Three Legendary African American Female Vocalists

Mahalia Jackson, Marian Anderson, and Odetta are three legendary female vocalists who established the African American woman in the first half of the 20th Century as, not only a significant voice in the Civil Rights Movement, but a defining inspiration for both female and male vocalists.

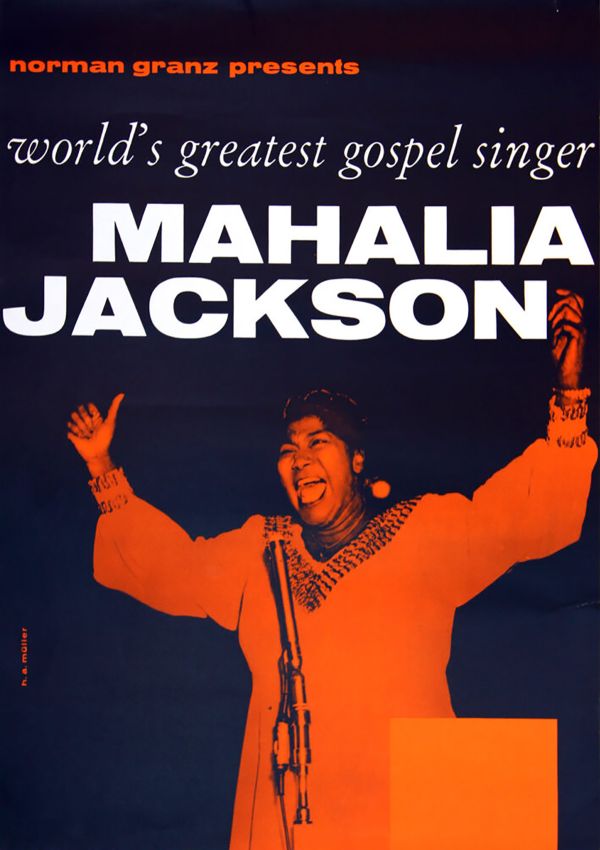

Above Image: Norman Granz, [ca. 1960] Vintage original 33 3/4 x 24″ (86 x 61 cm.), unfolded, uncut German printer’s proof poster, a few minor tears on left mended on back with archival paper, VERY GOOD or better.

Mahalia Jackson

Mahalia Jackson (October 26, 1911 – January 27, 1972) was an American gospel singer, widely considered one of the most influential vocalists of the 20th century. With a career spanning 40 years, Jackson was integral to the development and spread of gospel blues in black churches throughout the U.S. During a time when racial segregation was pervasive in American society, she met considerable and unexpected success in a recording career, selling an estimated 22 million records and performing in front of integrated and secular audiences in concert halls around the world.

The granddaughter of slaves, Jackson was born and raised in poverty in New Orleans. She found a home in her church, leading to a lifelong dedication and singular purpose to deliver God’s word through song. She moved to Chicago as an adolescent and joined the Johnson Singers, one of the earliest gospel groups. Jackson was heavily influenced by blues singer Bessie Smith, adapting her style to traditional Protestant hymns and contemporary songs. After making an impression in Chicago churches, she was hired to sing at funerals, political rallies, and revivals. For 15 years she functioned as what she termed a “fish and bread singer”, working odd jobs between performances to make a living.

Nationwide recognition came for Jackson in 1947 with the release of “Move On Up a Little Higher“, selling two million copies and hitting the number two spot on Billboard charts, both firsts for gospel music. Jackson’s recordings captured the attention of jazz fans in the U.S. and France, and she became the first gospel recording artist to tour Europe. She regularly appeared on television and radio, and performed for many presidents and heads of state, including singing the national anthem at John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Ball in 1961. Motivated by her experiences living and touring in the South and integrating a Chicago neighborhood, she participated in the civil rights movement, singing for fundraisers and at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. She was a vocal and loyal supporter of Martin Luther King, Jr. and a personal friend of his family.

Throughout her career Jackson faced intense pressure to record secular music, but turned down high paying opportunities to concentrate on gospel. Completely self-taught, Jackson had a keen sense of instinct for music, her delivery marked by extensive improvisation with melody and rhythm. She was renowned for her powerful contralto voice, range, an enormous stage presence, and her ability to relate to her audiences, conveying and evoking intense emotion during performances. Passionate and at times frenetic, she wept and demonstrated physical expressions of joy while singing.

Her success brought about international interest in gospel music, initiating the “Golden Age of Gospel” making it possible for many soloists and vocal groups to tour and record. Popular music as a whole felt her influence and she is credited with inspiring rhythm and blues, soul, and rock and roll singing styles.

In January 1972, she received surgery to remove a bowel obstruction and died in recovery. At her funeral service fifty thousand people paid their respects, many of them lining up in the snow the night before, and her peers in gospel singing performed in her memory the next morning. The day after, Mayor Richard Daley and other politicians and celebrities gave their eulogies at the Arie Crown Theater with 6,000 in attendance. Her body was returned to New Orleans where she lay in state at Rivergate Auditorium under a military and police guard, and 60,000 people viewed her casket.

–– Wikipedia

Marian Anderson

Marian Anderson (February 27, 1897 – April 8, 1993) was an American contralto. She performed a wide range of music, from opera to spirituals. Anderson performed with renowned orchestras in major concert and recital venues throughout the United States and Europe between 1925 and 1965.

Anderson was an important figure in the struggle for African-American artists to overcome racial prejudice in the United States during the mid-twentieth century. In 1939 during the era of racial segregation, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) refused to allow Anderson to sing to an integrated audience in Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. The incident placed Anderson in the spotlight of the international community on a level unusual for a classical musician. With the aid of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Anderson performed a critically acclaimed open-air concert on Easter Sunday, April 9, 1939, on steps of the Lincoln Memorial. She sang before an integrated crowd of more than 75,000 people and a radio audience in the millions.

During World War II and the Korean War, Anderson entertained troops in hospitals and at bases. In 1943, she sang at the Constitution Hall, having been invited by the DAR to perform before an integrated audience as part of a benefit for the American Red Cross. Her comment was, “I felt no different than I had in other halls. It was a beautiful concert hall and I was very happy to sing there.”

On June 15, 1953, Anderson headlined The Ford 50th Anniversary Show, which was broadcast live from New York City on both NBC and CBS. Midway through the program, she sang “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” and returned to close the program with her rendition of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” The program attracted an audience of 60 million viewers. Forty years after the broadcast, television critic Tom Shales recalled the broadcast as both “a landmark in television” and “a milestone in the cultural life of the ’50s”.

On January 7, 1955, Anderson became the first African-American to perform at the Metropolitan Opera. In addition, she worked as a delegate to the United Nations Human Rights Committee and as a Goodwill Ambassador for the United States Department of State, giving concerts all over the world. She participated in the civil rights movement in the 1960s, singing at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. The recipient of numerous awards and honors, Anderson was awarded the first Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963, the Congressional Gold Medal in 1977, the Kennedy Center Honors in 1978, the National Medal of Arts in 1986, and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991.

In 1992, after the death of Orpheus Fisher, her husband of 43 Years, she moved from their 100 acre farm in Danbury, Connecticut to the home of her nephew, conductor James DePreist, in Portland, Oregon. She died there on April 8, 1993, of congestive heart failure, at age 96.

–– Wikipedia

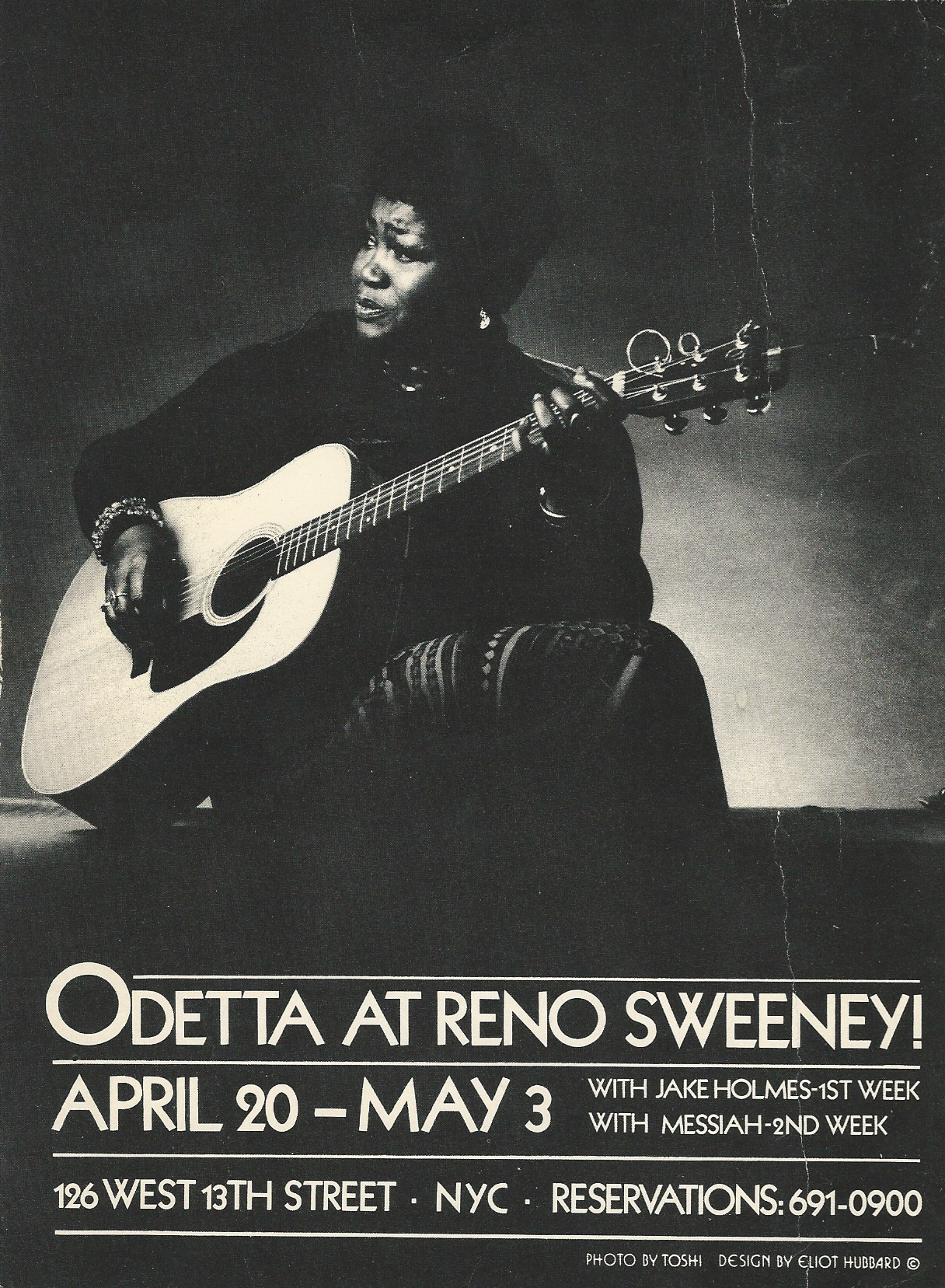

Odetta

Odetta Holmes (December 31, 1930 – December 2, 2008), known as Odetta, was an American singer, actress, guitarist, lyricist, and a civil and human rights activist, often referred to as “The Voice of the Civil Rights Movement”.

Her musical repertoire consisted largely of American folk music, blues, jazz, and spirituals. An important figure in the American folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s, she influenced many of the key figures of the folk-revival of that time, including Bob Dylan, who said, “The first thing that turned me on to folk singing was Odetta. I heard a record of hers Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues in a record store. Right then and there, I went out and traded my electric guitar and amplifier for an acoustical guitar, a flat-top Gibson. Joan Baez commented, “Odetta was a goddess. Her passion moved me. I learned everything she sang.” Janis Joplin who “spent much of her adolescence listening to Odetta, who was also the first person Janis imitated when she started singing.” The poet Maya Angelou, said, “If only one could be sure that every 50 years a voice and a soul like Odetta’s would come along, the centuries would pass so quickly and painlessly we would hardly recognize time.” Time magazine included her recording of “Take This Hammer” on its list of the 100 Greatest Popular Songs, stating that “Rosa Parks was her No. 1 fan, and Martin Luther King Jr. called her the queen of American folk music.”

On September 29, 1999, President Bill Clinton presented Odetta with the National Endowment for the Arts’ National Medal of Arts. In 2004, Odetta was honored at the Kennedy Center with the “Visionary Award”. In 2005, the Library of Congress honored her with its “Living Legend Award”.

In summer 2008, at the age of 77, she launched a North American tour, where she sang from a wheelchair. In November 2008, Odetta’s health began to decline and she began receiving treatment at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York. She had hoped to perform at Barack Obama’s inauguration on January 20, 2009, but she died of heart disease on December 2, 2008, in New York City, 29 days before her 78th birthday.

–– Wikipedia

- African American Movie Memorabilia

- African Americana

- Black History

- Celebrating Women’s HistoryI Film

- Celebrity Photographs

- Current Exhibit

- Famous Female Vocalists

- Famous Hollywood Portrait Photographers

- Featured

- Film & Movie Star Photographs

- Film Noir

- Film Scripts

- Hollywood History

- Jazz Singers & Musicians

- LGBTQ Cultural History

- LGBTQ Theater History

- Lobby Cards

- Movie Memorabilia

- Movie Posters

- New York Book Fair

- Pressbooks

- Scene Stills

- Star Power

- Vintage Original Horror Film Photographs

- Vintage Original Movie Scripts & Books

- Vintage Original Publicity Photographs

- Vintage Original Studio Photographs

- WalterFilm