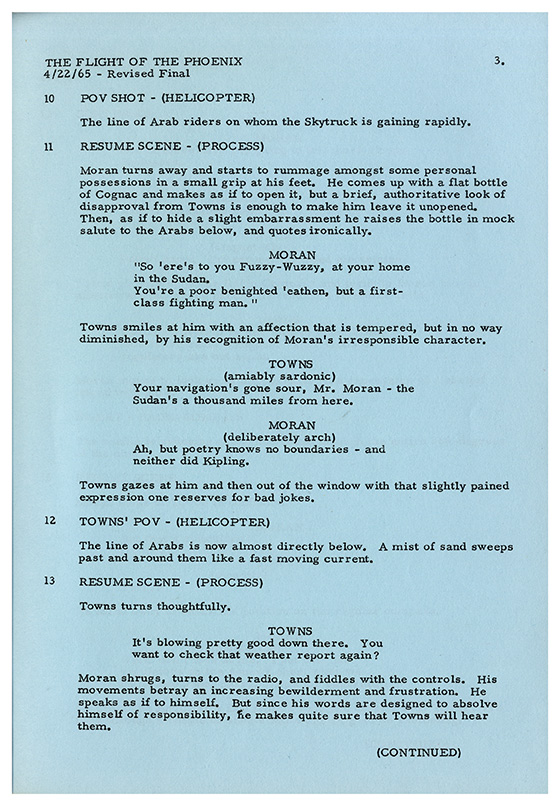

FLIGHT OF THE PHOENIX, THE (1965) Revised Final script dated Apr 6, 1965

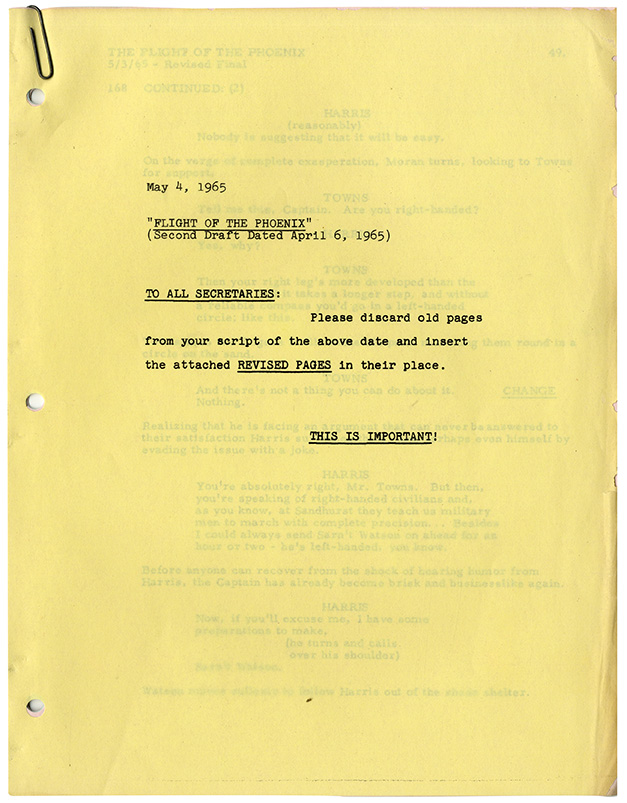

Robert Aldrich (director), Lukas Heller (screenwriter), Elleston Trevor (source) Vintage original screenplay by Lukas Heller from the novel by Elleston Trevor. Dated April 6, 1965, USA. With revisions on white and blue paper dated up through 4-22-65 [1], 159 pp., with 7 pp. of further revisions, dated May 4, laid in loosely. Printed studio wrappers, brad bound, yapped edges, mimeograph, quarto, moderate wear at edges of wrappers, JUST ABOUT FINE in VERY GOOD+ wrappers.

Producer/director Robert Aldrich (1918-83) was an auteur who loved to direct ensemble movies. His work is fairly divisible into mostly-female ensemble films — WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE?, HUSH HUSH SWEET CHARLOTTE, THE KILLING OF SISTER GEORGE — and mostly-male ensemble films — ATTACK!, THE BIG KNIFE, THE DIRTY DOZEN, ULZANA’S RAID, TWILIGHT’S LAST GLEAMING, THE CHOIRBOYS, and this one, THE FLIGHT OF THE PHOENIX, from a screenplay by Lukas Heller and based on a novel by Elleston Trevor (in two of the Aldrich films most admired by his fans, KISS ME DEADLY and THE LEGEND OF LYLAH CLARE, the ensemble is sexually diverse).

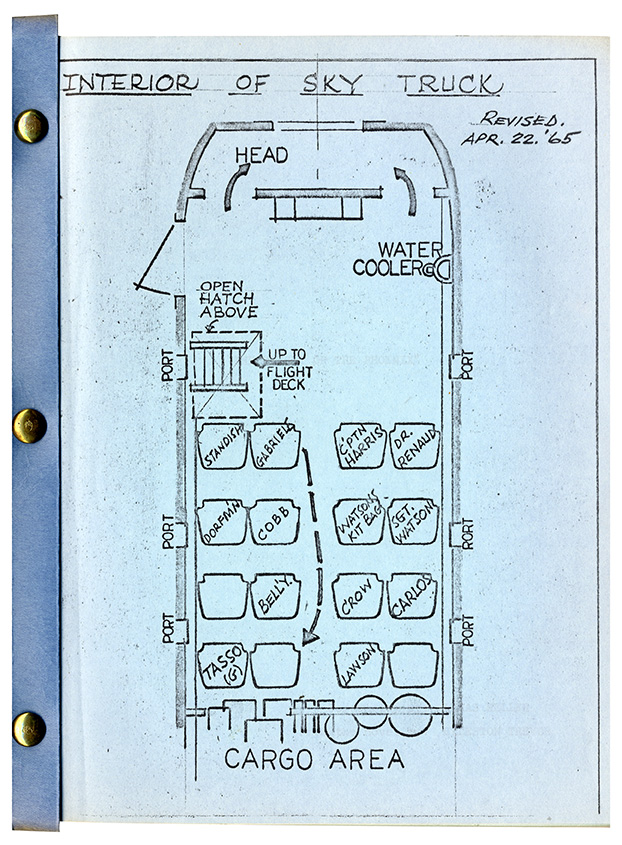

Like John Ford’s THE LOST PATROL and SEVEN WOMEN, and the majority of John Huston’s films, Aldrich’s THE FLIGHT OF THE PHOENIX is about the interactions of an eccentric group within a circumscribed environment, a “closed system ensemble movie.” The international cast of characters — twelve in all — stranded in the Arabian desert after their airplane crashes, includes a Lindbergh-like American pilot (James Stewart), his alcoholic British navigator (Richard Attenborough), a German aeronautical engineer (Hardy Kruger), a French psychiatrist (Christian Marquand) and his patient (Ernest Borgnine), a pair of British officers (Peter Finch as a Captain, and Ronald Fraser as his Sergeant), an American accountant (Dan Duryea), an Italian (Gabriele Tinti), a Latino (Alex Montaya), and some oil workers of varying nationalities (Ian Bannen – Scottish, George Kennedy – American, Peter Bravos – Greek). The only female “character” in the film is a belly dancer (Barrie Chase) hallucinated by the heat-stricken Sgt. Watson. It is the German engineer who comes up with the idea of building a smaller functional airplane (the Phoenix) out of the wreckage of the one that crashed. Hence, the film’s title.

This is one of Aldrich’s most political movies, with the internationalism of the ensemble giving the whole thing an allegorical flavor. The American pilot (Stewart) is a stubborn, go-it-alone, fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants, cowboy type. The German engineer (Kruger) is a cold, human-calculator type who insists that everything be done exactly his way — or not at all. The British navigator (Attenborough) is the desperate go-between who realizes the only hope for anyone’s survival is collective cooperation. The film’s political statement is as relevant today as when the film was made — the world must learn to cooperate or die.

Born in Germany to a Jewish family, screenwriter Lukas Heller (1930-1988) is best known for this and other Aldrich collaborations — WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE? (1962), HUSH HUSH SWEET CHARLOTTE (1964), THE DIRTY DOZEN (1967), THE KILLING OF SISTER GEORGE (1968), and TOO LATE THE HERO (1970). His non-Aldrich films include MONTE WALSH (1970) and DAMNATION ALLEY (1977).

Although this screenplay, at least its pink and blue pages, is designated the “Revised Final” version, there are significant differences between this draft and the completed movie. One striking example — this screenplay draft begins with an image of “Twelve Arab Riders” riding their camels across the desert near an oil camp, while on the soundtrack we hear “the faint drone of an airplane approaching.” Unlike the screenplay, there are no Arabs in the opening of the movie. The movie’s first image is that of a burning sun from which we pan down to a cargo plane taking off near a solitary oil pump. We get a shot of the plane’s shadow moving across the sand dunes, followed by a couple images of the plane in flight, from which we immediately cut to the plane’s interior, introducing us first to the pilot (Stewart), and then the other passengers. The screenplay’s first line is the navigator, quoting Kipling, “So ‘ere’s to you Fuzzy-Wuzzy, at your home in the Sudan …” The movie’s first line is one of the passengers asking the navigator, “Mr. Moran, are we going to be on time in Benghazi?”

Much of the character-establishing dialogue and business among the passengers in this pre-crash sequence was polished and reworked before filming — as was the remainder of the screenplay. Another significant difference — the movie adds an occasional voiceover from pilot Stewart (reminding us of similar voiceovers by Stewart playing a pilot in Billy Wilder’s THE SPIRIT OF ST. LOUIS) as he notes things like, “1350. Radio out of service.” These kind of off-hand references by star actors to their other screen roles crop up frequently in Aldrich films. See, for example, Davis and Crawford in WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE? and Kim Novak in THE LEGEND OF LYLAH CLARE.

The tour-de-force title montage sequence that accompanies the plane’s encounter with a sandstorm and resultant crash landing is indicated in the screenplay as “a Director’s Sequence of Quick Cuts and Frozen Frames that take in the last, timeless moments before the crash.” Two paragraphs in the screenplay provide the basis for two minutes of screen time. There was nothing like it until the title montage sequence of Sam Peckinpah’s THE WILD BUNCH four years later.

The story’s central conceit — building a new airplane from the wreckage of the old one — is beautifully and believably realized. Although there is no villain per se, the proud American pilot and the calculating German make formidable antagonists. Indeed, all of the screenplay’s characters and their dramatic interactions are effectively conceived.

Aldrich’s movies often depict humanity at its worst. The characters in his films, including this one, are prone to display varying degrees of egotism, greed, cowardice, pettiness, brutality and — especially! — insanity. Yet THE FLIGHT OF THE PHOENIX is one of the few Aldrich films to have a positive ending — the collective need to survive ultimately triumphs over neurotic individualism — and, in this case, the movie’s happy ending is fully earned.

The script’s first leaf is a diagram of the interior of the sky truck.

Out of stock

Related products

-

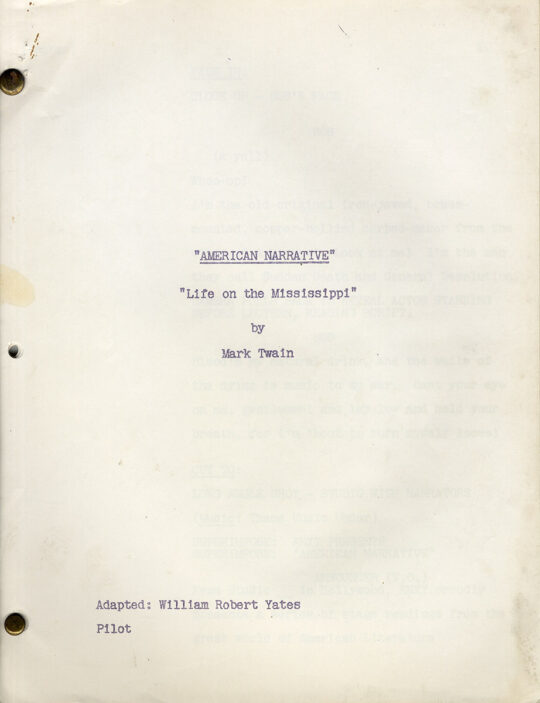

Mark Twain (source) LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI (ca. 1956) TV script adapted by William Robert Yates

$300.00 Add to cart -

![(Blaxploitation film) BLACK BELT JONES [1974] Film script by Oscar Williams](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/BlackBeltJonesSCR_a-540x693.jpg)

(Blaxploitation film) BLACK BELT JONES [1974] Film script by Oscar Williams

$500.00 Add to cart -

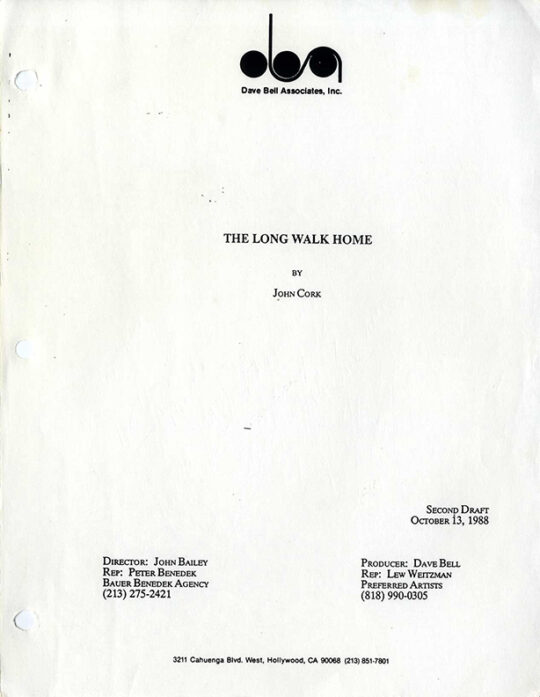

LONG WALK HOME, THE (Oct 13, 1988) Second draft film script by John Cork

$375.00 Add to cart -

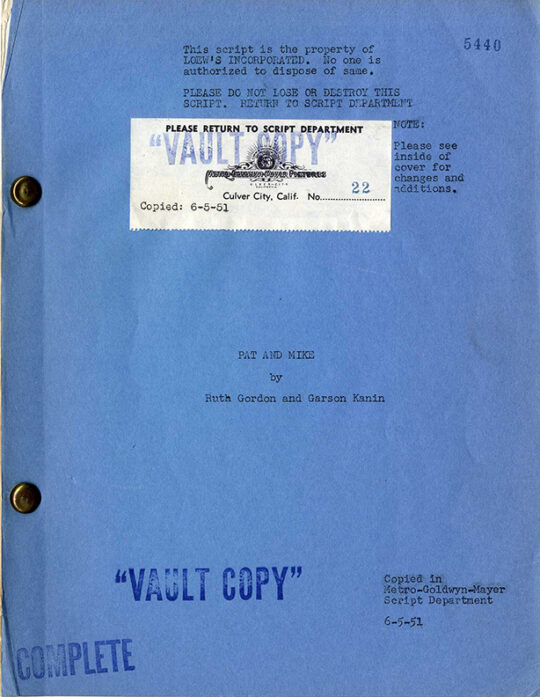

Ruth Gordon, Garson Kanin (screenwriters), George Cukor (director) PAT AND MIKE (Jun 6, 1951) Film script

$2,500.00 Add to cart