SERPICO (May 23, 1973) Film script

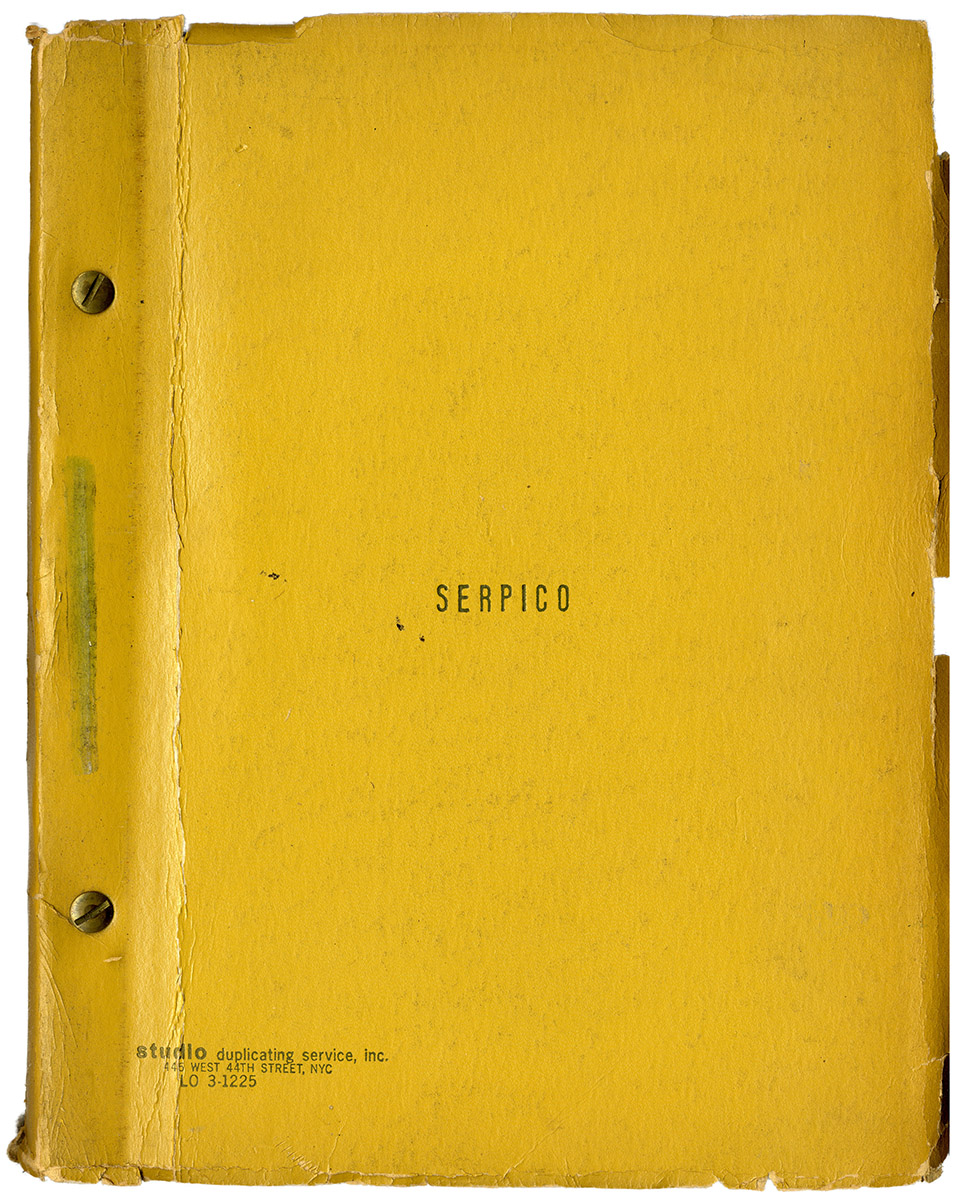

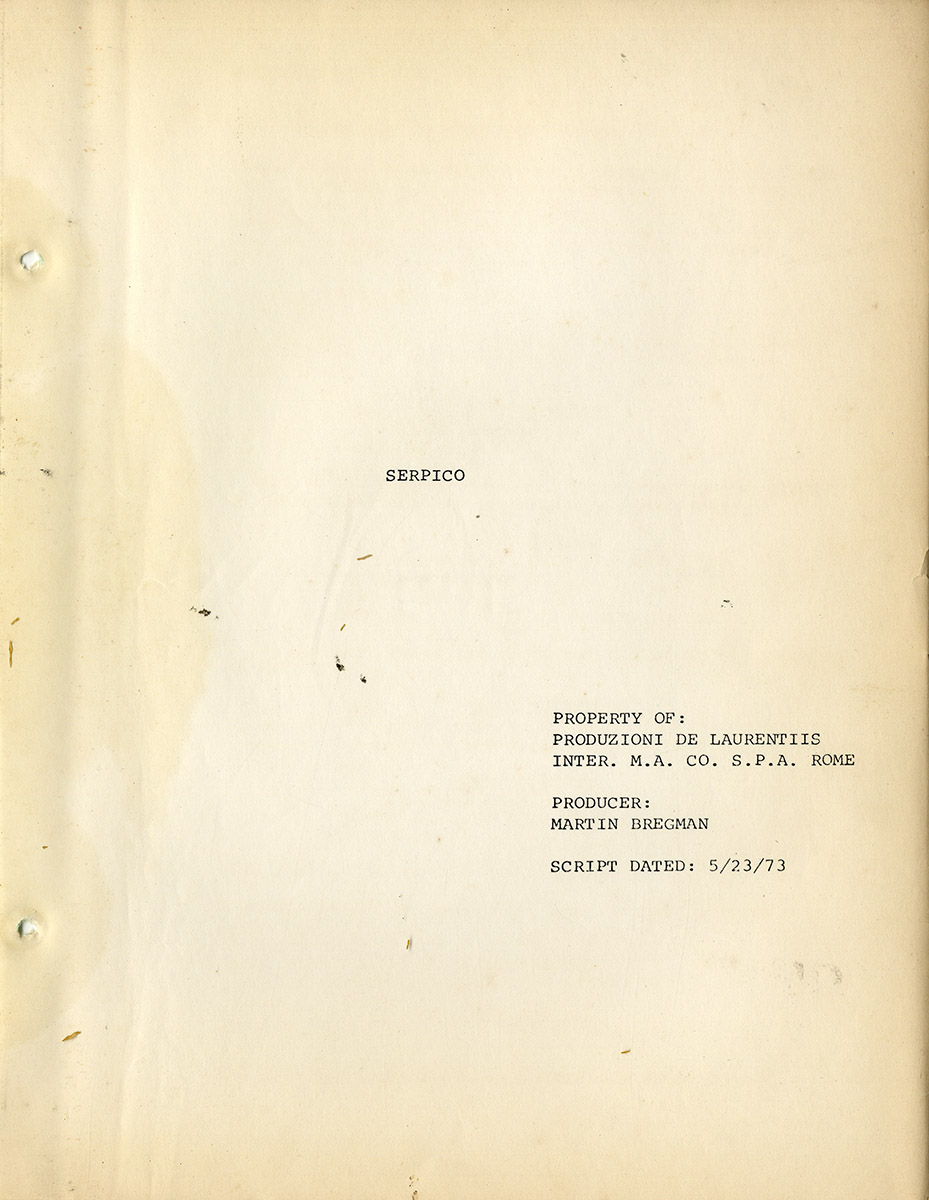

New York: Produzioni De Laurentiis, 1973. Vintage original film script, 11 x 8 1/2″ (28 x 22 cm.), 128 pp. Dated 5/23/73 on page 1 of script. Leatherette Studio Duplicating Service wrappers, bound into a spring binding with hair stylist Phil Leto’s name conspicuously stamped on front wrapper. Mimeograph (with only the title page some kind of vintage xerography), chipping to extremities of wrappers, script has been bound inside a blank set of wrappers, which in turn are attached with masking tape to the spring binding (which shows light signs of handling at extremities). Various pages have underlinings and small notes in Leto’s hand. Overall near fine in very good wrappers and binding.

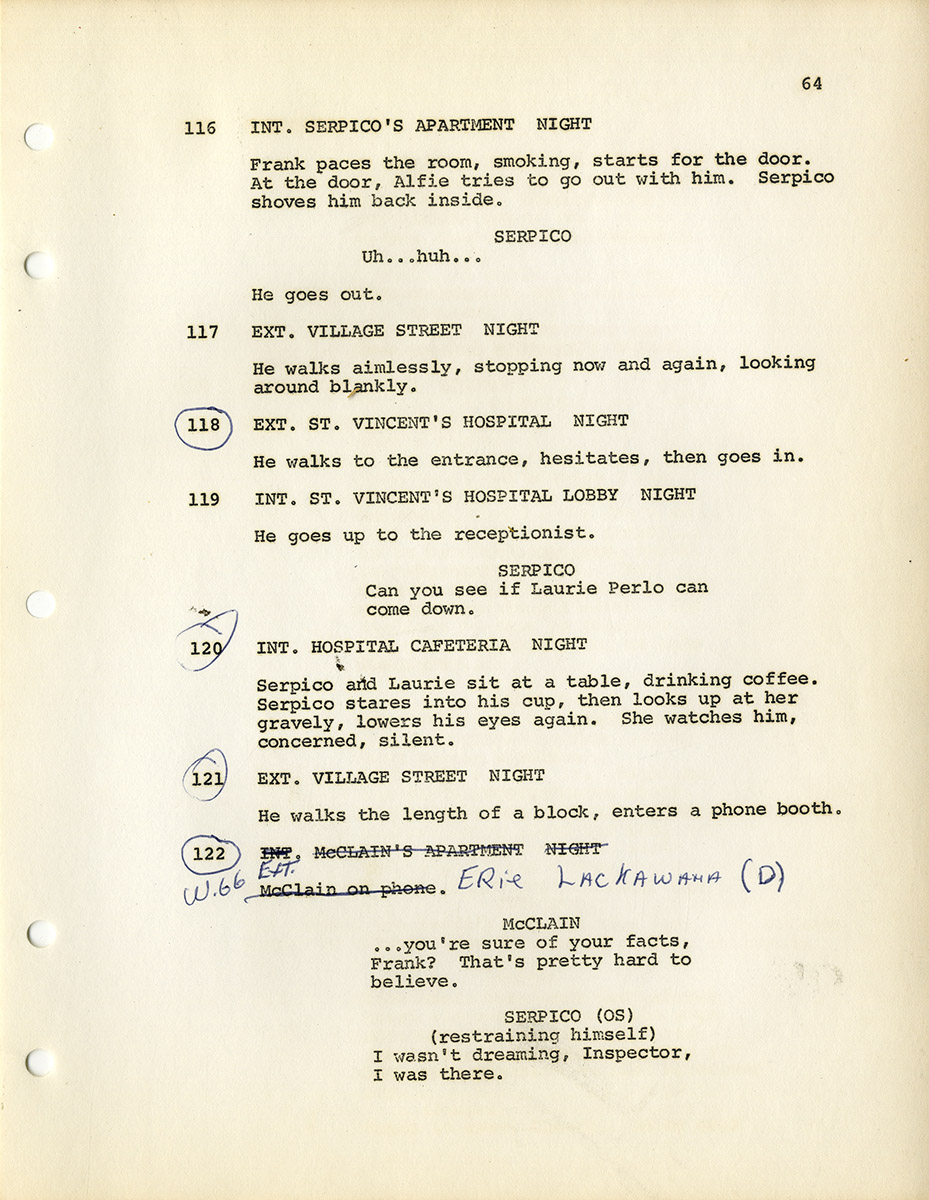

This copy belonged to Philip Leto, credited on film as hair stylist, and has occasional handwritten annotations by him indicating changes of shooting location. Leto’s contribution to the project was, in fact, significant, since Pacino’s evolving hair, mustache and beard style turned out to be one of the movie’s most noticeable elements.

Serpico was the first film produced by Al Pacino’s agent and personal manager, Martin Bregman, after securing Pacino his first lead role in The Panic in Needle Park (Jerry Schatzberg, 1971). Following the critical and box office success of Serpico, Bregman would go on to produce a series of acclaimed movies starring Pacino, including Dog Day Afternoon, Scarface, Sea of Love, and Carlito’s Way, as well as films with other stars.

Serpico was based on the bestselling biography of New York police officer Frank Serpico, written by Peter Maas. To adapt the book, Bregman and executive producer Dino De Laurentiis hired director John G. Avildsen (who would later direct Rocky) and veteran (formerly blacklisted) screenwriter Waldo Salt (Midnight Cowboy, Coming Home). However, Avildsen was not satisfied with Salt’s work and insisted that it be rewritten by screenwriter Norman Wexler, with whom he had previously collaborated on the sleeper hit Joe (1970). Serpico’s final screenplay, nominated for an Academy Award and winner of the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, is credited to both Norman Wexler and Waldo Salt.

Disagreements with producer Bregman led to director Avildsen being replaced by Sidney Lumet (12 Angry Men, The Pawnbroker), who turned out to be the perfect man for the job. Lumet was not only a master of New York location shooting, but also extremely skilled at working with improvisational method actors like Pacino. Moreover, Lumet had a genuine affinity for the film’s subject matter — systemic police corruption — and would return to it in at least three subsequent features: Prince of the City, Q & A, and Night Falls on Manhattan.

Serpico‘s May 23, 1973, screenplay, most likely a shooting script, is fairly close to what was actually filmed. The movie, in some cases — as in the opening sequence which intercuts a wounded Serpico being brought to the hospital with a flashback to his graduation from the police academy — follows the screenplay almost shot for shot. Lumet will sometimes remove dialogue in sequences where the images speak for themselves. Other sequences were eliminated, trimmed, replaced, or their order rearranged. Sequences involving Serpico’s first girlfriend were completely cut, but the sheepdog puppy she buys him, named Alfie, remains a significant character — in the movie, Serpico buys the little dog himself — and is seen growing older throughout the entire film. Serpico’s increasing alienation from the rest of the police department and its corrupt practices is shown through his change of residence — from the old neighborhood to Greenwich Village — and his evolving physical appearance, first a mustache, later, long hair and a beard, working in plain clothes, dressed like a hippie or a street person. Most of the changes from script to screen are reflective of director Lumet’s working methods, the authenticity of the locations and the extras who populate them, the insertion of naturalistic behavioral details, and the way he lets Pacino and the other actors improvise around the lines of the script.

Films like Serpico and The French Connection (1971) marked a change in American cinema, a new frankness and realism, reliance on location shooting, and an anti-establishment attitude that came to be known as the American New Wave. Like The French Connection, Serpico has its share of chases and action sequences — one sequence scripted as a brief pursuit and capture is elaborated by the moviemakers into a full-blown car chase with Serpico’s partner speeding their car down a busy city street in reverse. The film does not shy away from racial issues. Many of the suspects pursued and brutalized by the police are black.

As Frank Serpico moves from division to division he keeps encountering the same problem: cops who take regular bribes and expect him to do the same, “Who can trust a cop who won’t take money?” His repeated attempts to report the pervasive corruption to his superiors, up to and including the Commissioner and the Mayor’s office, are futile, resulting in a pat or two on the back for being an honest cop, but no real investigation — “Nothing about the brass, the bosses, how corruption like that could exist without anybody knowing.”

Eventually, with the help of a couple other men in the department he has learned to trust, Serpico takes his story to The New York Times and, as happened in real life, this leads to the formation of the Knapp Commission. But it’s a qualified happy ending. Soon thereafter, while making a narcotics bust with some other policemen (providing only indifferent support), Serpico gets shot in the face. Leading us back to where the story begins.

Serpico proved to be a triumph for everyone concerned, particularly director Lumet and star Pacino. Between the two of them, the writers Waldo Salt and Norman Wexler created a screenplay that plays as well as it reads.

Out of stock

Related products

-

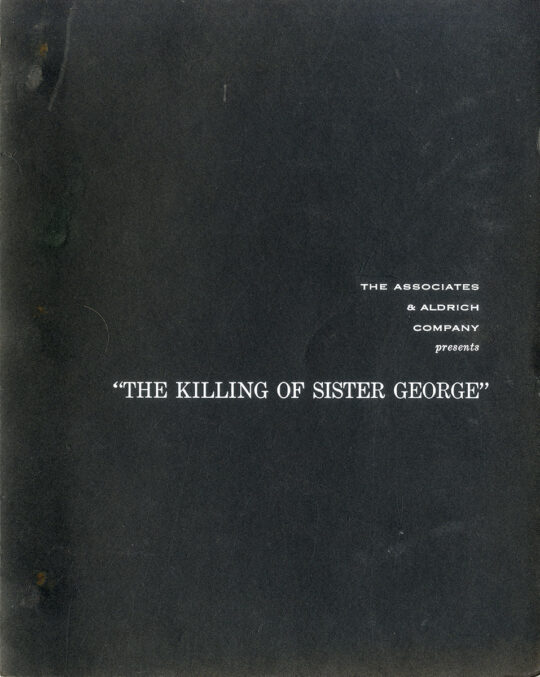

KILLING OF SISTER GEORGE, THE (1968) Film script

$3,000.00 Add to cart -

![[Doyle, Arthur Conan (source work)]: "SHERLOCK HOLMES FIGHTS BACK" [released as: SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SECRET WEAPON] 22 May - 17 June 1942](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/SherlockHolmesFightsBack-Script1-540x724.jpg)

SHERLOCK HOLMES FIGHTS BACK [released as SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SECRET WEAPON] (May 22-Jun 17, 1942) Screenplay

$2,000.00 Add to cart -

ALL THE YOUNG MEN (Sep 15, 1959) Revised Final Draft script by Hall Bartlett

$450.00 Add to cart -

CROSS CREEK (Feb 9, 1982) Rev Final Shooting script by Dalene Young

$750.00 Add to cart