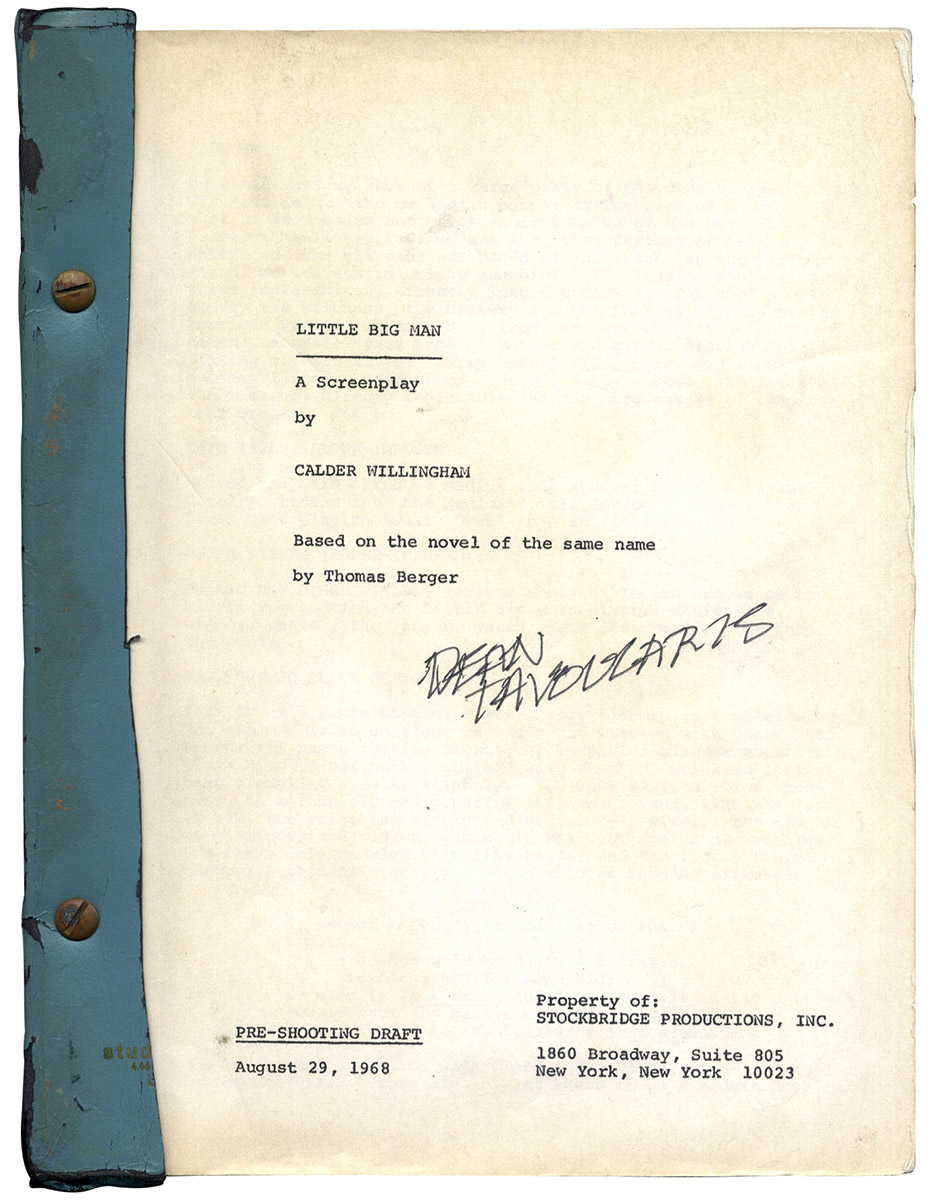

LITTLE BIG MAN: A Screenplay by Calder Willingham, Based on the Novel… by Thomas Berger (1968) Pre-shooting draft script

Arthur Penn (director) New York: Stockbridge Productions, 1968. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.),mimeograph, brad bound, 160 pp. The original leatherette covers from Studio Duplicating Service is mostly gone, with only a fragment of it at the spine and adjacent to the spine. Overall, very good.

This script is autographed by Dean Tavoularis, who was production designer for this (and so many other now legendary films); after designing Penn’s BONNIE AND CLYDE and this film, went on to design Francis Coppola’s THE GODFATHER I, II, and III, THE CONVERSATION, and APOCALYPSE NOW, among many others.

LITTLE BIG MAN was an epic, picaresque Western brought to the screen by the accomplished theater, television, and film director Arthur Penn (1922-2010). It was the second of three films made by Penn in the Western genre — the other two being THE LEFT-HANDED GUN (1958) and THE MISSOURI BREAKS (1976). It was one of a series of revisionist “anti-Westerns” made by Hollywood in the 1960s and 1970s, films that critiqued the conventions of the genre, in particular, the way the genre had traditionally treated Native Americans. It is also a movie that appears to intentionally recall two of the most popular and influential counter-cultural films of the 1960s, Mike Nichols THE GRADUATE (same male star, Dustin Hoffman, and same screenwriter), and Arthur Penn’s own BONNIE AND CLYDE (same female star, Faye Dunaway, and same director).

Like BONNIE AND CLYDE and many of Penn’s other movies, LITTLE BIG MAN was a film of mixed tones, combining raucous comedy and social satire with sequences of serious grisly violence.

This screenplay adaptation of Thomas Berger’s novel was by Georgia-born Calder Willingham (1922-1995) whose prior screen credits — in addition to THE GRADUATE — included Jack Garfein’s THE STRANGE ONE (based on Willingham’s novel) (1957), Stanley Kubrick’s PATHS OF GLORY (1957), David Lean’s THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI (1957), Richard Fleischer’s THE VIKINGS (1958), and Marlon Brando’s ONE-EYED JACKS (1961).

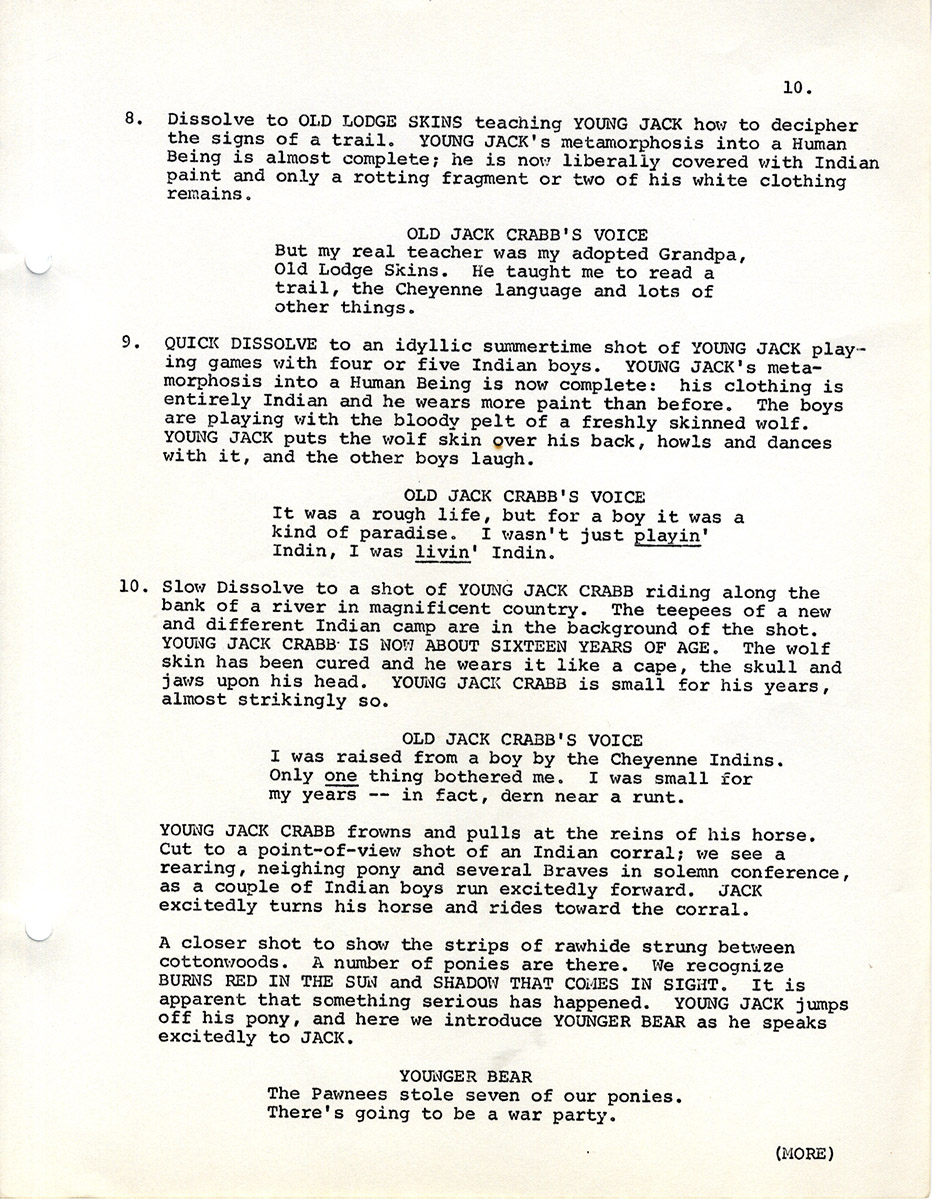

Willingham’s “Pre-Shooting Draft” screenplay includes most of the dialogue, characters, and incidents that appear in the completed movie. The script is heavily dependent on the first-person narration of its central character (Dustin Hoffman), much of which is borrowed directly from Berger’s novel. However, the screenplay has been considerably edited, tweaked, and polished in its transition from 1968 shooting script to 1970 film.

One of the most obvious examples of how the script was revised is the way it opens. The screenplay opens with images of the Cheyenne braves and the Cavalry soldiers who oppose them just before the Battle of the Little Big Horn — foreshadowing the story’s climax. This is followed by our introduction to 121-year-old Jack Crabb (Hoffman), the “sole white survivor” of the Little Big Horn, who narrates the story as he is being interviewed in our present.

The movie dispenses with the introductory images of Indians and Cavalry and, instead, begins directly with a black screen and the voice of Jack Crabb speaking to his interviewer. The dialogue between 121-year-old Jack Crabb and the interviewer has also been substantially revised. The dialogue in the screenplay is comparatively innocuous, with the interviewer mainly expressing his skepticism regarding Crabb’s actual presence at the Battle. The dialogue in the filmed version of the same scene is considerably more pointed, with the interviewer characterizing Jack’s story as “tall tales” (letting the audience know what the tone of the film will be) and explicitly referring to the “genocide” of Native Americans (establishing one of the film’s central themes). In the movie, but not the screenplay, Jack tells the interviewer to shut up and turns on the tape recorder himself, firmly establishing his control of the narrative.

The ending was similarly revised. The screenplay ends with the last incident of Jack’s flashback, he and his Native American father figure “Old Lodge Skins” (Chief Dan George) climbing a ridge to the place to where the old Chief thinks he is going to die. (The death does not occur. “Sometimes the magic works. Sometimes it doesn’t,” says the Chief.) The movie ends with a coda to the flashback, taking us back to the present, with 121-year-old Jack Crabb turning off the tape recorder and staring into the darkness.

Rather than a traditional three-act structure, the screenplay is structured as a series of almost-random episodes in the life of Jack Crabb, split between the white and Native American cultures — Jack as a white boy captured and raised by the Cheyenne, Jack as a teenager adopted by a preacher and his randy wife (Faye Dunaway), Jack as an assistant to a snake-oil salesman (Martin Balsam), Jack as a gunslinger, Jack as a merchant married to a Swedish woman, Jack returning to the Indians who raised him, Jack as a mule skinner working for General Custer until Custer and his troops massacre an Indian village, Jack as a trapper having turned his back on people altogether (changed in the movie from “trapper” to “hermit”), Jack returning to his Native American friends, this time acquiring an Indian wife and family until an even more horrible massacre by the Cavalry, Jack finally returning to General Custer and participating in his defeat by Native Americans at the Little Big Horn.

The main structural principal is that Jack encounters every important character twice over a period of many years — two sequences involving his older sister, two erotic sequences involving the preacher’s wife (in the second sequence she has become a prostitute working in a brothel), two sequences with the snake-oil salesman, two sequences with Wild Bill Hickok, two main sequences with General Custer, and so on.

This is one of filmmaker Penn’s most explicitly counter-cultural films. Traditional heterosexuality is contrasted with a gay Native American character, fully accepted by the Cheyenne society, and traditional white monogamous marriage is contrasted with polygamy when Jack briefly has three additional Native American wives (sisters of his chosen wife whose husbands were killed). Most significantly, the film contrasts white and Native American attitudes toward nature and life — “The Human Beings [the Cheyenne] believe that everything is alive. Not only men and animals, but water and earth and stones . . . . But white men believe that everything is dead. Stones, earth, animals and people, even their own people. If things persist in trying to live, white men will rub them out. That is the difference between white men and Human Beings.”

Out of stock

Related products

-

LOOT (ca. Sep 1969) Final Draft screenplay

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT, A (1987) Larry Cohen-signed script

$625.00 Add to cart -

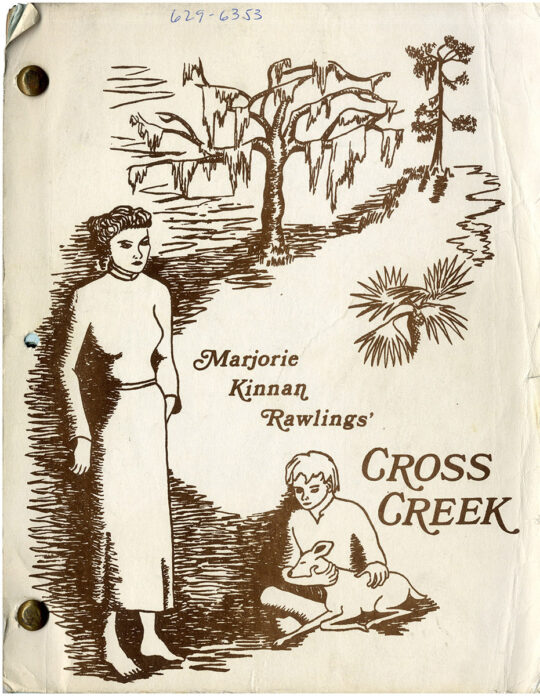

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart -

DRESS GRAY (Mar 6, 1981) Second revision script by Gore Vidal

$500.00 Add to cart