently, extraterrestrial intelligence arrives in the form of a completely transparent Crystal Cube which acts like a teaching machine, first attracting the man-apes’ attention with “spinning wheels of light”, then showing holographic pictures inside itself of the man-apes using stones as weapons and killing warthogs for food. In the movie, there is no explicit teaching by the extraterrestrial object; we simply see the man-apes approaching and touching the black humming monolith, and some days later, we see Moonwatcher, whose brain has been stimulated by the close encounter, apparently figuring out on his own how to use a thigh bone as a weapon and then showing the rest of his tribe how to use these weapons to prey on meat animals and to kill the rival Others (“He had taken his first step towards humanity”). In the movie, this section ends with Moonwatcher throwing the thigh bone in the air and — in one of the most famous transitions in cinema history — the film abruptly cuts to a similarly shaped vehicle hovering in space 3 million years in the future. Nothing in the 1965 screenplay hints at this spectacular transition.

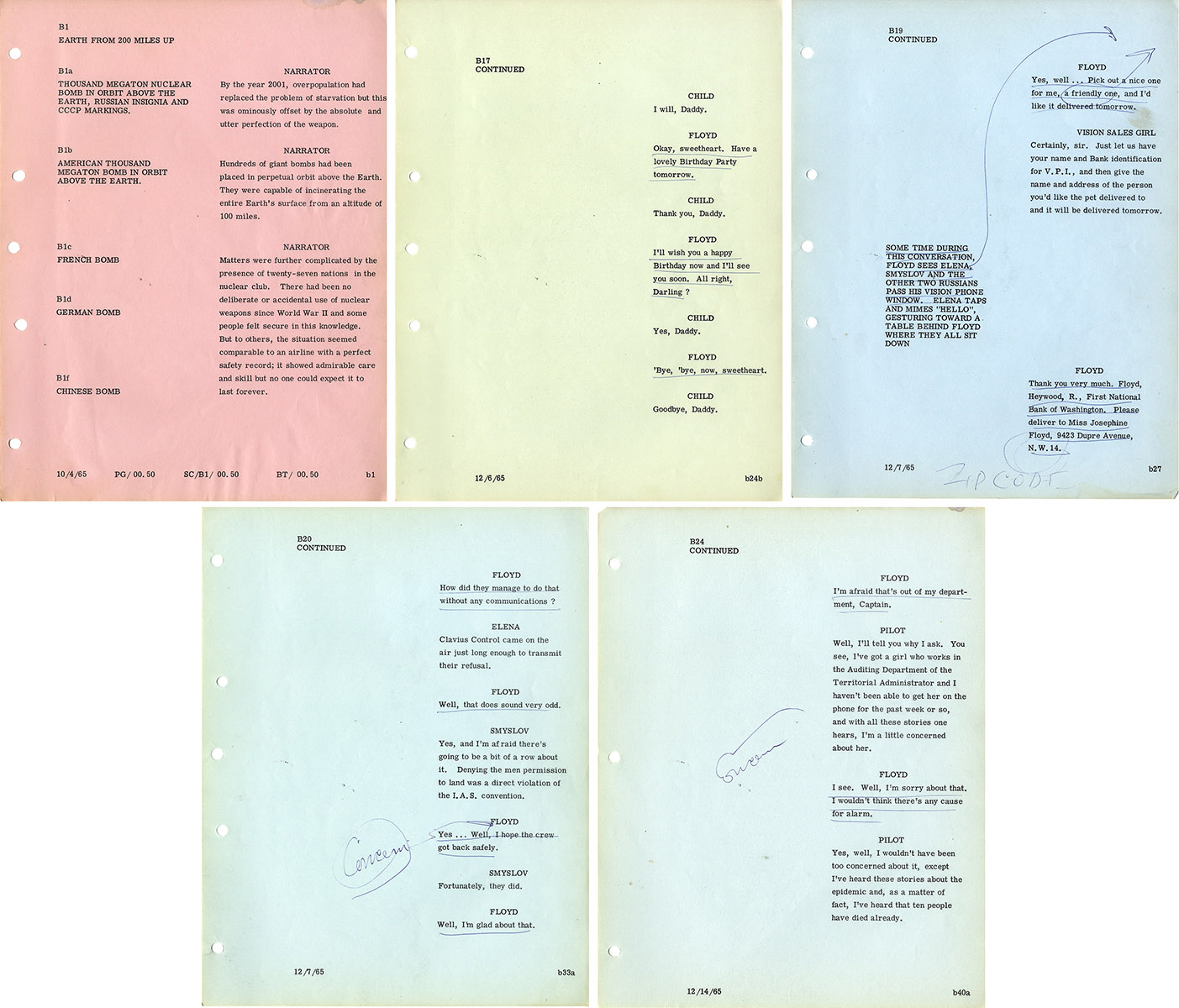

PART B. YEAR 2001 / MISSION TO THE MOON — This section of the screenplay, unlike the movie, begins with images of nuclear bombs orbiting the Earth. In the film, there are no references to nuclear weapons. Instead, there is an extended wordless sequence of a passenger rocket docking at a space station, choreographed to the music of Strauss’ Blue Danube waltz.

Then, in both script and film, we are introduced to Dr. Heywood Floyd, an American scientist on his way to the Moon. In both screenplay and film, we see Dr. Floyd engaging with flight personnel, making a video phone call to his daughter on Earth, and bantering with a group of suspicious Russian scientists aboard the station. Although the dialogue in these exchanges is somewhat different in the film, in both screenplay and film the dialogue is intentionally banal (to contrast with the futuristic wonders of the space setting).

In the second part of this section, Dr. Floyd takes a shuttle from the space station to the Moon crater Clavius, where he and other space-suited men examine an implanted alien object like the one in Part A of the story (the screenplay refers to it as “Deep-Space-Monitor-79”). At which point the alien object emits a signal of some sort — “five electronic shrieks” in the screenplay — an overpoweringly loud hum in the film.

PART C. 14 MONTHS LATER / MISSION TO JUPITER — This section introduces us to Bowman and Poole, two American astronauts piloting a spacecraft called Discovery One to Saturn in the screenplay, Jupiter in the film. They are accompanied by several other astronauts, asleep in hibernation chambers, and a sentient computer named HAL.

Unlike the film, in the screenplay the first dialogue between Bowman and Poole is a conversation about “salary cheques”. In a series of shots, described in the screenplay by only one or two words each, we see Bowman and Poole engaging in various routine activities — SLEEP — GYMNASIUM — BREAKFAST — SHIP INSPECTION – HOUSEHOLD DUTIES — TV NEWS — LUNCH. The computer HAL reports that a critical part is about to fail, but when Poole takes a space pod outside the ship to inspect the part, he discovers nothing wrong. Here the screenplay and the movie diverge. In one of the movie’s most memorable scenes, Bowman and Poole go inside a pod, knowing they can’t be heard, to discuss what might be wrong with HAL — but not knowing that HAL can read their lips through the window of the pod! There is no equivalent scene in the screenplay. However, in both screenplay and film, HAL remotely controls a pod to murder Poole when he goes outside the ship again to inspect the allegedly failing part.

Knowing that an angry Bowman intends to dismantle HAL, HAL now tries to murder Bowman and the hibernating crew, but Bowman wins the battle of man vs. machine and succeeds in neutralizing HAL (the iconic scene of a dying HAL singing “Daisy, Daisy” is in the screenplay as well as the film). Only then does Bowman learn the real purpose of his mission — to follow and investigate the signal sent from the alien artifact on the Moon to its planetary destination.

PART D. UNTITLED / JUPITER AND BEYOND THE INFINITE — This portion of the screenplay, mostly philosophical narration, only 8 pages long, gives hardly any idea of what was eventually filmed. It starts by describing a large black alien artifact floating in space, like the one found on the Moon, but it doesn’t say what happens to Bowman when he meets the object. Clearly, this was something left to be worked out between Kubrick and his special effects crew after the completion of the 1965 script.

In the film, but not in the screenplay, Bowman passes through a “Star Gate”, a tunnel of psychedelic lights, and ends up in a neoclassical bedroom where, observed by the bodiless extraterrestrials, he rapidly ages, dies, and is reborn as a fetus floating above Earth in an orb. Kubrick later explained the film’s concluding sequence as follows:

“In a timeless state, his life passes from middle age to senescence to death. He is reborn, an enhanced being, a star child, an angel, a superman, if you like, and returns to earth prepared for the next leap forward of man’s evolutionary destiny.”

Collation: [title], “TITLE PART I” (pink, nd), a1-a26 (pink, 10/13/65), “A SECTION TIMING” (pink, nd), a26a (“TITLE PART II”) (pink, nd), b1-b5 (pink, 10/4/65), b6 (blue, 10/4/65), b7-b11 (pink, 10/4/65), b12-b13a (green, 12/7/65), b14-b18 (blue, 12/7/65), “PAGES b19-b22 DELETED” (blue, 12/7/65), b23-b24b (green, 12/6/65), b25-b27a (blue, 12/7/65), b28 (green, 12/7/65), b29-b33d (blue, 12/7/65), b34 (pink, 10/4/65), b34a-b36 (blue, 12/6/65), b37 (pink, 10/4/65), b39-b40b (green, 12/14/65), b41-b51 (pink, 10/4/65), b52-b53 (pink, 10/5/65), b54-b56a (blue, 11/25/65), b57 (pink, 10/5/65), b58-b59 (blue, 11/25/65), b60 (blue, 12/14/65), b61 (pink, 10/5/65), b62 (green, 12/14/65), b63-b69 (blue, 11/25/65), “B SECTION TIMING” (pink, nd), b69a (“TITLE PART III”) (pink, nd), c1-c11 (pink, 11/19/65), c12-c15f (blue, 12/14/65), c16 (pink, 11/19/65), c16 (pink, 11/19/65), “PAGES c17-c41 DELETED” (blue, nd), c42-c47 (pink, 11/24/65), c48-c52 (c53 DELETED) (blue, 12/13/65), c54 (pink, 11/24/65), c55-c58 (blue, 12/13/65), c59-c64 (pink, 11/24/65), c65-c65a (blue, 12/13/65), c66 (pink, 12/1/65), c67-c69 (blue, 12/13/65), c70 (pink, 12/1/65), c71-cc7 (c73 DELETED) (blue, 12/13/65), c74 (pink, 12/1/65), c75 (blue, 12/14/65), c76-c79 (pink, 12/1/65), c80-c83 (blue, 12/14/65), c84-c85 (pink, 12/1/65), c86-c91 (blue, 12/14/65), c92-c100 (pink, 12/1/65), c101-c107 (blue, 12/14/65), c107-c118 (pink, 12/1/65), c119-c128 (blue, 12/13/65), “C SECTION TIMING” (pink, nd), “C SECTION TIMING (CONTINUED)” (pink, nd), d1-d8 (pink, 12/9/65), “D SECTION TIMING” (pink, nd).

Out of stock

Related products

-

![LES CREATURES [THE CREATURES] (1966) French film script](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/LesCreaturesSCR_a-540x689.jpg)

Agnès Varda (screenwriter, director) LES CRÉATURES (1966) Film script

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

![[Doyle, Arthur Conan (source work)]: "SHERLOCK HOLMES FIGHTS BACK" [released as: SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SECRET WEAPON] 22 May - 17 June 1942](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/SherlockHolmesFightsBack-Script1-540x724.jpg)

SHERLOCK HOLMES FIGHTS BACK [released as SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SECRET WEAPON] (May 22-Jun 17, 1942) Screenplay

$2,000.00 Add to cart -

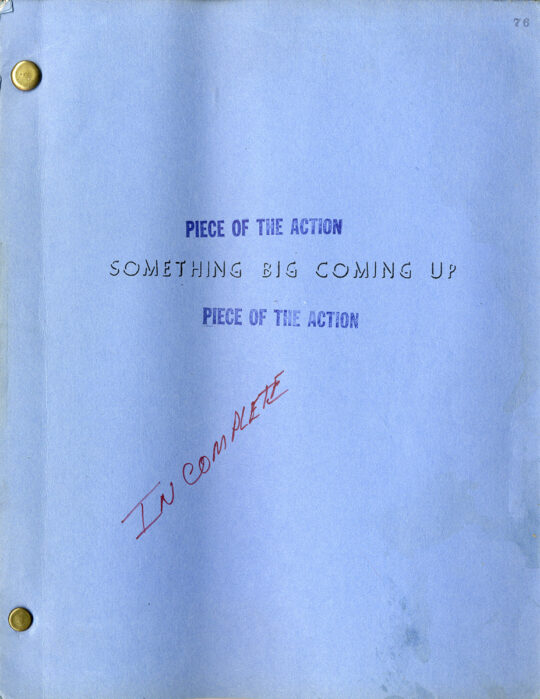

(African American film) A PIECE OF THE ACTION [working title: SOMETHING BIG COMING UP] (Nov 1, 1976) Film script

$750.00 Add to cart -

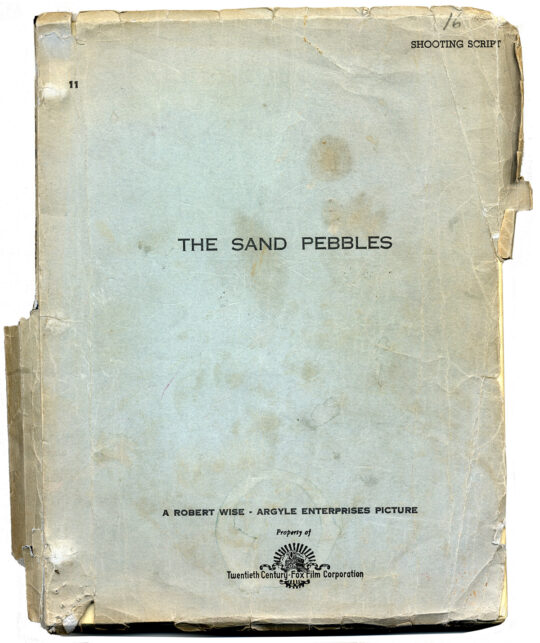

SAND PEBBLES, THE (Nov 1, 1965) Shooting script by Robert Anderson

$1,150.00 Add to cart