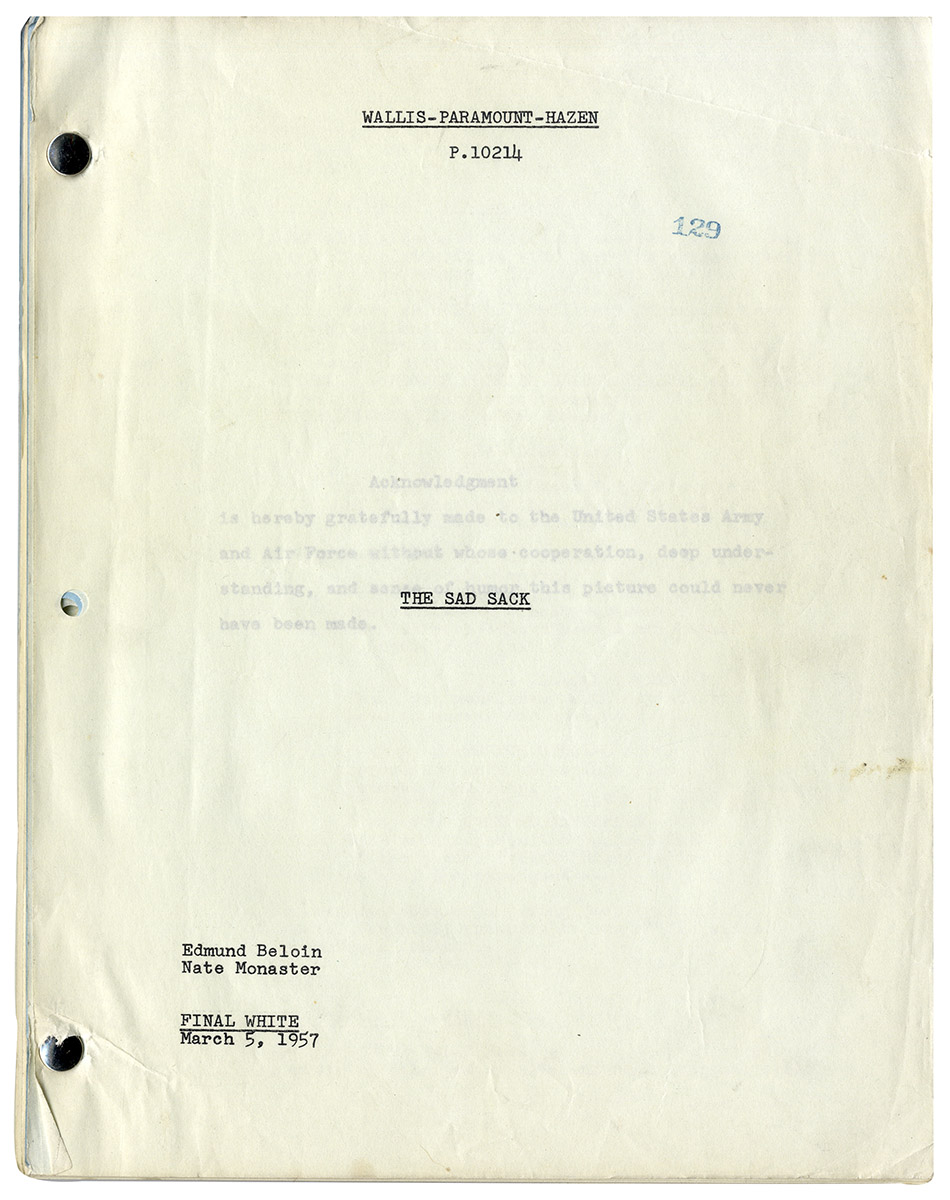

SAD SACK, THE (Mar 5, 1957) Final White script by Edmund Beloin and Nate Monaster

Hollywood: Paramount Pictures, 1957. Vintage original film script, quarto, brad bound, mimeograph, 133 pp., Title page denotes this as a FINAL WHITE and is dated March 5, 1957, with blue pages dated 3/12/57. Self-wrappers, 133 pp., near fine or better. With a six-page shooting schedule and a two-page call sheet laid-in.

THE SAD SACK was the second solo film made by comedian Jerry Lewis after the breakup of the phenomenally popular Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis comedy team. The screenplay by Edmund Beloin and Nate Monaster was specifically written for the Martin & Lewis team, however, in the completed film the part written for Martin is played by David Wayne.

THE SAD SACK’s director George Marshall (1891-1975) had a six-decade Hollywood career, starting in 1915 and ending in the mid-1970s. His best known movies are the Western, DESTRY RIDES AGAIN (1939), the film noir, THE BLUE DAHLIA (1946), and the Cinerama spectacular, HOW THE WEST WAS WON (1962). No stranger to comedy, Marshall directed two of the finest Laurel & Hardy shorts, THEIR FIRST MISTAKE and TOWED IN A HOLE (both 1932), as well as half a dozen Bob Hope vehicles, including THE GHOST BREAKERS (1940) and MONSIEUR BEAUCAIRE (1946). Working with producer Hal Wallis, he directed Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis in their first feature appearance, MY FRIEND IRMA (1949), and in their only 3-D film, MONEY FROM HOME (1954).

Screenwriter Edmund Beloin was also a comedy veteran, whose screen credits included THE HARVEY GIRLS (1946), A CONNECTICUT YANKEE IN KING ARTHUR’S COURT (1948), and three Paramount/Bob Hope vehicles MY FAVORITE BRUNETTE (1947), THE LEMON DROP KID, and MY FAVORITE SPY (both 1951). Beloin’s co-scripter on THE SAD SACK, Nate Monaster, had a background in radio comedy, and went on to write the Academy Award-nominated screenplays for PILLOW TALK (1959), LOVER COME BACK (1961), and THAT TOUCH OF MINK (1962).

THE SAD SACK’s screenplay was based on the hapless soldier character created during World War II by cartoonist, Sgt. George Baker. Baker’s Sad Sack debuted in a serviceman’s magazine in 1942, became a syndicated comic strip from 1948 through 1956, and then the lead character in a series of Harvey Comic books published from 1949 through 1982. Baker’s original serviceman’s strips were all in pantomime, with the character never speaking a word until his newspaper syndication and comic book incarnations.

Baker’s comic character was significantly altered for purposes of this Jerry Lewis vehicle. Nameless in the strip, he is called Meredith Bixby in Beloin’s and Monaster’s screenplay. Whereas in the strip, the character was utterly inept, in the screenplay he is something of an idiot savant with a photographic memory that enable him to win a bar fight using his book-learned knowledge of judo, and the ability to assemble a complicated R-2 Rapid Fire Cannon based on his memorization of the written instructions. The latter ability makes him useful to the story’s bad guys, a group of Moroccan bandits, because Bixby is the only one in their part of the world who knows how to assemble the weapon whose parts they have stolen. Unlike the comic strip character, he is not at all sad or mopey, but consistently cheerful. The screenplay has none of the comic strip’s regular supporting characters.

Comparing the screenplay to the completed film, there is almost no rewriting of individual scenes. However, there was some major narrative restructuring. The screenplay begins with Bixby and his two soldier buddies, Dolan (David Wayne) and Wenaslavsky (Joe Mantell), being awarded medals for their heroics in North Africa. This leads to a flashback introducing us to Dolan’s love interest, Major Shelton (Phyllis Kirk), a trained psychologist who wants to initiate a program that would help “congenital inferiors’ ‘ like Lewis’s Bixby to fit in. We then cut to the scene where Bixby meets his soldier buddies for the first time aboard a train. The movie eliminates the unnecessary flashback structure, and begins immediately with the scene aboard the train. The medal-awarding scene is moved to the movie’s conclusion where it chronologically belongs. Reading the screenplay gives one an appreciation of all the physical bits of business and verbal tics that Lewis added during the course of shooting.

Regardless, most of the film’s physical comedy is written in the script. That includes the movie’s funniest sequence where the Moroccan bad guys have Bixby and his two buddies chained up together in a tent. The screenplay describes it as “sort of a Chinese puzzle sequence, in which the bodies of the trio become more and more entwined.” Bixby is trying to reach the key to the chains’ padlock with his teeth, but when he moves an arm or a leg, he winds up moving the arm or leg of one of the other enchained prisoners until they figure out how to work together. This is the kind of body-contorting physical humor at which Lewis excelled.

The film is narrated in voiceover by the Dolan character, written for Dean Martin, but spoken in the movie by David Wayne.

DOLAN

(describing his first impression of Lewis’s character):

There he was — clear-eyed, pink-cheeked, open-faced. The boy next

door. The kind of man you’d want your sister to marry. The last guy in

the world you’d suspect of being the Kiss of Death.

Out of stock

Related products

-

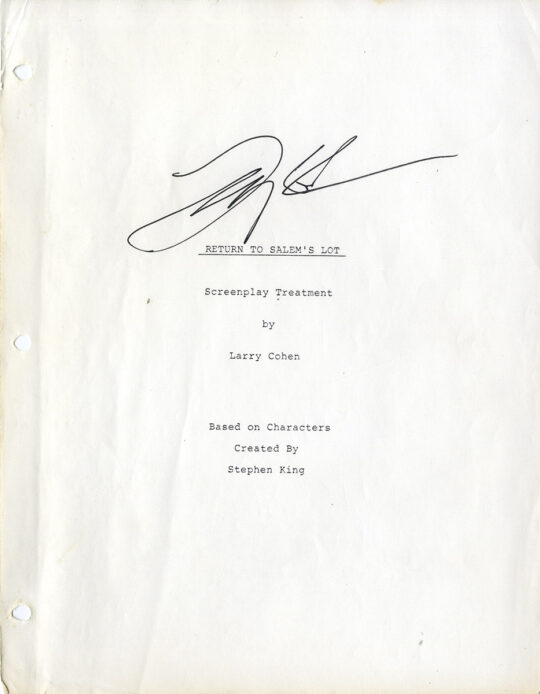

RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT, A (1987) Larry Cohen-signed archive

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

DRESS GRAY (Mar 6, 1981) Second revision script by Gore Vidal

$500.00 Add to cart -

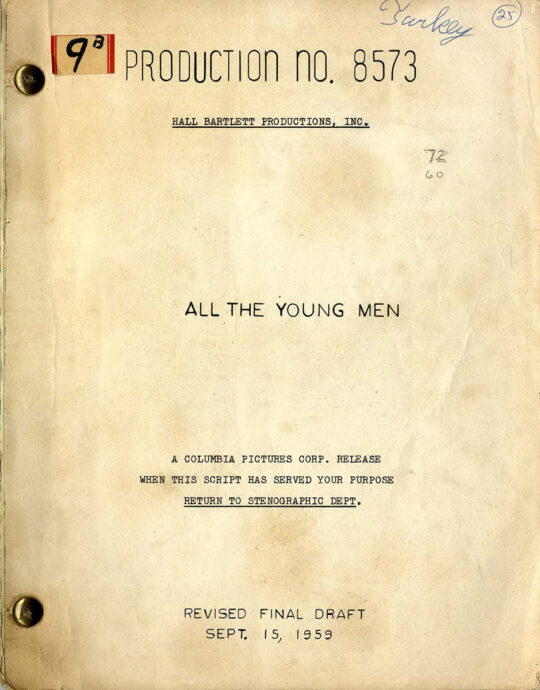

ALL THE YOUNG MEN (Sep 15, 1959) Revised Final Draft script by Hall Bartlett

$450.00 Add to cart -

![ESCAPADE [working title for: A WARM DECEMBER] (Jun 11, 1971) Revised First Draft screenplay](https://www.walterfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/EscapadeSCR_a-540x695.jpg)

ESCAPADE [working title for: A WARM DECEMBER] (Jun 11, 1971) Revised First Draft screenplay

$500.00 Add to cart