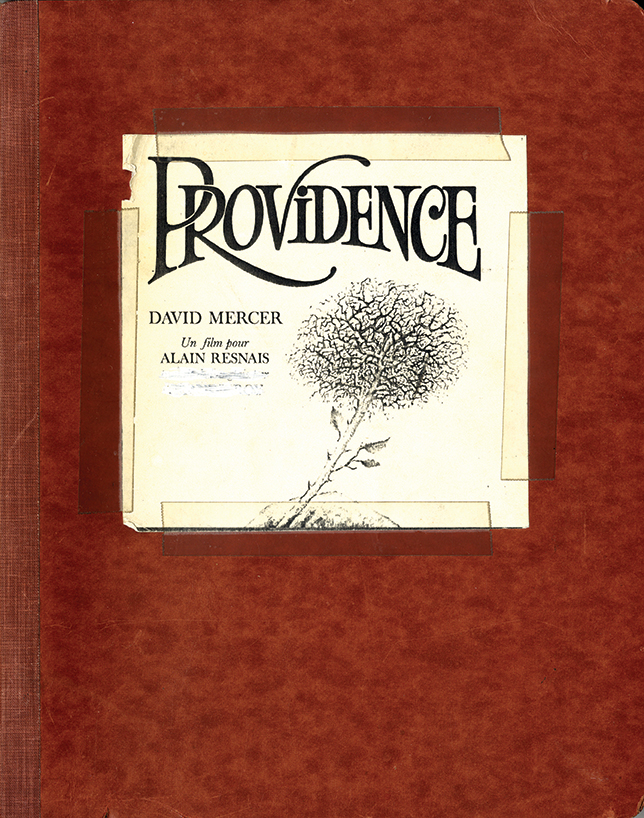

PROVIDENCE (1977) Final 3rd draft film script by David Mercer, ca. 1975

Final (3rd) Draft film script, London, [ca. 1975]. Vintage original film script, quarto. Generic brown card report wrappers bound with matching brown cloth and an internal clasp binding. With a homemade photocopied title label that credits ALain Resnais and David Mercer, and a credit for an English translator that is interestingly whited out. 82 leaves, with last page of text numbered 75. Second generation photocopy, but made during production, with holograph annotations throughout as noted above. NEAR FINE.

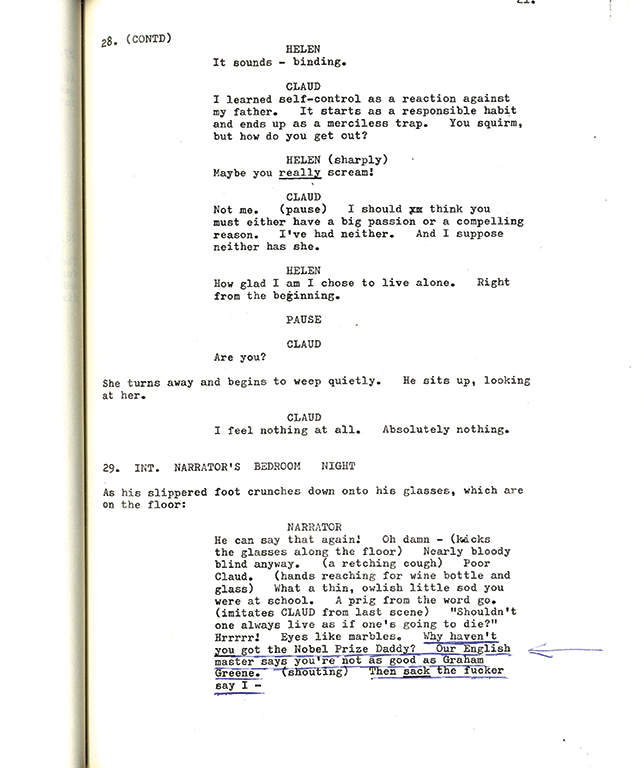

Noted British playwright and screenwriter David Mercer’s copy, with his copied typeovers and holograph ink annotations throughout, both mostly with regard to emended dialogue.

For some viewers, PROVIDENCE is the greatest film made by director Alain Resnais (1922-2014), high praise to be sure, given that the French auteur also directed NIGHT AND FOG (1956), HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR (1959), LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD (1961), MURIEL (1963), LE GUERRE EST FINIE (1966), and other groundbreaking classics of the French New Wave. Resnais described PROVIDENCE as “a meta-film, a film about the making of films, a work of art about the fabricating of art works”. It swept the 1978 Césars (the French Oscars), including the awards for Best Director, Best Editing, Best Music (Miklós Rózsa), Best Writing, and Best Film.

PROVIDENCE was Resnais’ first film in English, based on a screenplay by David Mercer (1928-1980). Mercer began his career as a British television dramatist with the trilogy, THE GENERATIONS, composed of WHERE THE DIFFERENCE BEGINS (1961), the anti-nuclear piece A CLIMATE OF FEAR (1962), and THE BIRTH OF A PRIVATE MAN (1963). His 1962 teleplay A SUITABLE CASE FOR TREATMENT became the film MORGAN (Karel Reisz, 1966) starring David Warner – who later appears as one of the five stars of Resnais’ PROVIDENCE. Mercer soon became a successful playwright, whose works for the stage included THE GOVERNOR’S LADY (1965), RIDE A COCK HORSE (1965), BELCHER’S LUCK (1966), FLINT (1970), AFTER HAGGERTY (1970), DUCK SONG (1974), and COUSIN VLADIMIR (1978).

Mercer’s introduction to his screenplay summarizes what we are about to read as follows:

A distinguished and much-honoured old writer – CLIVE LANGHAM the NARRATOR of the film – is dying.

Haunted by the slow decay of his body and the insidious progress towards death, he struggles to imagine his final piece of work: a novel in which he explores aspects of himself through his son CLAUD and the way he imagines his son . . . .

What the dying writer imagines over the course of one painful night – part novel, part nightmare, in constant process of revision – incorporates his children and deceased wife as characters. The screenplay and film end the following day with a birthday celebration for the old writer in which we see the living characters as they really are. The movie stars John Gielgud as the writer, Clive Langham, Dirk Bogarde as his attorney son, Claud, Ellen Burstyn as his daughter-in-law, Sonia, David Warner as his bastard son, Kevin, and Elaine Stritch as his deceased wife, Molly (who appears in the imagined novel-within-the-film as Claud’s mistress).

The scenario also has a sociopolitical aspect. The scenes of family conflict are intercut with imagined scenes of what is going on in the country as a whole – apparently a fascist takeover of some kind, with people being rounded up and brought to a stadium.

The title, PROVIDENCE, derives from Providence, Rhode Island, birthplace and home of horror writer H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), a Resnais favorite. The film’s César-winning production designer, Jacques Saulnier, says Resnais made him read Lovecraft in order to imbue Langham’s house with the presence of death, “I imagined it like a family tomb”. Thus, amid the brittle drawing room comedy and political allegory there are touches of horror, e.g., characters who are turning into werewolves.

Resnais was known for being scrupulously faithful to the texts of his screenwriters, and PROVIDENCE is no exception. David Mercer’s dialogue is consistently sharp and laced with Wildean wit. At one point in his nighttime monologues, old Langham notes:

It’s been said about my work that the search for style has often resulted in a want of feeling… However I’d put it another way. I’d say that style is feeling. In its most elegant and economic expression.

The character is, of course, speaking for himself, but he could also be speaking for Mercer and Resnais. In a similar vein, Langham’s attorney son, Claud (Dirk Bogarde), asks:

CLAUD

Do you approve of violence Miss Boon?

MISS BOON

Certainly not.

CLAUD

Neither do I. It reeks of spontaneity.

However, fidelity to the screenwriter’s words doesn’t necessarily mean that what one reads on the page corresponds exactly to what one sees on the screen. Resnais had no problem cutting up and rearranging his writers’ texts… and adding imagery of his own. Mercer’s screenplay opens with a shot of a helicopter “circling the twin towers of a church”, followed by a shot of Claud in the courtroom:

CLAUD

Surely the facts are not in dispute?

In the movie, the shots of the helicopter and Claud prosecuting in the courtroom are preceded by a minute and a half of pure Resnais imagery, a series of tracking shots – part Lovecraft, part CITIZEN KANE – that take us closer and closer to the mansion where the old writer lays dying, then a shot of the old writer’s hand tipping over a wineglass with him saying “Damn! Damn! Damn!” that is transposed from later in the screenplay.

Resnais loved architecture and at one time published a book of his architectural photographs (Repérages, 1974). Reflecting that interest, the movie PROVIDENCE is filled with shots of impressive architecture, although there is nothing in the screenplay that would lead the reader to anticipate those shots.

Another addition – a shot of Kevin (David Warner) draping a banner that says “A Person Should Have the Right to Die as He Chooses” around the columns of what looks like a government building. This comes shortly before a scene – which does appear in the screenplay – where Kevin enters a room with his face bloodied. The screenplay directions indicate that he has been mugged, but in the movie – since we have just witnessed Kevin draping his political protest banner – we assume he was assaulted by soldiers or police who did not approve of his protest.

Another significant revision involving Kevin – the screenplay indicates he is Langham’s grandson; in the movie, he is Langham’s bastard, i.e., Claud’s half-brother, a change apparently made because it was more sensible given the ages of the actors cast in the key male roles (Gielgud, Bogarde, and Warner).

One of the most surprising things in this magnificent screenplay and film is the last scene, the outdoor family birthday celebration on the day following Langham’s dark night of the soul, surprising because after so much anxiety and regret it is so unexpectedly life-affirming.

Out of stock

Related products

-

LONG WALK HOME, THE (Oct 13, 1988) Second draft film script by John Cork

$375.00 Add to cart -

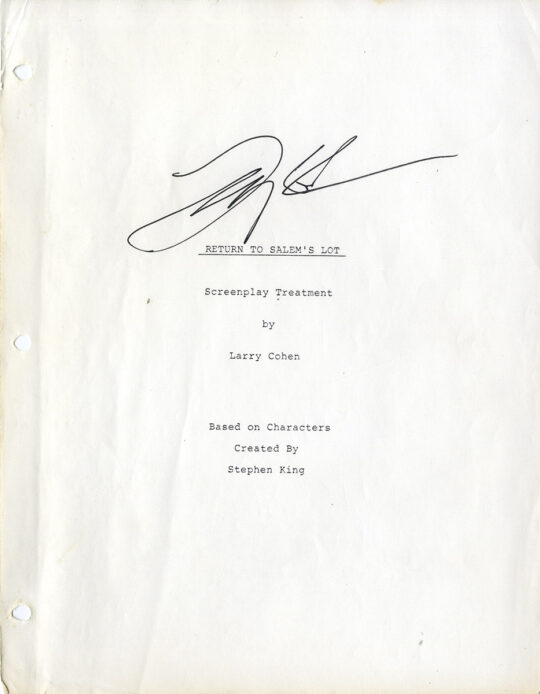

RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT, A (1987) Larry Cohen-signed archive

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

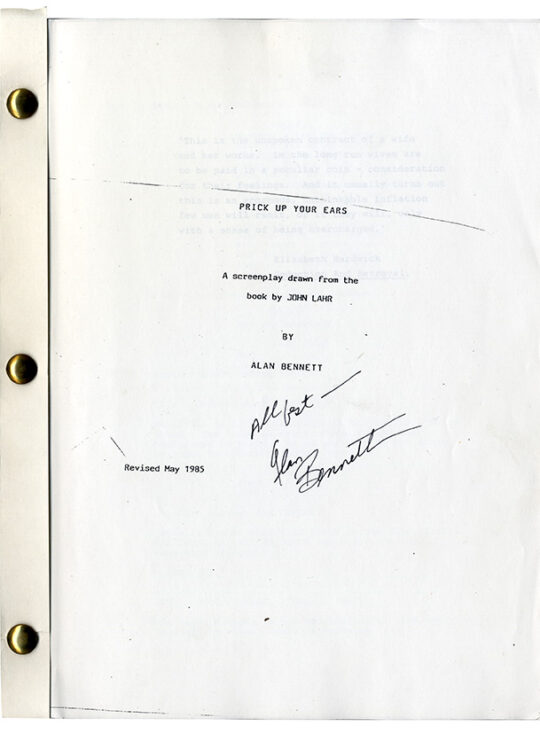

PRICK UP YOUR EARS (May 1985) Revised film script

$650.00 Add to cart -

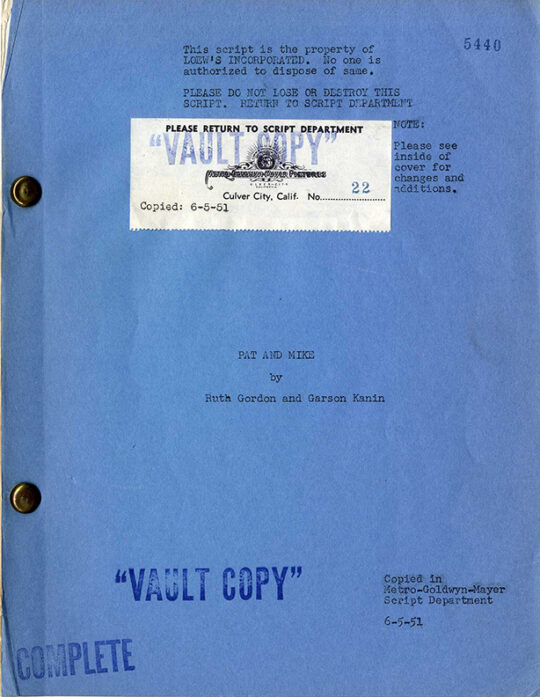

PAT AND MIKE (Jun 6, 1951) Film script by Ruth Gordon, Garson Kanin

$2,500.00 Add to cart